Despite the Basque language Euskara being so old, there are so many firsts related to the language that are not so old. The first translation of the Bible into Euskara occurred in 1571. The language itself was only standardized in the 1970s. Bizenta Mogel is another first. She is the first woman to write a book in Basque, in 1804. Only two years before, her uncle wrote the first novel in Basque. Though the language is old, so much of its history is relatively new. In comparison, the first book written by a woman in English is Revelations of Divine Love, written by Julian of Norwich around 1393, while the first known female author in any language was Enheduanna, a Mesopotamian woman who lived during the 23rd century BCE. Incidentally, she is the earliest named author in history.

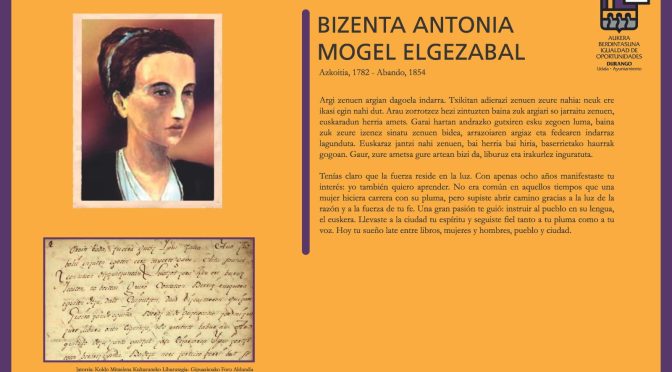

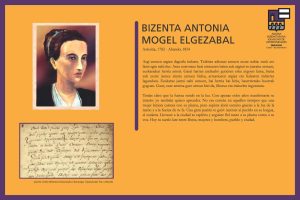

- Bizenta Antonia Mogel Elgezabal was born in 1782 in Azkoitia, Gipuzkoa, where her father practiced medicine. When she was still very young, her father died so she and her brother Juan José moved to Markina, in Bizkaia, to live with their uncle, Juan Antonio Mogel, who was a priest and a prominent writer. (In 1802, he wrote the first novel in Basque, Peru Abarca.) Their uncle saw to their education, which consisted of Latin, French, and Euskara, along with math and science. She thus received an education that was very uncommon for women of the time.

- For a long time, Bizenta was considered the first woman to write in Basque, though recently there is a question as to whether Estíbaliz Sasiola, whose compositions are included in the manuscript of Joan Pérez de Lazarraga of the 1500s, might make that claim. It isn’t clear if Sasiola actually wrote those verses or just compiled them. In any case, Bizenta is the first woman to write a complete book in Basque. She wrote during a time when most women were not literate and thus she was often “forced to give explanations about her status as a literate woman and writer.”

- Her best known book is Ipui Onak, or The Good Stories. Published in 1804 when Bizenta was only 22 years old, this book consists of translations of fifty of Aesop’s fables and another eight of her own uncle’s. The book was so popular that it was reprinted several times. As she said herself, her audience was children and the common folk, or peasants.

- Ipui Onak was also the first book of fables written in Basque. At the time, it was thought that all stories should have a moral, and Bizenta chose Aesop’s fables as they had strong morals, to replace the “bad stories” that the farmers and peasants told themselves just for fun.

- In 1817, she married Eugenio Basozabal, a successful merchant. Between 1819 and 1832, she wrote the Gabon Cantac (Christmas Songs). Some of those songs were signed anonymously as Emacume batec ateriac, 1819. Urtian Abandoco elexatian (“Published by a woman in 1819 in the church of Abando”).

- In addition to being a writer, she was also a translator and an advocate for women’s rights to education. She died in Abando in 1854 at the age of 72.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: López Gaseni, Manu. Mogel, Bizenta. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2024. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/mogel-bizenta/ar-96516/; Bizenta Mogel, letras contra los vientos y mareas de su época by Jon Mujica, Deia; Vicenta Moguel, Wikipedia; Bizenta Mogel, Wikipedia