Dad would have turned 79 today. I miss you, dad.

I’m often asked why I do this. Why did I start this website? Why do I invest so much time in it? Why is the Basque thing so important to me? For a long time, I didn’t really have a good answer. Maybe because it’s cool? I mean, being Basque is sort of like being part of a special club. A mysterious origin lost to the mists of time. A strange and unique language that even the devil struggled to learn. Long and unprounouncable last names that are full of k’s and tx’s. A people who have been besieged from all sides but somehow managed to maintain their identity over the centuries. Isn’t all of that cool?

As I dwelled upon it more over the years, though, I realized that wasn’t the real reason I created this page and continue to maintain it. The real reason was my dad.

I can’t claim that I was overly close to my dad. When I was a kid, we never played catch or kicked a ball. We never talked about girls – he never had any advice for me regarding romance. We never hung out, just the two of us. We never talked about my future, about what I wanted to be when I grew up. I don’t think dad ever really appreciated what going to graduate school and studying physics really meant, where it might lead me. He was just a little flabbergasted that anyone would choose to go to school that long. And the only real advice he ever gave me was to work inside, with an air conditioner, not outside in the hot sun like a jackass like he did.

When we were kids, my brothers and I would often go out with dad on his hay runs. He would get one of us up at some ungodly hour – sometimes as early as 3 or 4 in the morning – since he wanted to be at the haystack by dawn to begin loading the truck. I didn’t like getting up that early, but it was one of the few times it was just me and dad. It was the only time we got to sort of hang out together. We didn’t talk much, but we would stop at some convenience store, grab a few sodas and sandwiches. At the haystack, I would help straighten loose bails or tie up the ropes when he was done. It wasn’t much, but it was time, just me and dad.

It took me a while to understand that there was this gulf between me and my dad that was almost insurmountable. We came from different cultures, from different worlds. Growing up in the United States, I was part of a collective experience with my friends and neighbors. We all studied the American Revolution and the Civil War in school. We all knew the rules to football and baseball. We all got excited about the next episode of Knight Rider or The Greatest American Hero (ok, maybe that was just me). But, my dad didn’t have any of that. He couldn’t care less about American football. His sport was boxing. And while he did get into some TV shows – Little House on the Praire or Walker, Texas Ranger – these weren’t the exciting new shows that me and my friends watched. And he didn’t really know much about US history.

And what he did know – Euskara, the folksongs of Bizkaia, the history of Goikoetxebarri, the baserri he was born in – he never really shared and so it was foreign to me. When I was a kid, dad worked and tended his garden – he didn’t really have any hobbies. When I was older, after I left for college, dad started making jamón and chorizos – things that came from his upbringing – but by then I was off doing my own thing and I never really got to learn how to do those things from him.

My dad came from a very different cultural context, one that I knew next to nothing about. In the first thirty years he lived in the United States, he went back to the Basque Country maybe twice. And he couldn’t afford to take us.

When I was in college, studying physics at the University of Idaho, I decided to go to the Basque Country myself and learn Euskara. My dad asked me why. Why learn Euskara? Spanish was so much more useful, you could speak it in so many more places. I tried to explain that I wanted to learn Euskara because it was his language, that I wanted to learn more about his culture. I think he understood, but if he did, he never really said so. But, even more than learning some of his language and culture, I got to meet his family, I got to meet the aunts and uncles I never knew, I even got to meet my amuma for the first time. I stayed in the baserri – Goikoetxebarri – where he grew up. I started getting to know something about where dad came from.

After I got back and started grad school at the University of Washington, I decided what I had learned about the Basque language, culture, and people was cool, and I wanted to share it, so I created this page. I quickly made a lot of new friends, people in the Basque Country who were eager to share their culture with the rest of the world. And it was a way for me to build even stronger connections to the Basque Country, to learn something beyond the things I could read in the admittedly few books I could find in English, most of which focused on history or the pastoral life of the Basque sheepherder in America. None of those books talked about the Basque Country as it is today. I learned about bands like Negu Gorriak and Su Ta Gar. I learned about the unique policies of Athletic Bilbao. I saw the Guggenheim. I learned about the complex political history of the Basques. And I learned about the land my dad came from.

Ironically, I learned about a Basque Country that my dad didn’t really know. Much had changed in the decades since he left the Basque Country. The music was different. The language itself was different. While the baserri was still an important part of Basque cultural identity, the direct connections to it were different, more remote. Just as many baserri had become luxury dwellings as they were the ancient centers of family that my dad grew up in. Once, when we were all driving somewhere in dad’s big pickup truck, I had him pop in a cassette of Negu Gorriak. Normally, he just ignored the loud noise that I played from the speakers, but this time, he understood some of the lyrics. And it was the first time he said something like “What the hell is this?”

Even though the Basque Country I got to know had changed a lot from the Basque Country my dad grew up in, it still gave me a touch stone. More importantly, I got to know some of the names of the people he grew up with. The names of the other baserriak and barrios. I slowly began to recognize the names and places he would throw out in the stories he started telling. And when I took him to the Basque Country, just him and me, I was able to start putting things together.

Back in 1997, my dad had a heart transplant. We were lucky that Washington has a great med school and I was living in Seattle, getting my PhD, so mom and dad could live with me for a time. And, after dad’s surgery, he still had to come back up for appointments, and he would crash with me. I didn’t really take advantage of having dad around as much as I should have, but I was still able to spend time with him, often in the kitchen, as he started cooking more and hanging out with some of the Basque friends I had made. We weren’t playing catch or anything like that, but we finally got some time to just hang out.

On one drive, up from Nevada back to Idaho, I got my dad (at the suggestion of my wife Lisa) to start talking about his childhood. And I recorded it. He would throw out names of people, baserri, and towns as if I should know them all, and I was pleasantly surprised that I did know at least some of them. I knew who this lady was, or where that town was. A lot of names still escaped me, but I knew a lot more than I would have guessed. And I could ask him questions about these people and places, at least some of them, because I knew who and what they were.

In the end, this page and all of the things I’ve learned over the years working on it, all of the people I’ve gotten to know through it, all gave me some connection to my dad that I would never have had otherwise. I like to pretend that I got to know him a little better by getting to know the Basque Country, that maybe I understand a little more where he came from and the circumstances and culture that made him the man I knew. This page is my way of honoring my dad and keeping him alive.

So, yeah, it’s cool to be Basque, but it’s even cooler getting to know my dad better.

Goian bego, aita. I miss you.

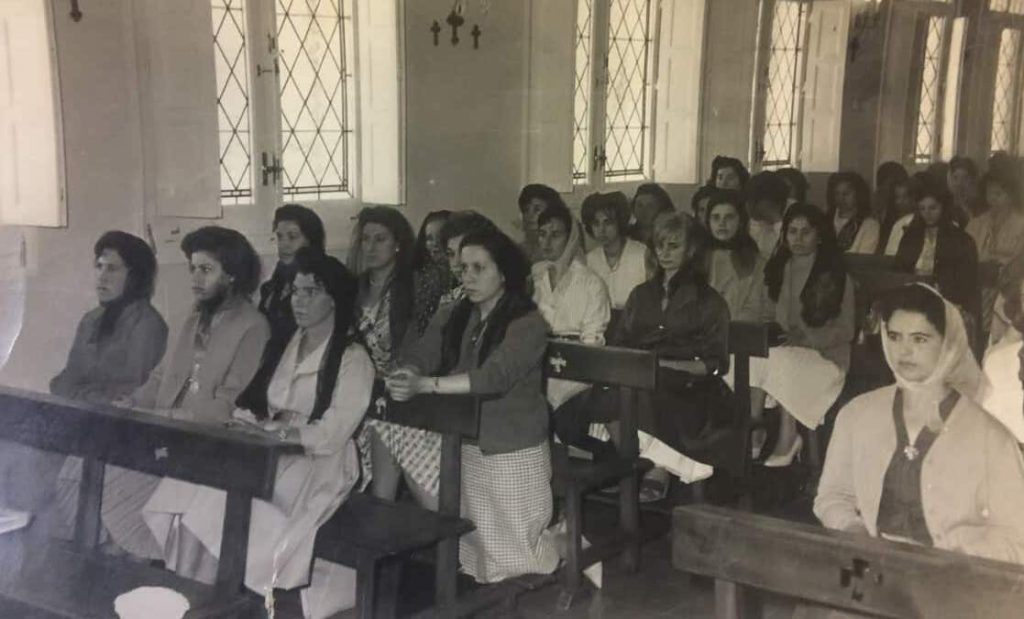

Thanks to Lisa Van De Graaff for encouraging me to record dad and his stories when I could. Lisa took the photo at the top.