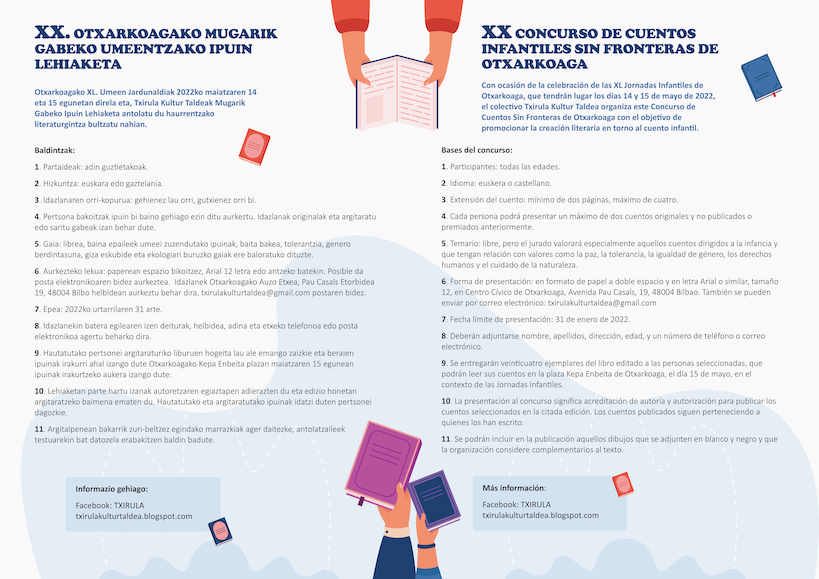

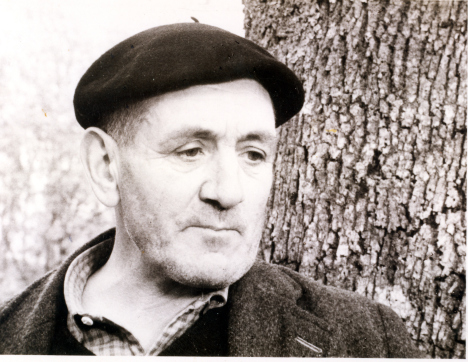

During World War II, the Basque Country occupied a special geopolitical position which provided unique opportunities to contribute to the effort against the Axis powers. The French side was of course occupied by Germany, but the Spanish side remained neutral. This led to networks to get soldiers, refugees, and politicians across the French-Spanish border and ultimately to freedom, networks such as the Bidegaray network led by Ana María Bidegaray. Many Basques from both sides were involved in these networks. Perhaps one of the most recognized was Florentino Goikoetxea, a humble hunter and smuggler from the Pyrenees mountains.

- Florentino Goikoetxea Beobide was born on March 14, 1898, in Hernani, Gipuzkoa, where he lived until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. He took refuge in France, making his home in Ziburu, Lapurdi. He became friends with Kattalin Aguirre, who was part of the French Resistance during World War II, and through her he became involved in the Comet Line.

- The Comet Line was a network passing through Europe where downed Allied airmen and other refugees would be taken from Belgium, passed through France to Spain and ultimately taken to Great Britain. It was first led by Andrée de Jongh (“Dédée”) and the majority of those involved where women, often teens.

- Florentino was one of the men involved. Since his childhood, he had been a hunter, and roamed the Pyrenees mountains. He turned his knowledge of the terrain toward smuggling (he was a mugalari) as he became older. He then adapted his deep familiarity of the border to smuggling people on the Comet Line. In 1941, he began working with the Comet Line and, in April, 1942, he became their principal guide.

- He worked as part of the Comet Line until 1944. During that time, he helped some 227 airmen and French and Belgian agents cross the border and find their way to freedom.

- He also worked with other networks, including those led by the United States, where he passed mail back to the resistance. On one of his trips, on July 26, as he was returning from a walk, he was surprised by German patrol guards and shot four times, breaking his leg and shattering his kneecap. He was taken to the hospital in Baiona. The Comet Line, in a plan coordinated by Elvire de Greef and executed by two German-speaking Basques who pretended to be Gestapo agents, conspired to help him escape, eventually getting him to Biarritz, where he remained until the liberation of the region a month later.

- For his efforts, Florentino, a near-illiterate Basque smuggler, received multiple recognitions and honors, but only after Franco died as he was still wanted by Spanish authorities. His awards included the George Medal from the UK and the French Legion of Honor. In one ceremony with the British royal family, he was asked what his occupation was, to which he replied “the import-export business.” He died on July 27, 1980, in Ziburu.

Primary sources: Intertwined: The Tail of the Comet, Vince Juaristi; Goikoetxea Beobide, Florentino. Enciclopedia Auñamendi. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/goikoetxea-beobide-florentino/ar-66614/; Florentino Goikoetxea, Wikipedia.