Balantza duen aldera erortzen da arbola.

The tree falls towards the side it’s leaning.

These proverbs were collected by Jon Aske. For the full list, along with the origin and interpretation of each proverb, click this link.

Balantza duen aldera erortzen da arbola.

The tree falls towards the side it’s leaning.

Here are a few items I’ve come across that I think are pretty interesting – I hope you do too.

The Basque Country has a long association with bears. Indeed, research by people like Roslyn Frank indicates that the Basques may have worshipped bears at one time and that Basques believed that humans were descended from bears. The importance of bears to Basque culture is reflected in their role in carnivals in various towns. However, despite this importance, real bears have all but disappeared from the Basque landscape, with the last bear sited more than 15 years ago.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Hartz, Wikipedia; European Folklore in the longue durée: Palaeolithic Continuity and the European ursine genealogy by Roslyn Frank and Fabio Silva; Frank, R. M. (2023). “The Bear’s Son Tale”: Traces of an ursine genealogy and bear ceremonialism in a pan-European oral tradition. In Bear and Human: Facets of a Multi-Layered Relationship from Past to Recent Times, with Emphasis on Northern Europe (pp. 1107-1120); Frank, Roslyn M, Recovering European Ritual Bear Hunts: A Comparative Study of Basque and Sardinian Ursine Carnival Performances. Insula-3 (June 2008), pp. 41-97. Cagliari, Sardinia. http://www.sre.urv.es/irmu/alguer/

by Sancho de Beurko Association

At barely 19 years old, Marie Irigaray Inchauspe arrived in the United States to start a new life. The year was 1904. She was accompanied by her older brother Jean who was 20 at the time. Years later, at least three more siblings—Marie, Jeanne, and Grace—joined them in pursuit of the “American Dream.” A fourth sibling, Martin, forged his own path in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Marie and Jean’s final destination was the state of Nevada, more than 5,600 miles from their hometown of Ezterenzubi in Nafarroa Beherea, or Lower Navarre.

A few months after arriving, Marie met and married the prominent Basque immigrant sheep rancher Bernard “Ben” Etchegoin, also from Ezterenzubi, on July 25, 1904, in Reno, Nevada, where they established their home. In 1906, their first and only child, Beatrice Marian, was born. Tragedy struck the family in early 1908 when Bernard was assaulted by a group of men, resulting in his untimely death, just six days shy of his 39th birthday.

Left with a daughter under the age of two and only 22 herself, life for Marie was far from easy. In 1910, she married French immigrant Auguste “August” Salet, born in Bordeaux in 1875, who had arrived in the United States around 1893. They had one child together: Eugene Albert Salet, born on May 25, 1911, in Standish, Lassen County, California.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

By 1920, Eugene and his family were living in Sparks, Nevada, where August worked as a general rancher. Although the details of Marie and August’s marriage are unclear, it most likely ended in divorce. Three years later, in 1923, Marie married Alexander Hamilton Aldrich II in Canal, Nevada. Alexander, born in Cameron, Missouri, in 1875, was a U.S. Army veteran of the Great War. Marie and Alexander had three children: Maria Eugenia (born 1924, Fernley, Nevada), Catherine May (born 1927, Lovelock, Nevada), and Alexander Hamilton III (born 1928, Reno, Nevada).

The Wall Street crash of 1929 triggered a decade-long period of poverty and unemployment known as the Great Depression, which took a heavy toll on much of American society. For Marie and her children (three of them under five years of age), it meant facing daily struggles and navigating the hardships of a rural life under one of the harshest economic crises in U.S. history. Yet, growing up amid these challenges in Nevada’s rural communities Eugene developed the resilience, courage, and determination that would shape him into a military leader of remarkable distinction.

By 1930, Eugene’s father Auguste was living in Gerlach, Nevada, working as a sheepherder. Unfortunately, he died in 1934 in Fernley at the age of 58. In 1935, after divorcing Alexander Hamilton Aldrich II, Marie married William Edward Warren (born 1875 in Virginia City, Nevada; died 1949 in Fallon, Nevada).

The matriarch of the family, Marie, lived a long and full life, passing away at the age of 90 in 1975 in her adopted home of Reno. Her first daughter, Beatrice, had died two years earlier at the age of 67 in Fallon. Her other children also lived long lives: Alexander died in 2004 at 76, Catherine in 2015 at 88, and Maria Eugenia in 2020 at 96. The family remained proud of their Basque heritage. Catherine, for example, had always hoped to visit her mother’s homeland—though, unfortunately, that dream was never realized.

Formative Years: Education, ROTC, and Early Leadership

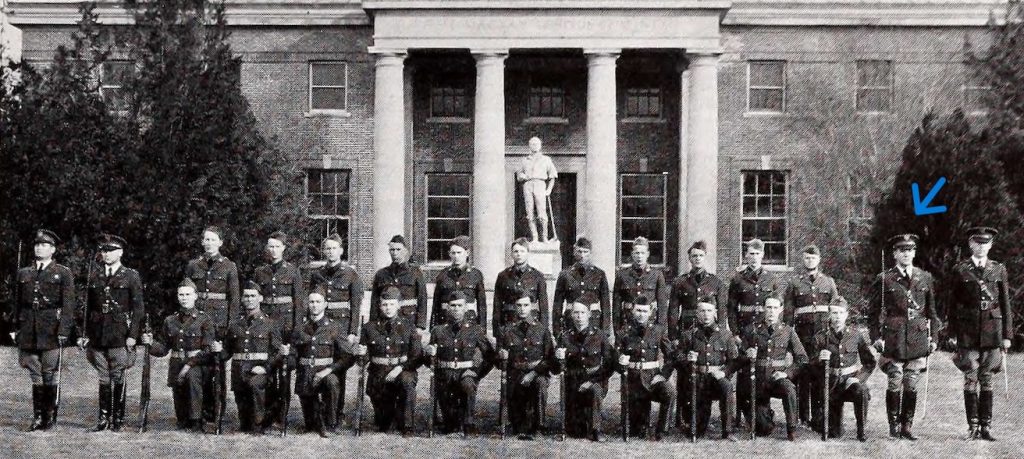

Eugene grew up in the rural town of Lovelock, Nevada, and graduated from Pershing County High School. In 1930, he moved to Reno and enrolled at the University of Nevada, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in history, education, and physical education in 1934. During his student years, he played varsity football and basketball and was an active member of several societies, including the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, Blue Key, Coffin and Keys, Sagers, Sundowners, and Scabbard and Blade. Eugene also completed the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry in May 1934, serving in the U.S. Army Reserve until 1941.

After graduation, Eugene taught and coached at Dayton High School and later became its principal. On June 13, 1936, he married the love of his life, Irene Adele Taylor, in her hometown of Buffalo, New York. He was 25 years old, and they established their home in Dayton, Nevada, where they had two children. In 1940, Eugene also managed a Shell service station in Carson City, Nevada, living there with his family and his mother-in-law.

World War II: From Operation Torch to the Heart of Europe

Eugene was called to active duty on June 16, 1941, shortly before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the United States into World War II (WWII). He was assigned to the 30th Infantry Regiment, Third Infantry Division, at the Presidio of San Francisco, California. In 1942, he was promoted from first lieutenant to captain while commanding a heavy weapons infantry company at Fort Ord, California [1].

Eugene served as an infantry platoon leader and heavy weapons company commander in North Africa and Sicily. He landed at the small port of Fedala, near Casablanca, as part of the Allies’ invasion of North Africa (Operation Torch, November 8–16, 1942). In a letter written to his mother on November 24, 1942, from Rabat, he reflected on the invasion, providing a vivid firsthand account:

“It was my first taste of fire, and I’ll probably never forget it […] Well, mother dear, here we are. Have been wanting to write ever since we arrived […] Have a great deal to tell you […] We were on the water for 15 days. On Sunday morning about 1:00 a.m., November 8, we stopped about six miles off the coast of Africa, and made ready to attack and capture it. We lowered our assault boats, climbed over the side of the transport, got into assault boats and headed for the coast six miles away […] It was still dark as the devil. As we neared the shore the French were alerted and started throwing big search lights out over the water. Then all hell broke loose. They opened up on us with big machine guns, etc. We could see the red tracer bullets coming at us through the dark; some too close for comfort. We kept on coming and finally hit the beach. It is still dark but dawn is ready to break. Then the big French guns on the coast opened up on our navy warships. What a bombardment […] I was lucky and didn’t get a scratch. Hope I can continue to be as lucky. One thing, Mom, you can tell the folks that your wandering boy led the assault waves in the great American attack of [North Africa]. Our division was the spearhead of the entire assault. We’ll give Herr Hitler and gang something to think about. Feel kind of proud, Mom, to have been a member of the assault” [2].

Serving as operations officer of the 2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, Third Infantry Division, Eugene participated in nine campaigns: French Morocco, Algeria, Sicily, Naples-Foggia, Anzio, Southern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, and Central Europe. He took part in four major amphibious assaults: the invasions of North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Southern France—often referred to as the “Forgotten D-Day.” The Third Infantry Division holds the distinction of being the only American division to engage Axis forces on all European fronts.

By mid-1944, Eugene had been promoted to major, and by January 1945, he received a battlefield promotion to lieutenant colonel, having served 27 months overseas. Remarkably, Eugene saw combat for approximately 530 consecutive days, writing to his mother after his first day on the frontline: “I was lucky and didn’t get a scratch. Hope I can continue to be as lucky.” Despite the heavy casualties suffered by the Third Infantry Division—the highest of any American division in WWII—Eugene emerged unscathed.

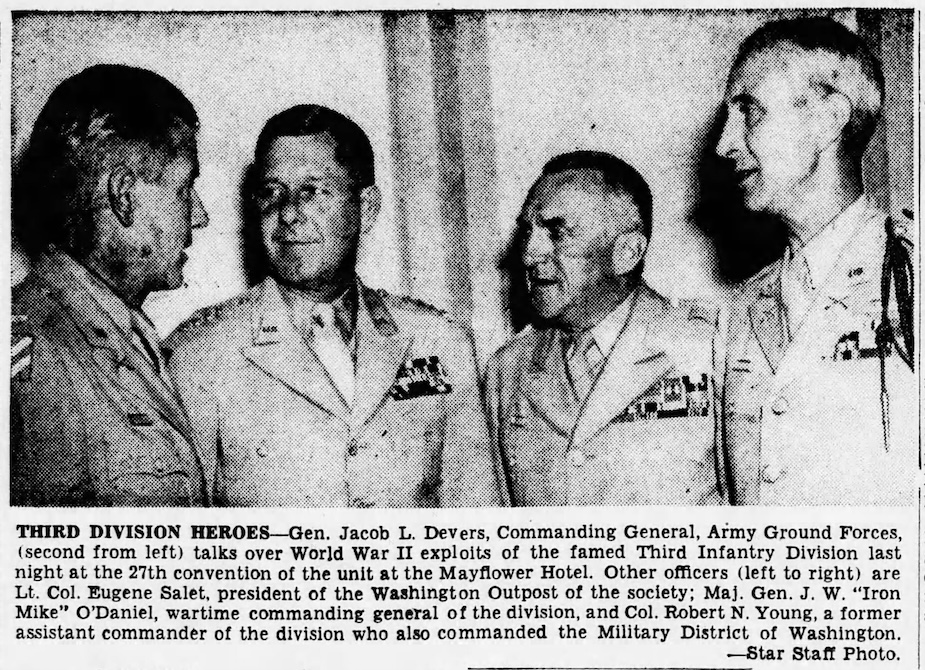

In 1945, he returned to the United States and was assigned to Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, in Washington, D.C., where he served until August 1946. For his extraordinary service during WWII, Eugene received numerous honors, including the Silver Star for gallantry in action at the Colmar Pocket, Alsace, France, on January 5, 1945; the Legion of Merit with five Oak Leaf Clusters for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States; and the Bronze Star Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters. Internationally, he was awarded the Italian Military Valor Cross, the Croix de Guerre with Gold Star, and the French Fourragère in the colors of the Croix de Guerre. Additionally, he received the Distinguished Unit Citation with one Oak Leaf Cluster and the Army’s highest civilian honor, the Decoration for Distinguished Civilian Service [3].

A Lifetime of Military Excellence and Education

Eugene had a remarkable military career that combined instruction, strategic planning, and leadership in both national and international organizations. After World War II, he served as an instructor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, shaping the education of officers at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and solidifying his expertise in military instruction.

During the 1950s, he took on roles in strategic planning and operations, including serving as senior planning officer at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) Supreme Headquarters, in Paris, France, during the Korean War, contributing to multinational coordination under General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s command. Eugene alternated between command and international administrative responsibilities, notably as a regimental commander in Germany and subsequently as deputy director and secretary of the NATO Standing Group and Military Committee, playing a key role in organizing the Alliance’s collective defense. He also served as assistant civil administrator of the Ryukyu Islands, Japan, demonstrating leadership beyond strictly military duties.

In the 1960s, Eugene focused on military education and institutional leadership, first as commanding officer of the Army Training Center at Fort Gordon, Georgia, and then as president of the U.S. Army War College and Carlisle Army Barracks, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and the U.S. Army Institute for Advanced Studies, overseeing advanced officer education and strategic programs. Recognized with the Army Distinguished Service Medal for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States, he continued his career contributing to weapons systems analysis at the Department of Defense and serving as military adviser to the U.S. mission at NATO’s headquarters in Belgium.

Eugene retired from active duty as a major general on September 30, 1970. Following his active service, he cemented his legacy in civil-military education, serving as dean and president of the Georgia Military Academy in Milledgeville, Georgia and leading the Association of Military Colleges and Schools of the U.S., nurturing future generations of military and civic leaders until 1985. [4]

Sharing a Vision: Values and Legacy

In 1967, Eugene was named Outstanding Nevadan by fellow Basque-American and WWII veteran Governor Paul Laxalt. He received an honorary doctorate in law from the University of Nevada, Reno, in 1968 and served as the commencement speaker that same year. During his address, he shared his vision for America:

“The keys which fit the door to this nation’s survival are held by each of you. These keys are faith, not fear; courage, not complacency; patriotism, not patronage; sacrifice, not selfishness.” [5]

Major General Eugene Salet Irigaray passed away on February 6, 1992, at the age of 80, at the Eisenhower Army Medical Center in Augusta, Georgia. He was buried with full military honors at Westover Memorial Park. He is the highest-ranking senior officer of Basque origin identified in the U.S. Armed Forces, according to our research.

Would You Like to Honor Veterans Like Eugene Salet?

The North American Basque Organizations, Inc. has launched a fundraising campaign to build the National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial by the end of 2026. This memorial will honor all WWII veterans of Basque origin—a place where their names, stories, and sacrifices will be permanently remembered. Your contribution is essential.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation and become part of this historic tribute. Together, we can ensure that no veteran is ever forgotten.

References

Bakoitzari berea, eta beti adiskide.

To each their own, and always be friends.

“There are at least two things that can clearly be attributed to Basque ingenuity: the Society of Jesus and the Republic of Chile.” – Miguel de Unamuno

When we think about Basque emigration and the Basque diaspora, places like Argentina and Idaho are the first to come to mind. But, as I recently learned, Chile drew a large number of Basques. Whether for the rugged landscape and nearby coast or simply because that was were earlier relatives had gone or the economic opportunities were so tempting, many Basques made their way to Chile such that, today, maybe 25-30 percent of Chileans have a Basque surname.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Chile, Wikipedia; Basque Chileans, Wikipedia; Inmigración vasca en Chile, Wikipedia; Estornés Lasa, Mariano. Chile. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2025. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/chile/ar-46423/

Over 100 years ago, in 1921, José Miguel de Barandiaran began publishing a series of articles under the banner of Eusko-Folklore. His work was interrupted by the Spanish Civil War but in 1954 he resumed publishing what he then called his third series of articles. These appeared in the journal Munibre, Natural Sciences Supplement of the Bulletin of the Royal Basque Society of Friends of the Country. While various writings of Barandiaran have been translated to English, I don’t believe these articles have. As I find this topic so fascinating, I have decided to translate them to English (with the help of Google Translate). The original version of this article can be found here.

Spirits in Animal Form

In the issues of EUSKO-FOLKLORE corresponding to the second series (Sara, 1947-1949), I collected various beliefs and legends related to deities or spirits of the earth or the subterranean regions who take the form of animals. Many of these stories feature the horse, the mare, the bull, the cow, the ram, the lamb, the sheep, the pig, the goat, the dog, the snake, and the dragon.

To the legends collected there, we can add others that develop the same themes or repeat the same images and figures.

For example, the subterranean spirit, who appears in the form of a horse and who spreads over an area whose landmarks are Laguinge (in Basque, Liginaga), Sara, Berástegui, and Lizarrabengoa. (EUSKO-FOLKLORE, 2nd Series, 1947) is mentioned in the following legend of this last locality:

On the road from Lizarrosti to Ormazarreta, a shepherd appeared on a white horse and asked him where the Putterri cave was. The shepherd showed it to him, and the knight gave him a coin as a reward, then departed and disappeared from the shepherd’s sight. And his money, in the shepherd’s hands, turned to dust.

(Told in 1955 by Don Ramón Arratibel, a native of Lizarrabengoa, currently a resident of Ataun.)

In the Putterri cave lives the being Mari, who is called Putterri’ko Dama, according to the beliefs in Arbizu, as will be explained later.

The region of the supernatural being that appears in the form of a txaal (calf) or a txekor (young bull) is marked by the towns of Camou, Iholdy, Lizarza, Ataun, Arlucea, Marquínez, Oquina, Bermeo, Oñate, and Orozco. The region of the being that takes the form of a bei (cow) or a bei-gorri (red cow) is marked by Ezpeleta, Lesaca, Amézqueta, Beizama, Motrico, and Marín (Escoriaza), according to data collected in EUSKO-FOLKLORE, 1924, pages 15, 16, 18, 19, and 20; EUSKO-FOLKLORE Yearbook, 1921, page 89. EUSKO-FOLKLORE, 2nd Series, 1947. The Legend of Marín is as follows.

A charcoal burner, during his charcoal-making days, would go every night around midnight to look at the pyre. One night, as he was going to do this work, he found an animal like a cow lying on the road. “Get up!” he said to it; but it didn’t move. “Get up!” he said again; but it didn’t move. When he had said “Get up!” the third time, it got up and, ringing a bell, “chilin, chilin,” looked at the charcoal burner and said these words: “Night for the night, and day for the day.” The charcoal burner, terribly frightened, returned home from the forest and never wanted to return to the forest.

(Communicated in 1934 by Mr. José Ascarate, from Marín).

This spirit also takes the form of urde “pig” in various folk tales from Amézqueta, Bermeo, Sara, and Marquina. In the latter town, it is called Iruztargia, related to the themes of another being named Iratxo. This figure takes the form of a fire-breathing pig that flies at night, according to legends from the Marquina region, which I collected on June 6, 1936, in the Makarda farmhouse.

Very frequently, the spirit or being of the subterranean regions appears in the form of aker “goat,” aker-beltz “black goat,” and auntz “nanny,” as we see in the legendary tales of Pierre de

Lancre and all those who have dealt with witchcraft in the Basque Country.

The name aker has left its mark on toponymy. The well-known place names are Akelarre “goat meadow,” located in Zugarramurdi and repeated on Mount Mañaria (Vizcaya); Akerlanda “goat field” in Gautéguiz de Arteaga; Akelarren-lezea “cave of the Akelarre” located next to the Akelarre meadow in Zugarramurdi.

Current legends from Urepel tell us about the goat in the cave of Mount Auza, and those from Villafranca refer to the spirit that appears in the form of a goat. See EUSKO-FOLKLORE, 2nd Series, 1948 and 1949. The goat is considered a protective animal for livestock in the stable and the flocks (Ataun, Sara). For this reason, in some houses they raise a goat—black being preferred—to prevent diseases in the livestock.

In St-Jean-le-Vieux (in Basque, Donazaharre), the lady of the Luko house told me in 1945 that an azti (diviner and healer) called Maille lived in the Iberteia house in that village in the middle of the last century, who, before issuing his oracles, consulted a goat he owned. It is said that his prophecies, especially his curses, were unfailingly fulfilled.

The subterranean spirit rarely appears in the form of a dog. However, certain legends mention him, such as those of Olanoi (Beizama) from Motrico and Berriz. EUSKO-FOLKLORE. 2nd Series, 1947 and 1949.

Many legends refer to the spirit known as Sugaar “male serpent” or Sugoi, who appears in the form of a serpent.

Toponymy has echoed these legends, as evidenced by the name Sugaarzulo “chasm of Sugaar” used to designate two caverns in Ataun, located above the Arrateta Gorge and the Aspildi Ravine, respectively.

The same spirit appears to be the one who appears in other legends with the names Egansube, Ersuge, Erensuge, Herainsuge, Iraunsuge, Igensuge, Edensuge, Edaansuge, Lerensuge, etc. He is mentioned in many folk tales we have collected in Orduña, Dima, Ochandiano, Lequeitio, Mondragón, Ataun, Zaldivia, Rentería, and Zugarramurdi. Sara, Ezpeleta, St-Esteben, Uhart-Mixe, Camou, Alzaay, Liginaga or Laguinge. etc. (EUSKO-FOLKLORE, 2nd Series, 1949).

Geniuses with a human or semi-human form. Mari

The most prominent deity of the underworld is Mari, as we can infer from the beliefs and legends that refer to her. She receives various names, depending on the locality, such as Mari, Mari-muruko “Mari of Muru” (in Ataun and Elduayen), and Mari-mur (in Leiza), Mamur (in Vera), Maya (in Oyarzun), Mariburrika (in Berriz and Garay), Gaiztoa “the evil one” (in Oñate), Yona-gorri “she of the red dress” (in Lescun), Sugaar (in Ataun), etc. (1). Mari, Dama, and Señora are equivalent. Mari is also supplanted by Lamiña in many cases.

(1) José Miguel de Barandiarán: Contribución al estudio de la Mitología vasca (en “Homenaje a Fritz Kruger”, tomo I, Mendoza, 1952)

Various themes have centered around the deity or name Mari: A beautiful woman combing her hair while sitting in the sun at the entrance to her cave; the mistress of all the beings or spirits of the subterranean regions; she forges and directs storms; she produces rain and drought; she punishes liars; she lives on “yes” and “no”; she takes the form of various animal species (heifer, bull, ram, goat, horse, mare, snake) and certain atmospheric phenomena, such as a meteor, a cloud, etc.; she holds disobedient young people captive; she is incompatible with anything of Christian significance, etc.

We have collected many Mari legends in various publications, such as EUSKO-FOLKLORE (1921, pp. 9-17; December 1922, pp. 29-30); in Mari o el genio de las montañas (“Homenaje a Don Carmelo de Echegaray”. San Sebastián, 1923); In Die prahistorischen Hohlen in der baskischen Mythologie (“Paideuma,” vol. II, no. 1-2. Leipzig, 1941) and in its Spanish translation Las cavernas prehistóricas en la mitología vasca (“Cuadernos de historia primitiva,” Madrid, 1946) and in Contribución al estudio de la mitología vasca (“Homage to Fritz Kruger,” vol. I. Mendoza, 1952).

Jean Barbier included in his Légendes du Pays Basque d’aprés la tradition (first part, no. 6; third part, no. 2. Paris, 1931) some themes that are part of the Mari cycle in several Basque regions. Barbier calls her Bas’Andrea, “the lady of the forest or wilds.”

W. Webster mentions some of the Mari themes in his Basque Legends (London, 1879, pp. 47-48), as does Cerquand in Légendes et Récits Populaires du Pays Basque (Pau, 1876, I, pp. 33 and 34).

Azkue included several legends from the Mari cycle in Euskalerriaren Yakintza (Vol. I, Chapter XV, Nos. X and XII. Madrid, 1935; Vol. I, Nos. 194, 203, and 235. Madrid, 1942).

To the legends and traditions collected in the preceding publications, we can add others, which we will copy below.

The elderly J. M. Goiburu, who had been a shepherd in Aizkorri since childhood, told me in 1943 that in his hometown of Ursuaran, he once saw the Lady of Amboto (another name for Mari) soaring through the air from Aizkorri toward Amboto, in the form of a woman wrapped in flames and bent like a sickle.

In Mañaria, they call this spirit Mariurreka, and they say she spends seven years in Amboto, seven in Oiz, and seven in Mugarra (the rock of Mañaria).

In this village, they also call Saint Anthony’s cow, or Coccinella septempunctata, Mariurreka or Mariurrika.

Abbé Larzabal, from Ascain, told me in 1948 that, according to an old belief in that village, a lady lived in a cave called Arrobibeltxa, who was depicted sitting on a golden seat.

In Lacunza, they call her Illunbetagañe’ko Damea and Beraingo-lezeko Damea.

In Arbizu, she is known by the name Putterri’ko Dama “Lady of Putterri” (Putterri is a mountain in that region). And in Urdiain, she is known by the name Baso’ko Mari “Mari of the Forest,” according to what a shepherd from that village in Urbasa told me in 1921.

In Ispaster, when the peak of Otoyo was crowned with clouds, people frequently said: Marie labakok labakoa dauko da euria eingo dau laster (Mari of the oven bakes the bread, and it will soon rain), according to data collected in that village in 1927.

On the hill near the Adurria basseri (Ispaster), there is a cave called Damazulo. At its entrance, there is a hut. It is said that the Lady of Amboto came to this cave to spend some time.

An old woman from the Dorrea house in the village of Udabe (Navarra) claimed that a spirit named Mari-burute lived in a cave on the mountain above that village, and added that the local priest had to go once a year to bless the cave; otherwise, storms and hail would fall throughout the year.

Doña Juliana de Azpeitia sent me the following note from Evaristo Gómez Inchausti, from Zumárraga, who had given it to her in 1907:

When the sun and rain coincide, the Lady of Amboto emerges from her cave and combs her beautiful hair with a golden comb. And on Friday afternoons, at two o’clock, the enemy from hell [the devil] comes to comb her hair.

According to a report from Azcoitia, it is Maju, Mari’s husband, who occasionally goes to meet with her, thereby causing a furious storm.

In Gorriti, this spirit is called Adureko-Mari, who lives in a chasm in Aralar from where she draws storm clouds. It is said that a priest performs a spell at the mouth of this chasm once a year. If Mari is inside at that moment, there will be no hail in the region for that year.

According to a report by Father Gregorio Bera, it is said that the Lady of Amboto spends six years on the rock of Amboto. She then moves to Gorbea (according to others, to Atxali, Yurre), where she remains for another six years. As she moves from one place to another, she throws off sparks. (Reported in 1921).

Father Bera himself told me that in Abadiano there was a belief that a great lady named Mariurraka lived on the Amboto rock, who used to spin thread. From time to time, she would go to Mount Kampanzar, surrounded by great fires. She would then return to Amboto.

The following legend is also from Abadiano:

A king of Navarre said: “I will give one of my daughters in marriage to whoever defeats a black man from here in wrestling.” So the man from the house of Abadiano, called Muntzas, came and defeated that black man. The king gave him a daughter of his own, as he had said, and that daughter of the king and that man from Abadiano, married, came to live in the Palace of Abadiano, located in the Muntzas neighborhood. They had sons and daughters: Ibon was the eldest, and Mariurrika, full of pampering, was the youngest.

One day, a maid and Mariurrika, in concert, planned to kill Ibon because the inheritance was due to him. And so, they went once to Amboto to spend a day. After they arrived, they sat down to eat, and while they were eating, they gave Ibon a lot of wine to drink, and they got him drunk While he was asleep from drunkenness, the maid and Mariurrika pushed him and threw Ibon down the rocks, where he died.

After he returned home, Mariurrika told his father that Ibon had fallen from the rocks. But his conscience accused him of having done wrong.

When night fell, while Mariurrika was in the kitchen, the devils came down through the chimney. When Mariurrika was dead, he flew from Amboto to Oiz, in the form of a flame.

Amboto has a cave—the cave of Mari—and another in Sarrimendi.

(Report by S. Gastelu-iturri, native of Abadiano. Year 1931).

MARIBURRIKA OF SARRIMENDI (1)

(1) Sarrimendi, mountain of Sarria in Berriz (Vizcaya).

The people of Andikona and those of Sarria (2) were always arguing over water. A stream flowed from Mount Oiz, and those of Andikona blocked the road to Sarria and carried the water to Andikona. And those of Sarria blocked the road to Andikona and carried the water to Sarria.

(2) Andikona and Sarria, two neighborhoods of Berriz.

One day when the people of Andikona had turned off the water, the demon appeared to the lady of Sarribeiti and asked what she would give him so that he would always send the water to Sarria. And the lady told him that she would give him her daughter.

Upon hearing this, the demon sent the water to Sarria and claimed the daughter from the lady. And the lady told him that she would send her daughter to the meadow that is next to the cave of Mariburrik de Sarrimendi to take care of cows. There, he could kidnap her.

The little girl went to collect the cows, and when she called “white, white,” Mariburrika came out of the cave and snatched the girl and took her to her lair.

Next to the Urizar house, there is a small cave—which they say is the end of Mariburrika’s cavern—and there they found the girl’s clothes.

(Report by Juan Loizate, from Berriz. Year 1931).

IN MARIN AND ESCORIAZA

A mother and daughter lived in a house. The daughter was always occupied with adorning her body, disregarding her mother’s orders. One day, she gave her mother a disrespectful answer, and her mother, angry, cursed her: “May heaven and earth not receive you again.” That’s why she now always wanders in the air. She resides in the Amboto cave by day, spinning and spinning; but she can’t make any thread. At night, leaving the cave and throwing sparks, she moves to other places.

(Report by José Azcarate, from Marín, 1934.)

A rich lady lives in Amboto, and three times a year she comes to Kurtzebarri (1). She flew by in the shape of a very beautiful moon; but a half-moon. Faster than lightning, shooting fire all around. It used to happen in the past, and according to our grandmother, it was a sight to behold.

(1) Kurtzebarri “New Cross”, mountain of Escoriaza.

(Reported in 1935 by José Aramburuzabala, from Escoriaza.)

José Miguel de Barandiaran

Azken gaizto egingo duzu, txoria, gazterik egiten ez baduzu habia.

You will have a sad end, bird, if you don’t make your nest while you’re still young.

The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know about Basque culture. When she accepted her award for her dedication to Basque culture at the Zortziak Bat symposium, Meggan Laxalt Mackey emphasized the role of auzolan – community work or more broadly collaboration – in her work. I hadn’t heard of that concept before, but it is central to Basque culture. It embodies the collective spirit, of working together to make your community better.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Estornés Zubizarreta, Idoia; Garmendia Larrañaga, Juan. Auzolan. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2025. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/auzolan/ar-16620/; Auzolán, Wikipedia; Auzolan, Wikipedia;

Azeria solas ematen zaukanean ari, gogo emak heure oiloari.

When the fox is engaging you in conversation, keep an eye on your chicken.