The last few weekends, my family and I have been visiting consignment galleries, hoping to put an item up for sale. Usually, we simply hear that they aren’t interested and then we end up wandering the gallery for an hour, looking at all of the memories people are hoping to get a little bit of cash for, most of which don’t really pique our interest. Once in a while, we see something that would look pretty cool in our house, but doesn’t quite fit either our decor or our budget.

The last few weekends, my family and I have been visiting consignment galleries, hoping to put an item up for sale. Usually, we simply hear that they aren’t interested and then we end up wandering the gallery for an hour, looking at all of the memories people are hoping to get a little bit of cash for, most of which don’t really pique our interest. Once in a while, we see something that would look pretty cool in our house, but doesn’t quite fit either our decor or our budget.

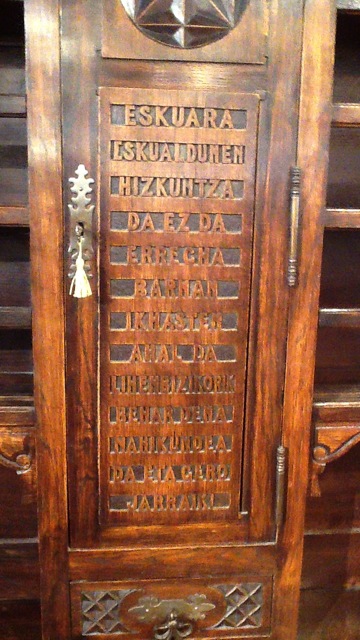

Today, however, we stumbled, almost quite literally, on the most amazing piece, not only because of its beauty, but also because the piece was adorned with Euskara.

We were wandering through the gallery, passing various pieces of furniture, most of which didn’t get much of a second glance from us. However, this ornate sideboard did catch my eye, especially when I noticed some writing on the central cabinet and rosettas that were familiar. It took me a second to register what I was seeing. A sideboard, here in Santa Fe, with a phrase in Euskara as the focus? Carved on the central cabinet of the sideboard was the following phrase:

Eskuara eskualdunen hizkuntza da ez da errecha barnan ikhasten ahal da lihenbizikoria behar dena nahikundea da eta gero jarraiki

The piece is also adorned with rosettas similar to what I’ve seen in other pieces in the Basque Country and in drawings. It has shelves for displaying plates and platters, cabinets underneath, and, as I mentioned, that central cabinet with the Euskara on the front, and a lock.

Amazingly, the gallery had only recently received it, only about a week ago, from an estate in Santa Fe.

If anyone might have any answers as to where this sideboard might have been made and when, I’d be greatly interested. Anyone know anything about this?

While it is a very cool piece, more than wanting it I’m very intrigued by it. Where did it come from? How old might it be? Why did someone in Santa Fe have it? Were they Basque, desiring something from their homeland in their home, or had they simply traveled to the Basque Country, fallen in love with the place, and purchased an admittedly extravagant souvenir? What does the Euskara translate into? I know it has to do with the language and learning, but the full meaning escapes me. It would be great to know more about the history of both the piece and the person who owned it.

While it is a very cool piece, more than wanting it I’m very intrigued by it. Where did it come from? How old might it be? Why did someone in Santa Fe have it? Were they Basque, desiring something from their homeland in their home, or had they simply traveled to the Basque Country, fallen in love with the place, and purchased an admittedly extravagant souvenir? What does the Euskara translate into? I know it has to do with the language and learning, but the full meaning escapes me. It would be great to know more about the history of both the piece and the person who owned it.

The consignment gallery that has this remarkable, at least for Santa Fe, piece is Recollections.