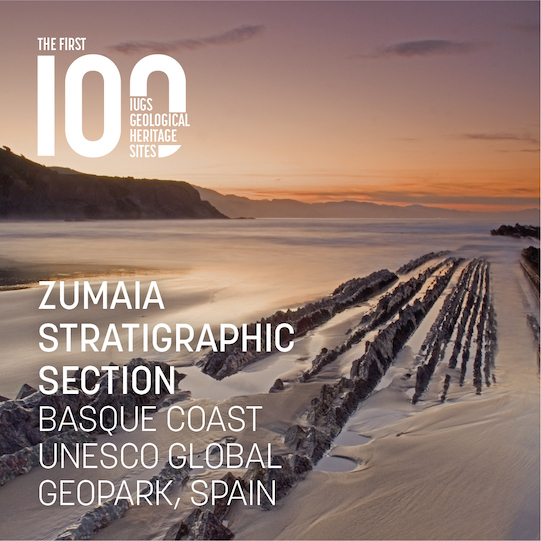

During the week of October 25-28, Zumaia, a small town of about 10,000 people, hosted an event celebrating the 60th anniversary of the IUGS – the International Union of Geological Sciences. At this meeting, the IUGS announced the first 100 geoheritage sites, “key place[s] with geological elements and/or processes of scientific international relevance, used as a reference, and/or with a substantial contribution to the development of geological sciences through history.” Zumaia not only hosted the event, but was recognized as one of these new geoheritage sites.

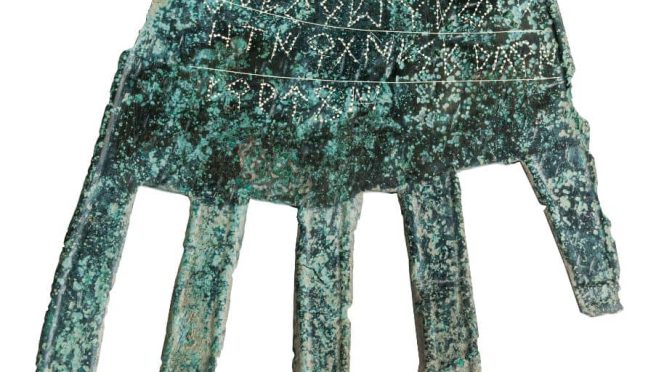

- Zumaia is a town on the coast of Gipuzkoa. It was founded on July 4, 1347, when Alfonso XI of Castile granted the people of Seaz the right to establish a new town.

- A flysch is a geological formation in which alternating layers of rock, often shales and sandstones, that are formed during sedimentary deposition and then pushed up via tectonic motion to be exposed to the surface. They give us a direct look at the geological processes the happen at the bottom of oceans. The flysch in Zumaia, stretching some 10 kilometers along the Basque Coast, is particularly famous for its unique geology.

- The flysch in Zumaia started forming some 110 million years ago and accompanied the processes that ultimately led to the formation of the Pyrenees. As the Bay of Bizkaia opened, the relatively tranquil sea that filled it in allowed for various layers of sediment to be deposited. This included limestone, marl, and sandstone. Eventually, the Iberian peninsula collided with Eurasia, causing these layers to fold and break. Now tilted and exposed to the air, these layers were eventually eroded over the last 2 million years until they formed the marvelous structures we can see today.

- The Euskal Kostaldeko Geoparkea, or Basque Coast Geopark, is home to the Zumaia flysch, and encompasses Deba and Mutriku as well. In 2015, the park was designated a UNESCO Global Geopark. Through the park, you can arrange tours to visit the flysch either by foot or by boat.

- Zumaia was host to the 60th anniversary meeting of the IUGS – the International Union of Geological Sciences. There, they announced the first-ever “First 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites,” an effort to recognize and protect the unique geological history of the planet – the Earth’s geoheritage. 100 geological sites from around the world were recognized, including the Grand Canyon in the United States, the longest underwater cave system in the world which is in Mexico, and the Genbudo cave in Japan where geomagnetic reversal was first proposed. A downloadable book describing all 100 sites can be found here.

- The flysch of Zumaia also made the list, for being “One of the best exposed, most continuous and highly studied outcrops of deep marine sediments in the world.” It “provides critical information about climate and biosphere evolution through critical intervals of geological time.” They have also been important in developing our understanding of major events in the Earth’s history, including “the mass extinction at the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) boundary and the global warming across the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).”

Primary sources: Geoparkea; IUGS Geoherigate Site; Flysch, Wikipedia; Hilario Orús, Asier. Flysch de Zumaia. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/flysch-de-zumaia/ar-152134/;