Not hosting my site on WordPress.com, I never noticed this fancy button that allows people to enter an email address to receive notices of posts to the blog. It wasn’t until I saw Hella Basque‘s follow button that I became aware of this feature. I found a plugin that allows and WordPress-driven site to have a similar feature. So, if you want to receive email notification whenever a new posting is made to Buber’s Basque Page, click the “follow” button at the bottom of the page.

Zorionak NABO!

This year marks the 40th anniversary of NABO — the North American Basque Organizations. NABO’s goal is to bring together the Basque clubs of North America (NABO has member clubs in Canada and the United States) to help those clubs in their efforts to preserve and promote Basque culture. NABO is thus a collection of organizations and is able to provide opportunities that individual clubs would not be able to, such as the national Mus tournament and the Udaleku summer camp.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of NABO — the North American Basque Organizations. NABO’s goal is to bring together the Basque clubs of North America (NABO has member clubs in Canada and the United States) to help those clubs in their efforts to preserve and promote Basque culture. NABO is thus a collection of organizations and is able to provide opportunities that individual clubs would not be able to, such as the national Mus tournament and the Udaleku summer camp.

I first encountered NABO about 14 years ago, via my involvement with the Seattle Euskal Etxea. At the time, Bob Echeverria was president. Grace Mainvil, who has been a constant presence within NABO, was treasurer. I remember being overwhelmed by all of the experience that was represented in that room and all of the great ideas that were being tossed around. As with any such organization, NABO had more ideas than it could realistically realize, but it was great simply seeing the energy of the people involved. I remember that there were ideas for a directory of Basques in the diaspora (a very ambitious idea that unfortunately didn’t go anywhere, partially because they tapped me to be involved and I, well, sort of dropped the ball…). I don’t remember many more specifics, but I simply remember being part of something big and grand.

More recently, I’ve been to a NABO meeting a few years back, in Salt Lake City, as president of the New Mexico Euskal Etxea. While some faces have changed (the current president is Valerie Arrechea), others are familiar (Grace is still treasurer), the energy and ideas were as vibrant as ever. One simply cannot forget the energy that John Ysursa brought with him, and the grand visions regarding Basque identity and building the desire for embracing that identity among young Basques in the diaspora.

Last week, NABO celebrated their 40th anniversary in Elko as part of the 50th anniversary of the Elko Basque festival. Unfortunately, I was not able to attend, but it sounds like, by all accounts, it was a grand weekend.

NABO offers a valuable presence in the Basque community by pooling together the resources and expertise of all of the individual clubs and providing a common voice that can help promote projects that are simply too big for any one club. It also offers a network for Basque clubs and their members that helps develop a national and international Basque identity, where Basques are exposed to other Basques from other parts of North America. Basques in California get to interact with those in Washington DC, Quebec, and Florida. This expands the concept of “Basqueness” in the diaspora, as each of these communities has a different history, from the sheepherder experience, to the jai alai players, to more distant roles in exploring and settling North America. By providing this umbrella, NABO expands and redefines what it means to be Basque.

Zorionak NABO! And here’s to another 40 great years!

Pre-Neolithic Genetics of the Basques

I’m not a geneticist, but I am fascinated by what modern genetics can tell us about the history and prehistory of humans. The Basques are particularly interesting because of the pre-Indo-European origins of the population. As more and more genetic studies are done, I think we will ultimately recreate a detailed map — both spatial and temporal — of the movements of not just the Basques but all human populations.

I’m not a geneticist, but I am fascinated by what modern genetics can tell us about the history and prehistory of humans. The Basques are particularly interesting because of the pre-Indo-European origins of the population. As more and more genetic studies are done, I think we will ultimately recreate a detailed map — both spatial and temporal — of the movements of not just the Basques but all human populations.

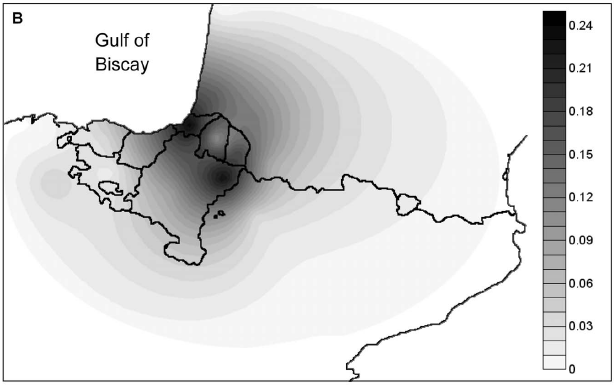

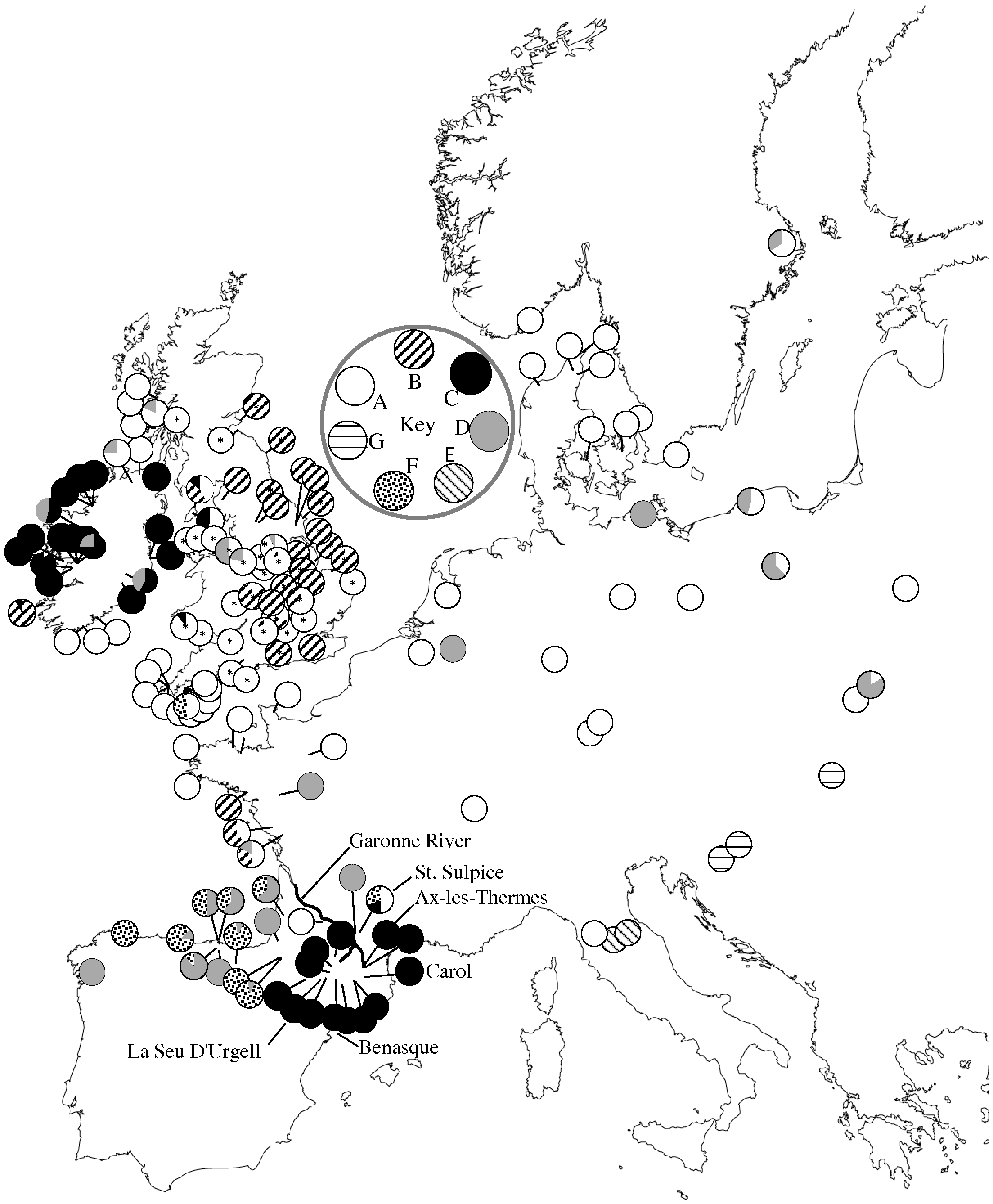

In a recent paper in PLOS One, a group of scientists from the Basque Country, Santander, and Florida examined mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from a group of people in “Franco-Cantabria” (which I assume is located in essentially modern day Euskal Herria). mtDNA is passed through females and tracing it provides data on the maternal ancestry of the people. The authors find that there is an unbroken genetic lineage back about 10,000 years to the local area. They conclude that their findings “provide robust evidence of a partial genetic continuity between contemporary autochthonous populations from the Franco-Cantabrian region, specifically the Basques, and Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherer groups” and “these results give further support to the notion that the autochthonous populations currently inhabiting this region show perceptible signals of genetic continuity with Mesolithic hunter-gatherer groups that took refuge in the Franco-Cantabrian fringe during the last glacial and postglacial periods of Europe.” That is, as far as I understand, the current Basque population is directly connected to the people who inhabited the region at the end of the last ice age.

There still seems to be a lot that is unknown and it is hard to parse all of this data if you aren’t a specialist. But, these genetic studies and what they say about human populations and migration are very intriguing. I’d welcome more informed discussion on this, both what these kinds of studies say about the origins of the Basque population as well as their interactions with the rest of Europe.

The destruction of San Sebastian, recreated via Twitter

- Today is July 10, 1813. Donostia has been occupied by Napoleonic troops for 5 years.

- The Marquess of Wellington, commander of the allied troops, reaches Hernani.

- The British have already landed troops and weapons and ships have begun the blockage. The siege of Donostia begins.

200 hundred years ago today, the Siege of Donostia began, which ended in the ransacking and devastation of the city by fire (see this Wikipedia article). This was part of a campaign, the Peninsular War (known in Spain as the Spanish War of Independence), lead by the British, to defeat Napoleon, who, upon taking over France, had named his brother King of Spain. The British forces, lead by the Marquess of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, had just won the Battle of Vitoria and marched on San Sebastian to both “clear their rear guard” and establish a port for supplying their forces. After about two months of siege, they finally took the city. Discovering all of the “brandy and wine” of the shops, many troops got drunk and attacked the civilian population, burning houses, killing people, and raping women.

200 hundred years ago today, the Siege of Donostia began, which ended in the ransacking and devastation of the city by fire (see this Wikipedia article). This was part of a campaign, the Peninsular War (known in Spain as the Spanish War of Independence), lead by the British, to defeat Napoleon, who, upon taking over France, had named his brother King of Spain. The British forces, lead by the Marquess of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, had just won the Battle of Vitoria and marched on San Sebastian to both “clear their rear guard” and establish a port for supplying their forces. After about two months of siege, they finally took the city. Discovering all of the “brandy and wine” of the shops, many troops got drunk and attacked the civilian population, burning houses, killing people, and raping women.

As an experiment in historical education, Euskomedia is recreating the Siege and Destruction of Donostia via Twitter. Two Twitter feeds, 1813tik in Euskara and 1813tik-es in Spanish, will relay the siege over the coming weeks to provide “real-time” updates on this historical event.

I think this is an awesome idea! It is a very cool way of using modern social media to educate people about history. It tries to capture the power of social media — the way it has been used in revolutions and uprisings in, for example, the Middle East — to recreate dynamic historical events of the past. I think this might be an excellent educational tool and I hope it catches on. The US just marked the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg — something like this would have been a cool way for people to be more directly engaged in that anniversary.

I only wish they had an English Twitter feed as well!

Regarding the weirdness (or non-weirdness) of Euskara

Yesterday I posted about another blog that ranked languages in terms of “weirdness”, which made the claim that Spanish, German and English were much weirder, in comparison with other languages, than Euskara. Well, another blog, this one from the Language Log at the University of Pennsylvania describes some issues with this analysis. In particular, a number of the comments on that blog delve into a lot of questions (as an aside, I am extremely envious of the 54 comments that posting has received! 🙂

They point to limitations of the WALS database, the fact that the analysis only used 21 factors in its weighting, and that defining weirdness is a bit arbitrary.

Just thought, for the sake of rigor, I should share this discussion.

Maybe Euskara isn’t so weird, maybe English is the weird one?

One of the people who follow Buber’s Basque Page on Facebook (thanks Rachel!) sent me this link to a blog post that evaluates the weirdness of languages. I’m not a linguist, so I can’t really comment on their methodology, but it seems that what they’ve done is compared all of the languages that are assessed in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS). What WALS does is classify languages based on a number of criteria, including the types of sounds (consonants vs vowels, types of consonants, etc), the number of genders, the types of articles, and how tenses are created (for a full list of the categories and how Basque fits, see this page). What Idibon did was compare all of the categorized languages in 21 of these categories and determine which ones deviated the most from the average and which ones did not.

One of the people who follow Buber’s Basque Page on Facebook (thanks Rachel!) sent me this link to a blog post that evaluates the weirdness of languages. I’m not a linguist, so I can’t really comment on their methodology, but it seems that what they’ve done is compared all of the languages that are assessed in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS). What WALS does is classify languages based on a number of criteria, including the types of sounds (consonants vs vowels, types of consonants, etc), the number of genders, the types of articles, and how tenses are created (for a full list of the categories and how Basque fits, see this page). What Idibon did was compare all of the categorized languages in 21 of these categories and determine which ones deviated the most from the average and which ones did not.

What is very surprising is that, in this measure, Basque is not at all that odd. It has properties that are very common across languages. It ranks in the top 10 of least weird languages. In contrast, languages like Spanish, Dutch, German, and English rank high in the weirdness index. It seems that some of the most spoken languages in the world are also some of the weirdest, in terms of their structural properties.

This is pretty surprising, to me at least. However, it does conform to the idea that Basque isn’t necessarily hard, it is just hard for an English speaker, because it is so different.

Hella Basque is Hella Blog

Writing a blog, putting posts out there on a regular basis, requires dedication. Writing a blog that pulls in readers and engages them requires charm and wit. Hella Basque has both. Billed as “youthful musings on Basque American culture and community,” Hella Basque is the work of Anne Marie, a young Basque-American who has been immersed into Basque-American culture for many years and is now pouring out those years into a blog that is both insightful and a delight to read. Hella Basque has posted about the band Amuma Says No, the Top 5 Things Not to Say to a Girl’s Aita (I will have to note these down for the very distant future when my little girl gets to that age), and You Know You’re Basque American When… (which has been shared many times on Facebook), among other topics.

Hella Basque has only been posting for a few weeks, but the writing and the choice of topics makes it a top choice among Basque blogs. I highly recommend it!

Big Basque News: Basque World Heritage Site and .eus Basque Internet Domain

Two big news items related to Basques this week.

First, long time contributor David Cox, who also happens to be Canadian (we don’t hold that against him), sent this article about the possibility of the Red Bay National Historic Site in Labrador becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Canadian Officials are currently lobbying UNESCO to make that site, and another in Canada, World Heritage Sites. Red Bay is home to a 16th century Basque outpost on the eastern coast of Canada. Drawn initially by cod, it seems, the Basque sailors found whales as well and setup the site to process the whales. The site has been excavated and a cemetery, a number of ships both large and small, and processing stations. The article points out that the establishment of this processing center in Canada marked the beginning of commercial whaling and that establishing it as a World Heritage Site would indicate “that the story of the Basque Whaling in Red Bay is a story that should be protected and presented for all humanity.” To get a feel for what it might have been like for Basques living in Labrador in the 1500s, check out the Last Will and Testament of Juan Martinez de Larrume.

First, long time contributor David Cox, who also happens to be Canadian (we don’t hold that against him), sent this article about the possibility of the Red Bay National Historic Site in Labrador becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Canadian Officials are currently lobbying UNESCO to make that site, and another in Canada, World Heritage Sites. Red Bay is home to a 16th century Basque outpost on the eastern coast of Canada. Drawn initially by cod, it seems, the Basque sailors found whales as well and setup the site to process the whales. The site has been excavated and a cemetery, a number of ships both large and small, and processing stations. The article points out that the establishment of this processing center in Canada marked the beginning of commercial whaling and that establishing it as a World Heritage Site would indicate “that the story of the Basque Whaling in Red Bay is a story that should be protected and presented for all humanity.” To get a feel for what it might have been like for Basques living in Labrador in the 1500s, check out the Last Will and Testament of Juan Martinez de Larrume.

Second, as some of you may now, there has been an effort for quite some time now to get a top-level domain (think .net, .com, .edu, .es) on the internet for things Basque. I’ve featured a link in the top right corner of my page to the group that is advancing this cause, The PuntuEus Foundation. A couple of weeks back, ICANN, the organization that decides these things, approved the creation of the .eus domain. Now, there is a corner of the web dedicated to things Basque. If a site ends in .eus, you will know it is Basque related. Having a domain like .eus will aid groups in promoting Basque culture and language. Thanks to Pedro Oiarzabal for pointing this out to me. Zorionak PuntuEus!

Second, as some of you may now, there has been an effort for quite some time now to get a top-level domain (think .net, .com, .edu, .es) on the internet for things Basque. I’ve featured a link in the top right corner of my page to the group that is advancing this cause, The PuntuEus Foundation. A couple of weeks back, ICANN, the organization that decides these things, approved the creation of the .eus domain. Now, there is a corner of the web dedicated to things Basque. If a site ends in .eus, you will know it is Basque related. Having a domain like .eus will aid groups in promoting Basque culture and language. Thanks to Pedro Oiarzabal for pointing this out to me. Zorionak PuntuEus!

Marraskiloak: Christmas Snails

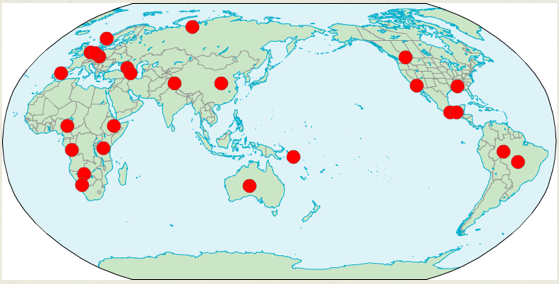

My wife sent me this interesting article about the migration of snails to Ireland. The article, which summaries this study in PLOS ONE, concludes that a specific species of snails made its way from the Eastern Pyrenees to Ireland maybe 8000 years ago. Granted, today, the eastern part of the Pyrenees is not Basque — it is Catalan — but 8000 years ago, who knows for sure. Likely, there was some Basque influence in the region, or at least proto-Basque influence, as described in this Wikipedia article. One might conclude, then, that somehow Basques, or proto-Basques, brought snails from the Pyrenees to Ireland as they explored and maybe settled Ireland. Maybe snails have something to tell us about the wanderings of prehistoric Europeans.

My wife sent me this interesting article about the migration of snails to Ireland. The article, which summaries this study in PLOS ONE, concludes that a specific species of snails made its way from the Eastern Pyrenees to Ireland maybe 8000 years ago. Granted, today, the eastern part of the Pyrenees is not Basque — it is Catalan — but 8000 years ago, who knows for sure. Likely, there was some Basque influence in the region, or at least proto-Basque influence, as described in this Wikipedia article. One might conclude, then, that somehow Basques, or proto-Basques, brought snails from the Pyrenees to Ireland as they explored and maybe settled Ireland. Maybe snails have something to tell us about the wanderings of prehistoric Europeans.

This, of course, brought to mind a story about snails. I first visited the Basque Country, during the 1991-92 school year as a student in Donostia.  So, this was my first Christmas away from home and my dad’s family — his sister, her husband, and two kids — invited me to join them in Peñíscola for the holidays. Having nothing else to do, I of course said yes. In preparation, we went into the hills outside of Ermua and collected marraskiloak — snails. It seems that snails, cooked in a tomato-based sauce, is a Christmas tradition, at least with my dad’s family, if not more widely. We took the snails with us to Peñíscola and, on the big day, my aunt prepared them, much like in the photo (swiped from this site). To eat the snails, you grabbed a shell and dug out the “meat” (I’m not really sure I want to use that word in association with snails, but I guess that’s what it technically is…) with a toothpick. You then plopped the “meat” into your mouth, chewed it up, and went for another.

So, this was my first Christmas away from home and my dad’s family — his sister, her husband, and two kids — invited me to join them in Peñíscola for the holidays. Having nothing else to do, I of course said yes. In preparation, we went into the hills outside of Ermua and collected marraskiloak — snails. It seems that snails, cooked in a tomato-based sauce, is a Christmas tradition, at least with my dad’s family, if not more widely. We took the snails with us to Peñíscola and, on the big day, my aunt prepared them, much like in the photo (swiped from this site). To eat the snails, you grabbed a shell and dug out the “meat” (I’m not really sure I want to use that word in association with snails, but I guess that’s what it technically is…) with a toothpick. You then plopped the “meat” into your mouth, chewed it up, and went for another.

Now, I don’t really recall how they tasted — it’s been over 20 years — but I do remember that as I was eating them, I ate one that tasted funny, even for a snail. Compared to the others, it just tasted off. However, not knowing better, I ate it and continued on to a few more. It wasn’t long before my stomach was rebelling against me, and not simply for eating snails in the first place. That one snail exacted revenge on my poor Americanized tummy for it and all of its comrades that had been sacrificed for our Christmas meal. Or maybe it was for dragging its ancestors to cold Ireland.

Needless to say, that was the last batch of snails I’ve had the pleasure of trying.

Thoughts on Longmire: Death Came in Like Thunder

On June 10th, A&E broadcast the episode of Longmire that features the crew dealing with a Basque community in Wyoming, Death Came in Like Thunder. For those who missed it but are interested in seeing it, you can catch it on A&E’s website.

On June 10th, A&E broadcast the episode of Longmire that features the crew dealing with a Basque community in Wyoming, Death Came in Like Thunder. For those who missed it but are interested in seeing it, you can catch it on A&E’s website.

The plot centers around the murder of a Basque sheepherder, the grandson of Basques who lost the rest of their family in the bombing of Gernika. While investigating the murder, the cast of Longmire visit a Basque festival, in progress, and the scene that a bunch of Basques (and non-Basques) were recruited to lend authenticity — you can read about the actual filming experience here. They later find one of the sheepherders, brother of the dead man, in the mountains tending sheep and then go to the home of third brother. Throughout, various references to Basques are made with varying degrees of accuracy.

Overall, given the difficulty of both cramming in as much Basqueness as possible while still staying true to history, I felt they did an admirable job. They had the sheepherder and his dog featured in the beginning of the episode, with the herder sporting a big black beret. The star, Walt, tells Vic, the sidekick, that the Basques came to Wyoming to escape World War II. This is the first inaccuracy, as the reason Basques left Euskadi are more varied and more complex, but Basques in Spain weren’t directly affected by WWII. The Spanish Civil War, on the other hand, would have been more accurate. But, there were Basques in them thar hills before the war. And most of the Basques in Wyoming, I believe, are from the French side, so maybe they could have been escaping WWII, in principle. This didn’t bother me too much, actually, as it isn’t a documentary, but one character giving his explanation. As in real life, and as is true of many Basques themselves, he can be wrong. While investigating the cabin of the dead herder, they find a postcard of Picasso’s Guernica. Thinking on the date, Walt realizes that today is the day of St. Ignacio and there is a Basque festival (never mind that St. Ignacio’s feast day is in July and this episode is supposed to take place in the spring…).

The festival is an interesting mix of both big, Jaialdi-style festivals with booths for food, sport, nicknacks, and alcohol, but with a very small festival feel. They have the Basque colors everywhere and some traditional dress (the crew made the costumes for the women dancers). There really isn’t any dancing though — the dancers carry a hoop around but there is no dancing. I guess there wasn’t time for it. There are traditional sports: tug-of-war and orga jokoa, a game in which men lift wagons and turn them as much as they can. The filming showed relatively small guys lifting what were supposed to be 400 lb weights into the wagons. That didn’t make the cut, presumably because they realized there is no way the little guys could do that. Walt and Vic approach one of the food booths and Walt eats what is implied to be a

The festival is an interesting mix of both big, Jaialdi-style festivals with booths for food, sport, nicknacks, and alcohol, but with a very small festival feel. They have the Basque colors everywhere and some traditional dress (the crew made the costumes for the women dancers). There really isn’t any dancing though — the dancers carry a hoop around but there is no dancing. I guess there wasn’t time for it. There are traditional sports: tug-of-war and orga jokoa, a game in which men lift wagons and turn them as much as they can. The filming showed relatively small guys lifting what were supposed to be 400 lb weights into the wagons. That didn’t make the cut, presumably because they realized there is no way the little guys could do that. Walt and Vic approach one of the food booths and Walt eats what is implied to be a  Rocky Mountain Oyster (in reality it was a meatball). I haven’t ever seen one of those at a festival (though I have in my parents’ fridge) but it isn’t the kind of thing I would seek out either. Otherwise, the scene has people wandering, talking, drinking, and having fun, much like any real festival. The sausages were far from chorizo, but no one could see them anyways (you can barely make out that dashing cook preparing that fine fare). I thought they did a nice job with the festival.

Rocky Mountain Oyster (in reality it was a meatball). I haven’t ever seen one of those at a festival (though I have in my parents’ fridge) but it isn’t the kind of thing I would seek out either. Otherwise, the scene has people wandering, talking, drinking, and having fun, much like any real festival. The sausages were far from chorizo, but no one could see them anyways (you can barely make out that dashing cook preparing that fine fare). I thought they did a nice job with the festival.

Next we find Walt and Vic in the mountains, confronting one of the brothers. Of particular note here are the aspens with the arboglyphs, a well-documented feature of the Basque presence in the western mountains (though I think many cultures carved images into the trees). The herder describes how the arboglyphs recount their family’s history with the land and how the timber company wants to take their land and trees. (Here, my father-in-law, a former logger, pointed out that timber companies don’t want aspens, they are useless as lumber.)

Next we find Walt and Vic in the mountains, confronting one of the brothers. Of particular note here are the aspens with the arboglyphs, a well-documented feature of the Basque presence in the western mountains (though I think many cultures carved images into the trees). The herder describes how the arboglyphs recount their family’s history with the land and how the timber company wants to take their land and trees. (Here, my father-in-law, a former logger, pointed out that timber companies don’t want aspens, they are useless as lumber.)

This brother thinks the timbermen killed his brother so he fights them and gets arrested. While in jail, he describes how his grandparents’ families were killed in the bombing of Gernika. Walt then stares at the postcard of Guernica and recounts a poem by Norman Rosten, made into a song by Joan Baez, which has the phrase “death came in as thunder while they were playing” — hence the title of the episode. He then goes on to state how the Basques would always look someone in the eye when killing them, an odd reference indeed.

The final glimpse into the Basques occurs when Walt and Vic go to the third brother’s home. There is a painting on the wall, a painting that was done by a friend in Santa Fe. But, there isn’t too much said about the Basques in this scene.

The final glimpse into the Basques occurs when Walt and Vic go to the third brother’s home. There is a painting on the wall, a painting that was done by a friend in Santa Fe. But, there isn’t too much said about the Basques in this scene.

One last thing is worth noting. The two living brothers refer to the dead brother as “basati”, which means wild or savage in Batua. Not sure if anyone would use it in the context of calling their brother crazy or wild. Anyone know?

So, in the end, things weren’t perfect. Some things they got off a bit, particularly with the motivation for the festival, but, that said, I thought it was an overall very nice portrayal of Basque-Americans. It was refreshing to have a positive spin on Basques, even if it was at the expense of those evil timbermen (sorry Dave!), as opposed to crazy jumping warriors or the stereotypical terrorist. Of course, the time of the Basque sheepherder is nearing its end. Most sheepherders are now from South America, often from Peru (at least in the Treasure Valley of Idaho). Though Basques are still involved in the industry, they have often moved up the ladder and own the outfits. Still, this was a positive portrayal, one that I’m proud to have been a part of.

In addition to the photos in this post, I’ve put a gallery of some other screen captures from the episode here.