This article originally appeared in Spanish at Euskalkultura.eus on March 7, 2022.

Joining the worldwide commemoration of Women’s Day, our colleagues from the historical research group of the Sancho de Beurko Association published another new and interesting article, on another little-known topic, the Nurse Cadets Corps of the United States and the participation of Basque-American women in the Corps. This work represents a new contribution, not only for the studious people of our diaspora, but also in the context of the United States and the vindication of the few members of that group who survive, their pending recognition as war veterans, and in anticipation of the 80th anniversary of the Corps’ creation, to be commemorated in 2023.

ON JULY 1, 1943, in the midst of World War II, the United States Cadet Nurse Corps was created and financed by the United States Congress to train a large number of nurses quickly and efficiently, in order to reverse the situation caused by the serious shortage of nurses both abroad and at home. One in four experienced nurses (about 60,000) had voluntarily enlisted in the Armed Forces.

However, this shortage was not something new since the problem existed before the US entered the war. In fact, the federal government had partially funded the education of 12,000 students in 1941 and 1942, following the recommendations of the Nursing Council for National Defense, established in July 1940. But this was not enough. The demand for nurses by the Armed Forces continued during 1943 at the rate of 2,500 each month [1,2].

Under the command of the United States Public Health Service – a militarized service during WWII – the Cadet Nurse Corps tried to solve this pressing problem via a global approach.

Commitment to perform service with honor during the war

The Cadet Nurse Corps accepted more than 86% of the existing nursing schools to participate “in the first accelerated nursing education programs in the country” [3] in exchange for a series of compensatory aid and subsidies that covered tuition and other student fees. These students, in turn, received a monthly stipend according to their rank (Pre-Cadet, Cadet and Senior Cadet), free room and board, and military-style uniforms and berets (grey in color) with their own rank symbols and insignia. The Nurse Corps also provided postgraduate scholarships, which increased the number of women attending universities. In exchange, the cadets promised to perform their service with honor during the war.

The plan to address the nursing deficit focused on providing substitute care by female students in both civilian and military hospitals across the country, while graduating cadets were given the option of joining their respective nursing corps in the Army and Navy.

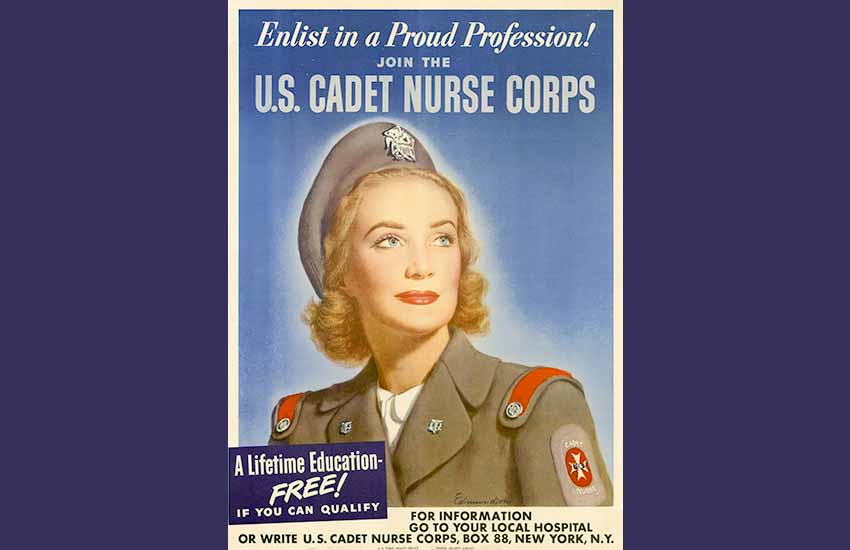

The initial goal of recruiting about 10% of female high school graduates (about 65,000 young women) for the program’s first year in 1943 was quickly exceeded. In fact, any woman between the ages of 17 and 35 with at least a high school diploma could apply to join the Cadet Nurse Corps. This was due, in part, to the success of the recruitment drives. Slogans such as “The girl with a future,” “A lifetime education Free!” or “Enlist in a proud profession!” attracted a wide range of women from different socioeconomic backgrounds “without discriminating on the basis of race, creed, or color” [4]. The goal of recruiting additional nursing students for the next two years (65,000 for 1944 and 60,000 for 1945) was also met. A total of almost 180,000 women applied to join the Corps.

During the last six months of their training, Senior Cadets were required to work 48 hours a week on active duty, in military, government, or civilian hospitals, under supervision and assuming the same duties as a registered nurse. Most of them served in non-federal hospitals (mainly the hospitals where the cadet was trained), federal hospitals (mainly the Veterans Administration), and military hospitals. After completing this last stage, the cadet nurses received their diploma from the nursing school where they had started their training.

The positive impact of the Cadet Nurse Corps was unquestioned. In 1945, 85% of the country’s nursing students were nurse cadets, and about 80% of the hospitals were served by them during and immediately after the war, replacing the nurses who joined the Armed Forces. In conclusion, it prevented the collapse of nursing care in hospitals. In January 1945, US Surgeon General Thomas Parran, Jr. testified before the House Committee on Military Affairs, stating: “In my opinion, the country has received and increasingly will receive substantial returns on this investment. We can not measure what the loss to the country would have been if civilian nursing service had collapsed, any more than we could measure the cost of failure at the Normandy beachheads” [5].

Basque veterans of the Cadet Nursing Corps

As a national program, the Cadet Nurse Corps had a presence in all states. In this article we present the unpublished stories of seven cadet nurses of Basque origin from five states – California, Montana, Nevada, New York and Wyoming – that can help us understand the importance of the Corps in the personal and professional development of its members and in the patriotic involvement, at an early age, of the first Basque generation born or raised in the US.

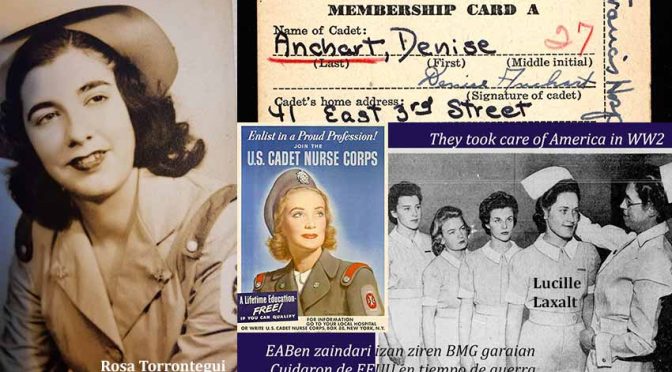

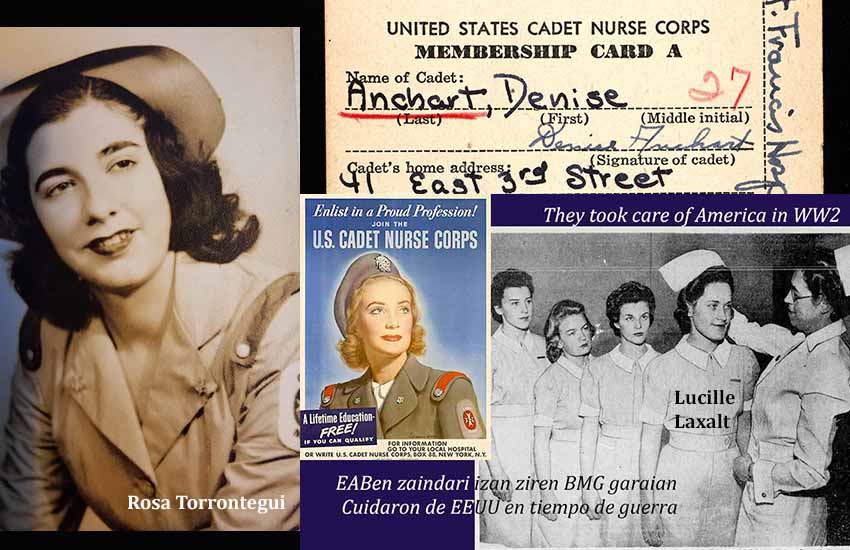

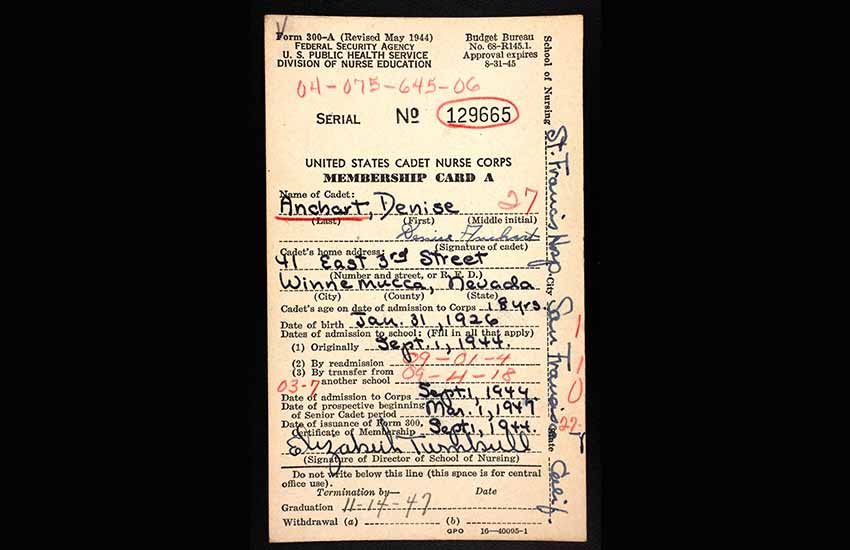

Six of the Cadets were born in the United States. They are Denise Anchart (Anchartechahar) Mon (born 1926 in Winnemucca, Nevada), Genevieve Mary Caricaburu (Carricaburu) Ader (1927, Glasgow, Montana), Mary Jean Etcheverry Mendiola (1921, Border Junction, Wyoming), Lucille Catherine Laxalt Ucarriet (1921, Alturas, California), Rosa Torrontegui Olondo (1924, New York), and Laura Ugarriza Sarrionandia (1926, McDermitt, Nevada).

In addition, we have been able to identify the first woman born in Euskadi to enlist in the Cadet Nurse Corps: María Josefa “Mary Josephine” Alcorta Larrañaga, born in 1927, in Bilbao, Bizkaia, but raised since she was a baby in Indian Valley, California, and later in Winnemucca, Nevada.

All of our Basque veterans of the Cadet Nurse Corps were young women between the ages of 17 and 22 at the time of their enrollment. All of them came from small rural towns – except Torrontegui who grew up in the City of Skyscrapers – and had parents that had dedicated themselves to a great extent to farming and ranching, hospitality, construction, or mining.

Only Laxalt and Etcheverry began their nursing careers before the creation of the Cadet Nurse Corps and even before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

On August 19, 1941, Lucille Catherine Laxalt Ucarriet, born to parents from Zuberoa and Nafarroa Beherea, was admitted to the Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, California, to train as a nurse. She was followed by Mary Jean Etcheverry Mendiola, born to parents from Nafarroa Beherea and Bizkaia, who enrolled in the Holy Cross Hospital School of Nursing, in Salt Lake City, Utah, on September 9, 1941. While in training school, Laxalt, 22, was admitted to the Cadet Nurse Corps on July 1, 1943, the date of its creation. She graduated on March 20, 1944. Later, Laxalt successfully passed the State Board’s rigorous exam to become a Registered Nurse, a fundamental requirement to start her working life.

Like Laxalt, Etcheverry also became part of the Cadet Nurse Corps, at the age of 21, at the time of its creation. She was one of approximately 120 Wyoming cadets who served in the Corps. Etcheverry graduated from nursing school on September 14, 1944, being sent to Madigan General Hospital/Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Washington. It was there that she met her future husband, Normandy D-Day veteran Clarence Edward Vote (1911, Minot, North Dakota). Seriously injured, Vote spent four years of his life recovering in the hospital. Although cadets weren’t supposed to fraternize with soldiers, they found a way to get to know each other. Etcheverry was honorably discharged with the rank of second lieutenant on June 9, 1948, as part of the Army Nurse Corps, which she had joined upon her graduation as a cadet. Four months later, on October 16, 1948, she married Vote.

On the east coast, 18-year-old Rosa Torrontegui Olondo, born to Bizkaian parents, also joined the Cadet Nurse Corps in 1943, just one month after its formation, being admitted to Bellevue Nursing School, New York, on August 12. Torrontegui graduated on October 12, 1946. As her daughter, Patricia Oleaga, told us, “She was expected to serve in the war, but the war ended just when she graduated from nursing school.” A year after her graduation, Torrontegui married her Basque compatriot, WWII veteran Feliciano “Félix” Oleaga Garayo (Mundaka, Bizkaia, December 13, 1921) in New York.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

The Torronteguis, leaders of the New York Eusko Etxea

When Patricia was young, her mother went back to work as a nurse and then as a pediatrics instructor at the Queens General School of Nursing until it closed. She completed her bachelor’s degree from the City University of New York in Queens and her master’s degree at C.W. Post at Long Island University. She continued to work in Manhattan at Gouverneur Hospital as a charge nurse and returned to Queens General as their nurse epidemiologist just as New York City was hit by a virus, totally unknown at the time, and later known as AIDS. She worked as an epidemiologist until she retired. Both Rose and her husband were very active in the hundred-year-old Basque association in New York, Euzko-Etxea: he becoming president of it and she the president of the Andrak women’s group.

Back in the American West, after graduating from Glasgow High School, Montana, Genevieve Mary Caricaburu Ader joined the Cadet Nurse Corps on September 25, 1944, training at the Columbus Hospital School of Nursing in Great Falls, Montana. Born to parents from Nafarroa Beherea and Lapurdi, Caricaburu was one of approximately 1,770 Montana women who joined the corps. She was just 17 years old, the second youngest in our group of Basque veterans.

Caricaburu graduated in February 1947. A month later, she began studying psychiatric nursing at the Montana State College of Nursing in Warm Springs, later working at the Veterans Hospital in Lincoln, Nebraska. At the end of that year, Genevieve married WWII veteran Lawrence Frank Kotecki (1924, Thorp, Wisconsin) in Lincoln. Upon her death at the age of 81, she was buried at Fort Logan National Cemetery in Denver, Colorado, alongside her husband, not on her own merits during the war, but because she was the wife of a veteran. Today, as we will see later, the associations related to the Cadet Nurse Corps have made the right to be buried in a military cemetery a central part of their banner of struggle.

The three remaining Basques – Alcorta, Anchart, and Ugarriza – joined the Cadet Nurse Corps after graduating from Humboldt High School in Winnemucca in May 1944. Two more girls out of a total of 40 young women from the same class also joined. They were Emile Germanine Bellon and Iva May Quilici. All of them were admitted in early September 1944 and graduated between September and November 1947.

A patriotic commitment

“Probably if the war hadn’t come along I know my father expected me to go to the University of Nevada,” Denise Anchart (Anchartechahar) Mon confessed. “But all the boys were going into the service […] the boys were doing their patriotic thing and we thought we should […] and if you look at our year book it’s the skimpiest one in the library, and the girls thought, ‘Well what are we going to do?’ So they had the Cadet Nurse Corps and quite a few from Winnemucca did go. Let’s see, five of us went the year I went,” recalled Anchart [6].

At just 17 years old and the youngest of our Basque cadets, María Josefa “Mary” Alcorta Larrañaga, began her training at Mercy Hospital Nursing College in Sacramento, California, while Anchart began hers at St. Francis Hospital in San Francisco. Laura Ugarriza Sarrionandia, whose parents were from Bizkaia, was admitted to St. Luke’s Hospital, also in San Francisco. After the war, Ugarriza continued her nursing career and studied Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Fortunately the war ended soon,” Anchart said, relieved. The Nurse Cadet Corps “was a three-year hospital program, and the war did end in three years… If the war hadn’t ended – the government paid for my education, my obligation was to go in the service as an officer,” Anchart explained. At the time of their induction, each nurse cadet had to take an oath, part of which reads: “I am solemnly aware of the obligations I assume toward my country and toward my chosen profession; […] As a Cadet Nurse, I pledge to my country my service in essential nursing for the duration of the war.” She concluded “I did have a choice as to whether I wanted to go in the Army or whether I wanted to go in the Navy. And we thought about it all the time. Fortunately, I was in San Francisco VE Day, and VJ Day” [6].

Towards the honorary status of war veterans

Cadets in gray are here to carry along

The valiant fight to keep America strong!We’re the Cadets,

We’re in the Corps,

Doing our part to help the nation win the war,

Doing the job we’re chosen for,

United States Cadet Nurse Corps(Stanza of the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps March by Beatrice and Edmund Ziman, 1944.)

Approximately 124,000 nurse cadets were trained during the course of the war. The Nurse Cadet Corps became the largest and youngest group of uniformed women to serve their country. Admission to the Corps – a time-honored service for the duration of the war – stopped two months after Japan’s surrender. However, the Corps remained active until 1948, completing the training of over 116,000 cadets and caring for wounded soldiers on their return to military hospitals.

Only uniformed Corps without veteran status

In addition to the tens of thousands of nurse cadets, another 350,000 American women served as volunteers in the “auxiliary” military corps created ad hoc at the beginning of the war and assigned to different military branches, serving both at home and abroad.

These new military corps (Women’s Army Corps, Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service, and Women Air Force Service Pilots) joined the traditional Army and Navy nursing corps, which numbered a large number of women, many of them cadets. With the exception of the Women Air Force Service Pilots, who did not receive veteran status until 1977, the rest of the “auxiliary” corps received full military status and thus enjoyed post-war benefits.

In contrast, upon discharge, members of the Cadet Nurse Corps did not receive veteran status nor the benefits associated with it.

At the time of this writing, nurse cadets are the only members of all uniformed corps that served in WWII who have not yet been recognized as veterans by the US Congress. Several bills have been introduced in Congress to rectify this injustice, but so far all have failed.

As Barbara Poremba, founder of Friends of U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps WWII, comments “These women of the Greatest Generation only request to be honored as Veterans of WWII with an American flag and a gravesite plaque forever marking their proud service to our country during wartime in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps” [7].

The year 2023 will mark the 80th anniversary of the creation of the US Nurse Cadet Corps. Wouldn’t it be fair to recognize the service performed by the nurse cadets during the WWII? What better way to do this than by granting its members honorary veteran status. From Sancho de Beurko and the “Fighting Basques” research team we believe so and we fully support the initiative.

If you know a cadet nurse of Basque origin, you can write to us at sanchobeurko@gmail.com.

Sources

American Nurses Association, Inc./Foundation. “50th Anniversary: 1944-1994: Enlist in a Proud Profession! Join the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps.” Part 1 and Part 2.

Anchart, Denise and Andrée, “The Anchart Family Oral History,” by Linda Dufurrena. 1993. Humboldt County Library Oral History Project. Nevada Library Cooperative.

“A Salute to the Cadet Nurse Corps: Commemorating Fifty Years of Service.”

“Information Program for the United States Cadet Nurse Corps.” Prepared by the Office of Program Coordination, Office of War Information, in cooperation with U.S. Public Health Service, Federal Security Agency. September 1943.

Poremba, Barbara. “Celebrating the 75th Anniversary of the Establishment of the US Cadet Nurse Corps of 1943”.

The USCadetNurse.org Foundation.

Turk, Marilyn. “The United States Cadet Nurse Corps.” April 22, 2017. Heroes, Heroines and History.

Willever-Farr, Heather and John Parascandola. “The Cadet Nurse Corps, 1943-48.” Public Health Reports, Vol. 109 (May-June 1994): 455-457.

References

[1] Turk

[2] American Nurses Association

[3] Poremba

[4] “A Salute to the Cadet Nurse Corps…”

[5] Poremba

[6] Anchart, Denise and Andrée… Pp. 43-45.

[7] Poremba

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”