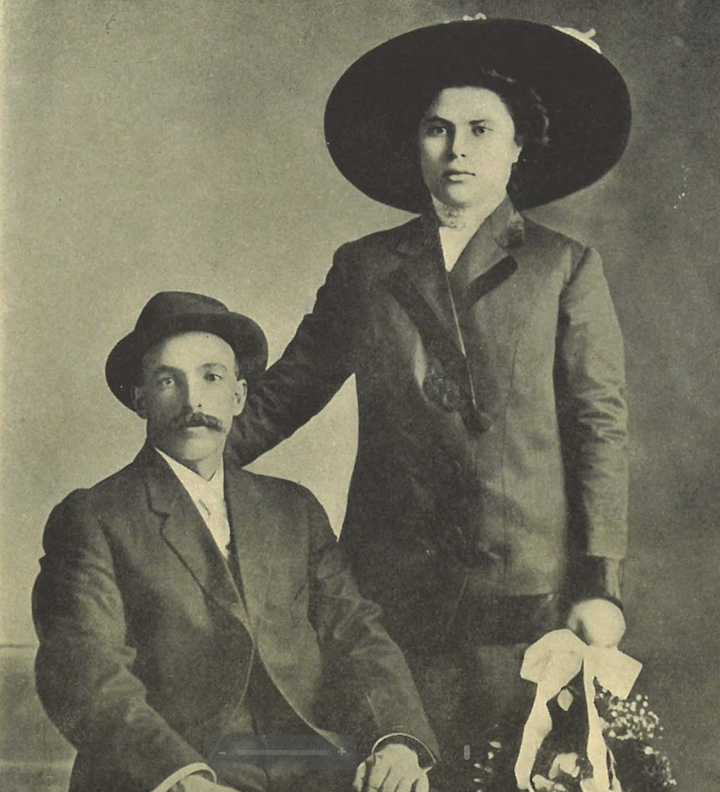

Happy Mother’s Day! In honor of all of the moms out there, this Basque Fact of the Week is about the Etxekoandre, or the Mother of the House. Women have historically held a higher position in Basque society than in many other places, leading some to argue that pre-Christian Basque society was matriarchal, or, at the very least, a society where men and women held positions of importance and power more equally. At the center of this society is the Etxekoandre.

- When the Romans first arrived in the Basque Country, one of the things they found most shocking was the fact that women were often the keepers of the house, taking care of the home and the surrounding orchards, and even giving their siblings dowries so that they could get married. That women were in control of and distributed the wealth of a household was unknown to the Romans. Strabo, one of those civilized Romans, remarked that the Basque Country had “a sort of woman-rule—not at all a mark of civilization.“

- In contrast to much of the rest of Europe, in the Basque Country, houses were often handed down not to the eldest male, but to the eldest child, including daughters. This difference may be explained by the higher role women held in Basque society. Men were often out, grazing their herds or at sea, and women were the head of domestic life. This increased her dignity and prestige, which, in turn, favored the social and political situation of women within Basque society.

- The etxekoandre was the owner of the house in many ways. She was the only one with keys to all rooms and no room could be opened without her consent. She kept the healing jars and herbs, as she and her fellow etxekoandreak were the healers of the village (sometimes hunted and persecuted as witches). And, of all of the chairs in the house, hers alone had armrests. When she was near death, she passed this chair to the next woman to become the next etxekoandre of the house.

- She was responsible for keeping communion with the ancestors of the house. She represented the house in the yarleku that she owned in the parish Church, as well as in the grave, and presided over the sacred acts and ceremonies that take place there, including keeping the light of the argizaiola.

- As the domestic priestess, the etxekoandre was also the one who took care of the dead. She prepared the corpse — closing its eyes, washing the body with holy water, dressing it — and she organized all of the funeral activities.

Primary sources: Matriarcado vasco: historia de un territorio en el que ellas han mandado siempre by Maialen Ferreira in El Diario; Auñamendi Entziklopedia. ETXEKOANDRE. Enciclopedia Auñamendi, 2020. Available at: http://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/etxekoandre/ar-35519/; “La baserritarra en el caserio vasco” by Pedro Berriochoa Azcarate, in Jornaleras, campesinas y agricultoras. La historia agraria desde una perspectiva de genero, edited by Ortega López, Teresa María.