The Basque newspaper Deia (the oldest Basque newspaper) has been running a series of articles in their Contando Historias section about Basque words and phrases, calling out the most beautiful, the oldest, and the most common Basque words used in daily life. Such lists are always subjective and Deia has resorted to using artificial intelligence and the opinions of TikTokkers for these lists, but it still offers an interesting perspective on the language.

- The Basque word most used in daily life: Agur is the word most used in daily life in the Basque Country, even among non-Basque speakers. Nominally meaning goodbye, agur is much richer than that, with a variety of meanings based on context. In modern Basque society, agur has become an expression of identity, of cultural belonging.

- The most common Basque greeting: The Basque word aupa can be used in almost any context. Often used to mean hello, it can be used in a more formal setting with coworkers or a more familiar setting with friends and family.

- The three most beautiful Basque words (at least according to social media account Guk Green): These words are beautiful, both because of how they sound but also how their meaning arises as compound words in Euskara.

- Egunsentia (dawn): egun (day) + sentitu (feel); literally feeling the day

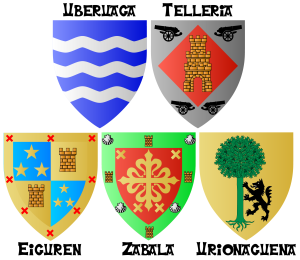

- Eskuzabal (generous): esku (hand) + zabala (width); literally wide or open hand

- Otsaila (February): otsoa (wolf) + hilabete (month); literally month of the wolf

- Basque words used to express anger: This same TikTokker Guk Green describes Basque words used when we get angry with someone:

- Txoriburu: Literally meaning bird-head, it is used to describe someone who is simple-minded.

- Pikutara joan: When you want someone to go away, you can say pikutara joan, which means “go get figs.”

- Babalore: With a literal meaning of “flower of the bean,” this again means someone who is dull or stupid. But, in the right context, it can mean beautiful.

- The oldest Basque word in daily use: I guess I’m not sure how much I trust it, but according to Deia, an artificial intelligence model has indicated that the two oldest words in Euskara that are in common daily use are aita (father) and ama (mother). They go on to describe how aita has Castilian roots and ama has similarities with the word for mother in many languages. They then discuss theories of how Euskara is related to Georgian, a theory that Larry Trask would certainly place in his bongo-bongo list.

- The most beautiful Basque names: Again turning to AI, Deia asked what was the most beautiful Basque names. I’m not sure how fruitful such queries are, but in any case, this was the answer:

- “The perception of what constitutes a “pretty” name can vary widely between different people and cultures. However, many consider the name “Ane” to be one of the prettiest in the Basque language. “Ane” is the Basque form of “Ana” or “Anna” and is popular for its simplicity and sweetness. Other Basque names that are also highly regarded include “Aitor” for males, meaning “father of the Basque race,” and “Nerea” for females, meaning “mine” or “my own.” Each of these names has a pleasant sound and deep cultural significance, making them especially beloved in the Basque community and beyond.”

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Sources are in the links in the main text.