I just discovered Bertrand Linne and his art. He’s from Hendaia. His art is very geometrical. It’s just great, capturing the essence of his subjects with lines and a few colors. Every image looks like a stained glass window. Ikaragarria da!

I just discovered Bertrand Linne and his art. He’s from Hendaia. His art is very geometrical. It’s just great, capturing the essence of his subjects with lines and a few colors. Every image looks like a stained glass window. Ikaragarria da!

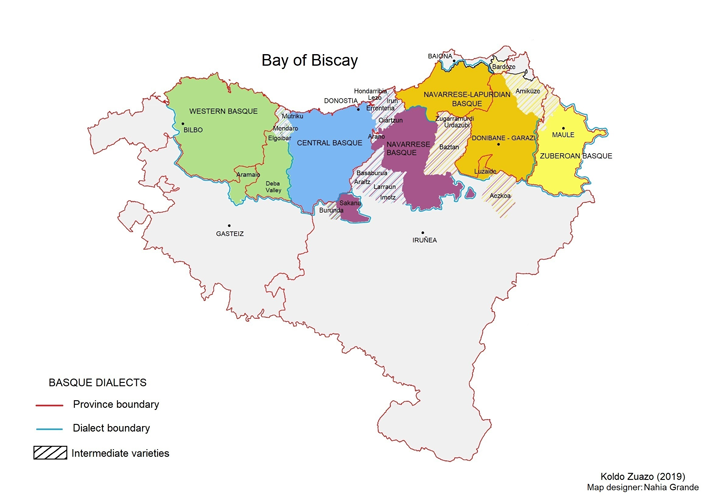

One of the challenges I had when I tried to learn Euskara in Donostia was that I was learning Batua but when I went to visit my dad’s family, they spoken the Bizkaian dialect and I had a hard time understanding them. When I told my dad about it, he nodded, saying he couldn’t understand the Basque from Iparralde. Indeed, it almost seems that every valley, every baserri, has its own dialect of Euskara. One of the goals of standardizing Basque is to make communication in the language easier, but of course that comes with loss of richness of the language.

Primary sources: Auñamendi Entziklopedia. DIALECTO. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/dialecto/ar-44516/; Basque dialects, Wikipedia; Euskalkiak.eus

Kepa and Latxe were back at the baserri, sitting at a table with Olatz/Marina and a few other of her acolytes. To be honest, Kepa wasn’t quite sure how to think about Olatz’s followers. They seemed to blindly follow her direction, but he had to admit that their cause seemed just, at least as far as he understood it. Is a demogauge ok if they are pointing people in a good direction?

Kepa decided to table that thought for the moment. It would prove a fruitful and interesting discussion point with Maite sometime when they were bored, sitting in some bar somewhere waiting for the next mission to chase a zatia. For the moment, he was focused on making that a reality, to find Maite and the zatia and escape this bubble.

Looking across the table at Marina (he could tell she was in control because of the slight distance in her eyes), he asked “How do we free Maite?”

Marina looked back at Kepa and he could tell that she was supressing a sigh. It seemed to him that she would be happy enough letting Maite rot with de Lancre if she could win her revolution. He wasn’t so sure that Marina cared to pop this bubble.

“Well,” began Marina, speaking in Olatz’s voice, “we need to get into that tower. I’m sure Salazar is holding Maite there.”

“How can you be so sure?” asked Kepa.

One of Olatz’s eyebrows raised. “Let’s just say that he has a fondness for a certain type of young women. He’ll keep her close.”

Kepa grimmaced. He couldn’t image de Lancre’s hands touching Maite, not that he thought she would ever allow it.

“Fine. How do we get into the tower?”

Olatz/Marina looked at the others around the table. Some shook their heads, others simply looked down at the table. No one offered any ideas.

“Well,” started Latxe after an agonizing silence. “We could use the nanobots.”

“Go on,” said Olatz after Latxe had paused.

“Just like we do here. We can use the nanobots to create temporary doors into the tower and stairs between floors. We can also use them to disguise us from any monitoring equipment.”

“Excellent!” exclaimed Kepa, smacking his hands on the table as he stood up. “Goazen. Let’s go!”

“Hold your horses,” said Olatz in a stern voice. She turned to Latxe. “But…?” she asked.

Latxe smiled weakly. “But,” she said, “we only have the ability to hijack a relatively small number of nanobots. Only enough for one, maybe two, people.”

“What?” exclaimed Jorge. “Two people to storm Salazar’s tower? Are you insane?”

“We aren’t storming it, exactly…” began Latxe as her voice trailed off.

“It’s suicide!” continued Jorge. “Even with the nanobots covering your tracks, it would only be a matter of time before they failed or you ran into humans that couldn’t be deceived.” He turned to Olatz. “Tell them, Olatz!”

“What else can we do?” asked Olatz.

Jorge threw up his hands. “If they get caught, and reveal our ability to hijack the nanobots, we are all screwed.”

“Do you have another idea?” asked Latxe, defiantly.

Jorge stuttered, looking first at Olatz, and then Latxe. He then looked at Kepa and saw the hope on his face. His own face fell.

“No,” he said, glumly.

If you get this post via email, the return-to address goes no where, so please write blas@buber.net if you want to get in touch with me.

Leading scientist – once president of the French Academy of Sciences – and key promoter and defender of the Basques. Anton Abadia was both. During his career, he won numerous scientific accolades while also founding the first festivals celebrating the Basque people and their culture. His impact was so great that, in 1997 – one hundred years after his death – his life was celebrated by both academics and politicians.

Primary sources: Auñamendi Entziklopedia. Abadia, Anton (1810-1897). Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/abadia-anton-1810-1897/ar-611/; Antoine Thomson d’Abbadie, Wikipedia; Anton Abidia, Wikipedia

“What is this?” asked Maite.

De Lancre had taken her outside of the city using one of the strange egg-pods. Maite had almost had a panic attack, sitting that closely to him inside the egg, but had fought to keep her emotions under control. It had been a relief when they arrived and the egg dissolved around them.

In front of her was a massive complex. A large domed building sat above another, larger building. Maite watched as the building complex seemed to undulate, almost shimmering like the landscape behind a hot road when the waves of heat warped the surrounding air. She assumed this was due to the invisible nanobots constantly building and rebuilding parts of the complex.

“This is the AI,” replied de Lancre. “The main AI is housed in the dome and, underneath, is a fusion reactor that powers the AI.”

Maite gasped. “A fusion reactor just for the AI?”

De Lancre nodded. “Computing at the scale of this AI, which is essentially the brains for the whole city and beyond, requires a huge amount of energy.”

“I would never have imagined…” began Maite, her voice trailing off in awe.

“Imagine how I felt,” chuckled de Lancre. “At least, in your time, you have a concept of fusion energy and artificial intelligence. In my time, we didn’t conceive of running water, let alone electricity.”

“So, this AI runs everything?” asked Maite.

“Well, it doesn’t control what I do, or any individual for that matter, but it manages the city and, in particular, the nanobots. You can think of this as the nest from whence the nanobots – the ants – come and go.”

“I guess that analogy only goes so far,” said Maite, “as ant colonies don’t have a central intelligence guiding them – ants are all autonomous.”

De Lancre looked at her with admiration. “I didn’t realize that. But, yes, the nanobots are not autonomous, they get direction from the AI here. Out in the field, they communicate with one another, exchanging information and orders, until they come back here to bring back raw materials.”

“Are any of you concerned that the AI might go rogue? Might do things that are not in the best interests of humans?”

De Lancre stared at the dome before them. “I admit, I personally haven’t given it much thought. If it does start doing something like that, I can always escape with the zatia and pop the bubble. I guess the engineers and scientists who built the thing must have thought about it, but it’s evolved so far from their original designs, I doubt even they know what it is capable of.”

As de Lancre spoke, Maite swore she saw a sudden but subtle shift in the pattern that the buildings around her were being constructed and torn down, but when she looked again, everything looked like it had before.

If you get this post via email, the return-to address goes no where, so please write blas@buber.net if you want to get in touch with me.

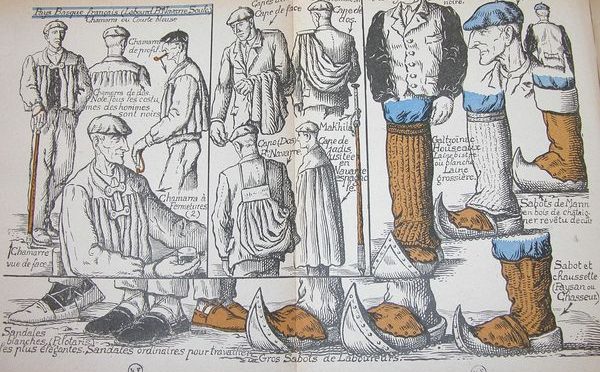

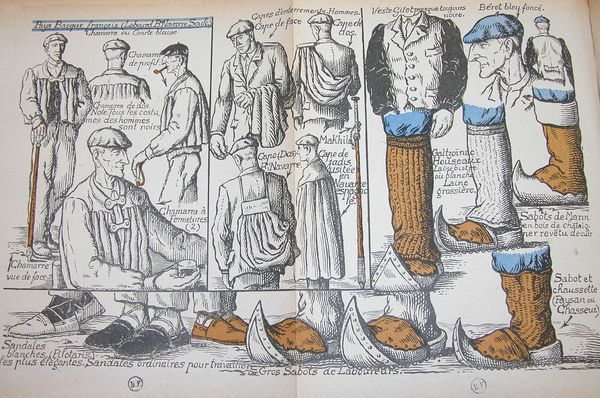

The last one hundred years has seen more change than any other time in our history. The way that place such as the Basque Country are now would be shocking to anyone born one hundred years ago, and the reverse might be true as well. So much has changed. Having a looking glass into the past helps us appreciate that change. Jean Paul “Pablo” Tillac gave us such a looking glass. He devoted some 2000 drawings to Basque subjects, capturing them in their daily life as they played pelota, attended church, or participated in carnivals.

Auñamendi Entziklopedia. Tillac, Jean Paul. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2022. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/tillac-jean-paul/ar-139866/

Maite just sat in her room, racking her brains for some kind of plan to escape de Lancre’s clutches. But, she could see no way out. She was stuck on the top of one of the tallest buildings in Bilbo and she was sure those damned spheres would alert de Lancre to anything she did.

Her door opened suddenly and she looked up. One of those spheres hovered at the entrance, just floating in the air like a giant eye, staring at her.

“What?” she exclaimed exhasperated. “Can you read my mind too? I wasn’t going to do anything.”

The sphere just floated there. If it understood her, it didn’t acknowledge it.

Maite stood up and sighed. “I assume this is some kind of summons then?”

As she made toward the door, the sphere turned and started floating down the hall. Instead of out to the patio, where at least Maite could take in the admittedly magnificent view of the city, the sphere took her in the opposite direction. At the end of the hall was a large double door, made of some shiny metal. The sphere stopped. Maite stopped. Nothing happened. She looked up at the sphere, which just floated in the air.

“Ugh,” she said as she approached the door. It opened silently, each side sliding into the neighboring wall. Inside, she saw a large desk surrounded floating displays. She recognized a few. One was of the city from above. Another showed the plaza outside the airport where she and Kepa had first encountered the flying eggs. Others displayed more intimate settings, seemingly the inside of people’s homes. A shiver ran down Maite’s back as she watched on one display a mother and father make dinner for their two children. Were these enemies of de Lancre that he might be planning to eliminate?

De Lancre sat behind the big desk. As Maite entered the room, he waved his hand and all of the displays dematerialized, leaving the room empty and spartan. Beyond de Lancre’s large desk, there was a small table surrounded by chairs in one corner, and another large chair on the opposite side of the desk from de Lancre. There was no art on the walls, nor shelves with momentos or books. Just plain bare walls.

De Lancre stood up as the desk rotated around him such that it was now behind him. He approached Maite and offered his hand. “I want to show you something,” he said.

Maite, her hand remaining at her side, replied. “What if I don’t want to see it?”

De Lancre tilted his head to the side. Three of the spheres floated into the room, small bolts of electricity arcing between them. They surrounded Maite’s head, one at each side and one behind, with de Lancre in front. “I hate to use them, but I won’t hesitate.”

Maite sighed, extending her hand.

De Lancre smiled.

If you get this post via email, the return-to address goes no where, so please write blas@buber.net if you want to get in touch with me.

Perhaps the best steak I have ever had was at one of the Txokos – the gastronomic clubs – in Donostia. A few friends of mine were members and took me for dinner one evening. In the heart of the old town – the Parte Vieja – of the city, it was an almost nondescript building from the outside, but inside was filled with tables for dining and a large kitchen. Txokos are so important in Basque society, at least for men, that my uncle built a small one in the back of his garage, a place he could escape and have dinners with friends.

Primary sources: Estornés Zubizarreta, Idoia; Arpal Poblador, Jesús. SOCIEDADES POPULARES. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2022. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/sociedades-populares/ar-110524/; Txoko, Wikipedia

Kepa stood in the small plaza shielding his gaze from the overhead sun as he looked up at the tall building towering over him. Like many of the buildings in the city, it curved in ways that were both unnatural and natural, mimicking less the rigid buildings of his own time and reminding him more of a forest of trees, albeit one that grew vertically. Greenery sprouted from every conceivable crevice and angle. New balconies and canopies grew almost spontaneously as others dissolved into nothingness as he watched.

“The nanobots do that?” he asked.

Next to him, Latxe nodded. She had been the only one willing to come out with him. Olatz didn’t dare appear out in the open and Kepa hadn’t really made friends with anyone else at the baserri. They all viewed him as some ignorant hick and barely tolerated him. For reasons he didn’t fully understand, Latxe more than tolerated his presence, she seemed to actually enjoy talking with him. He wondered what if. What if he were stuck in this bubble for the rest of his life? What if Maite didn’t make it? Would he and Latxe…?

He shook his head to clear his thoughts. “Ez,” he said to himself. “Maite is going to be ok and we are going to get that zatia.” He turned to Latxe.

“And you can control the nanobots?”

“Somewhat,” replied Latxe. “Like you saw with the door, we can hijack them in a short radius, but we can’t control too large of a swarm nor can we control them for too long. They have too many security protocols for us to control them for very long. If the rest of the swarm detects odd behavior, they alert the central AI and then destroy the bad nanobots.”

“Central AI?” asked Kepa, his face betraying his ignorance. “What’s that?”

Latxe laughed. “I really don’t know where Olatz found you,” she said. “You really know nothing about the way the world works.”

“Like you said, I’ve been stuck in the United States…” began Kepa.

“You don’t have to repeat that bullshit with me,” interrupted Latxe. “I made that up to cover for you. I know you didn’t spend any time out there. But I can’t figure out where you did come from. You are just so different from anyone I’ve ever met before.”

“I hope that’s a good thing,” said Kepa.

“Oh, I like my men exotic,” said Latxe with a smile.

Kepa blushed. It was too easy to like Latxe.

“Anyways,” he said, changing the subject, “what about the central AI? What does it do?”

Latxe sighed, realizing Kepa was avoiding her obvious flirting. “All of this…” she swept her hand across the horizon “…is too complex for any human to even comprehend, much less understand. So, it is all controlled by the central AI. The Garuna, we call it. The Brain. The Garuna is constantly monitoring the city, determining where new structures are needed, which structures are obsolete, and directing the nanobots where they are needed. The nanobots are like a massive swarm of invisible ants that are always on the move. But, they don’t have a brain. That’s where the Garuna comes in.”

“The nanobots are literally everywhere?” asked Kepa with a shudder.

“Bai. Notice there is no garbage on the ground? The nanobots take care of that. They even remove any dead animals, essentially dissolving them into raw materials that they can use to build.”

“The buildings are made of dead animals?” asked Kepa in disgust.

Latxe laughed. “I guess. I neve quite thought about it like that. But, not just animal matter, but everything. They mine the region around us, again at the direction of the Garuna so that the ground remains stable. They get raw material from everywhere, including our waste.”

“Doesn’t that take a huge amount of energy?” asked Kepa. “Where do you get all of the energy from?”

“Well, the nanobots themselves are powered off of solar energy. They are nearly perfect solar absorbers. But the AI takes a huge amount of energy, that’s true. A fusion reactor powers it.”

“Fusion?” asked Kepa incredulously. “Really? I thought that would never work. I thought it was just an excuse for scientists to chase money.”

Latxe gave him a puzzled look. “Fusion energy was mastered over one hundred years ago. Everyone knows that.”

Kepa didn’t say anything and instead turned his gaze back to the tower.

If you get this post via email, the return-to address goes no where, so please write blas@buber.net if you want to get in touch with me.

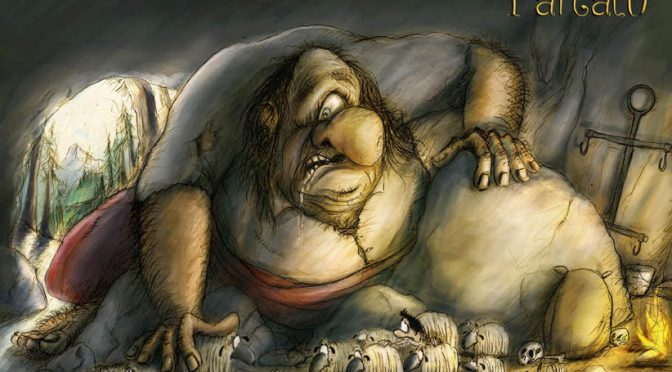

“And saying that, he [the Tartalo] grabbed the elder brother, put him on the side of a roasting fork, and stuck him on the fire, then he ate the elder brother in front of the horrified eyes of the younger.” The Tartalo, the Basque cyclops, was by no means friendly. As opposed to other mythological beings who, in the right context, might aid humans, the Tartalo was always nasty and evil.

Primary source: Hartsuaga Uranga, Juan Inazio. Tártalo. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/tartalo/ar-139122/