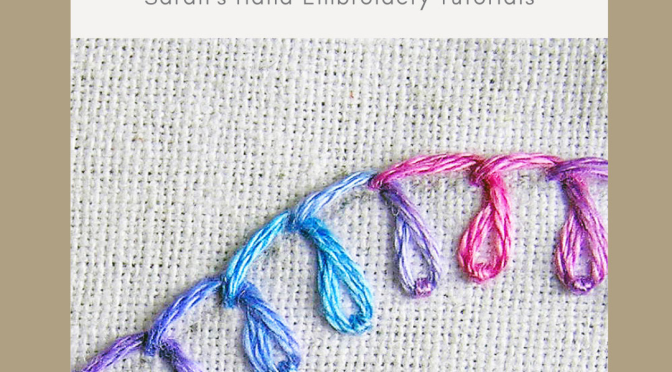

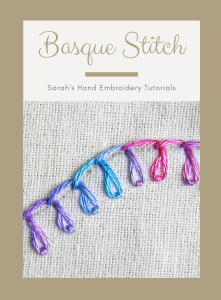

Lisa Van De Graaff (my wife), in her studies of the textile arts, ran across an embroidery stitch called the Basque stitch. She asked me about it, suggesting I do a Basque Fact of the Week about it. It turns out, there is little information about it in English beyond the fact that it is called a Basque stitch. There is another embroidery term also inspired by the Basques, the Basque knot. Beyond finding their origins in the Basque Country, there isn’t too much more out there.

- The origins of these embroidery techniques have been lost to time. There is some indication that the Basque stitch dates to the eighth century, when the Moors occupied large swaths of the Iberian peninsula and had close ties to some parts of the Basque Country. What is certain is that these stitches have been a prominent part of Basque design for many centuries.

- The Basque stitch is also known as a twisted daisy border stitch. In Spanish, it is called Punto de vasca. If there is a specific term for this stitch in Euskara, I haven’t been able to find it.

- The Basque knot is thought to be much newer in terms of its history. But, really, that’s all that seems to be known about this stitch. The Basque knot is also called a pearl stitch.

- Sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably, further confusing things.

- I’m not going to try to describe either the Basque stitch or the Basque knot here, as I wouldn’t be able to do either justice. If you are interested, you can check out this article on Piecework Magazine that goes into some of this history (what little is known) and provides step-by-step instructions as well as other links on how to make both of them.

- That’s about all I could find about the origins and history of these stitches. If anyone knows more, please share!

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: See links in the main article.

Thanks to Lisa Van De Graaff for suggesting this topic for a Basque Fact of the Week!