The Basque Witch Trials epitomized a time of hysteria and violence. Inspired to some degree by the neighboring trials in France, almost 7,000 people were investigated by the Spanish Inquisition on suspicions of being witches or dealing in witchcraft. While not so many were executed, by European standards, the wealth and breadth of records associated with the trials on both sides of the border have been a trove for historians. Past works, such as The Witches’ Advocate by Gustav Henningsen, have focused on the beliefs of the accusers, trying to understand what they really believed about witches, with implications about what the Church believe about witches at the time.

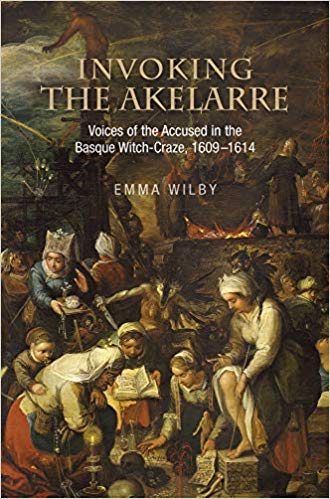

Emma Wilby’s Invoking the Akelarre: Voices of the Accused in the Basque Witch-Craze, 1609-1614 takes the opposite approach. As the subtitle indicates, Wilby scours the records, the testimonies that have been preserved in various archives, to understand the world that the victims of the witch craze came from. What did they believe? What in their world led them to construct the fantastical stories they told their interrogators?

Wilby’s basic premise is that the beliefs of the victims lies buried within their testimony. While clearly some of what they told their interrogators was the result of leading questions and the interrogators’ own biases, and other parts came from some of the resulting hysteria that arose around the trials, much of what came through in their stories was based on their daily experience, their unique world views that the interrogators couldn’t have known much, if anything, about. She further tries to identify those elements that made the Basque witch trials unique compared to the rest of Europe. In doing so, she reveals a rich world in which the beliefs of the every day Basque peek through, a world that is, often, very foreign to us today. While Wilby admits that many of her conclusions are necessarily speculative, given the indirect window the testimonies we have offer to the lives of those Basques, she supports them with as much circumstantial evidence, both from the Basque Country and the rest of Europe, as she can to make a convincing case.

There are simply too many tidbits that I found fascinating to summarize here. However, here are a few that I particularly found intriguing.

- We all know that the Basques have a relatively high frequency of Rh negative blood type. This can cause issues with fertility, leading to a relatively high rate of miscarriage, stillbirth, and death soon after birth. Wilby relates this to both the Basques perhaps unique perspective on young children (saying that Basques, and Europeans more generally, didn’t really view children as something to emotionally invest in until they were a few years old) and that this is one reason the Basque population remained relatively small and isolated during history.

- She relates many of the activities associated with witches, particularly the stories of using parts of the dead in rituals and medicines and sucking blood from people, to the activities of women as healers and herbalists. Bloodletting was a common treatment at the time and victims may have conflated experience in trying to heal people with common medical practices. They often made special medicines, such as pain killers, out of animals and herbs that may have inspired other stories.

- The descriptions of the Sabbath, in which witches feasted and held orgiastic celebrations, may have found some inspirations in the stories of Cockaigne, a mythical paradise where people could do anything they wanted, and where, for example, “candies and pastries would rain from the sky.” They may have also been inspired by confraternities, religious and secular groups that acted as some level of social safety net but also held celebrations for their members. Finally, Basque theater, with raucous descriptions of the Devil, may have also provided further inspiration.

- Basques had a unique relationship with the Americas, with many men having gone away, leaving the women behind to deal with all aspects of domestic life. Upon their return, the men often had fantastic tales of American natives and their, for the Basques, bizarre religious festivals that often contained stories of cannibalism, that may have made their way into the stories that the victims of the Basque witch trials told their interrogators. Witches’ stories of cannibalism may also have been inspired by sometimes graphic descriptions of the transformation of the Eucharist to flesh and blood.

- Basques may have also had a relatively liberal view towards sex. Wilby quotes noted historian William Douglas: “in some of the medieval literature from western Europe, the Basques are described as sexually promiscuous.” And Pierre de Lancre, the interrogator on the French side, was shocked by the way that Basque peasants “try out” their wives “for several years before marrying them, taking them as if on a trial basis.” This liberal attitude towards sex may explain the very explicit descriptions of sexual activity that found their way into the stories of the Sabbath.

These are only some examples of how Wilby mines the testimonies of the victims to shed light into their world, their beliefs, and their relationship to their religion. Her approach is very academic, which may not be to everyone’s taste, but the insight she provides on who these Basques were is both striking and illuminating. Their world is so different than the one we have and it is almost impossible to imagine living in it. Wilby provide a glimpse that leaves you wanting more.

The hardcover is out now and available at numerous booksellers. The paperback version will be out in the summer of 2020.

Share this / Partekatu hau:

Like this:

Like Loading...