I’ve known Argia Beristain for about 20 years now, having first met her during our joint activities in the Seattle Euskal Etxea. She has since moved back and forth between the two coasts of the United States and has been extremely active in promoting Basque culture, culminating in the Basque Soccer Friendly that was held in Boise, Idaho this past summer.

I’ve known Argia Beristain for about 20 years now, having first met her during our joint activities in the Seattle Euskal Etxea. She has since moved back and forth between the two coasts of the United States and has been extremely active in promoting Basque culture, culminating in the Basque Soccer Friendly that was held in Boise, Idaho this past summer.

In this interview, I ask Argia about the planning and organization of the Basque Soccer Friendly, her experiences being part of four very different Basque communities in the United States, and her favorite places in the Basque Country.

Buber’s Basque Page: Last summer (July 18), you saw the culmination of a lot of your blood, sweat and tears over the last year or so in the Basque Soccer Friendly, which brought both Athletic Bilbao and Club Tijuana to Boise to play an exhibition soccer match. What was this experience like? What was the most gratifying part of organizing this amazing event? What challenges surprised you the most?

Argia Beristain: The experience of planning, organizing and executing the Basque Soccer Friendly was an exhausting emotional roller coaster. There were so many times along the way that new obstacles were placed in front of us and many thought “oh there’s no way they can overcome this” and we refused to give up and somehow overcame each and every one of them. You can call it tenacity or stubbornness I guess but it was a passion of mine to make sure that I personally tried everything I could to make it a reality. We had worked so hard, I knew I would never forgive myself for turning back and not doing absolutely everything I could think of to keep the project moving forward.

The most gratifying part of organizing this amazing event has to be seeing how so many people’s dreams came true, not only my own or my Aita’s which was personally motivating all along the way. The overall feeling/vibe on the Basque Block and at the game was pure happiness — it’s so great to know I helped bring that happiness to the community. To point to one specific moment though, it would have to be when I saw an interview my husband, Keegan, did with the local newspaper that was recorded and posted online after Athletic Club’s arrival in Boise. I could not have done any of the work on this without his endless support, he held me up and gave me encouragement every single step of the way. But at that moment, seeing his own personal excitement and satisfaction that all of our hard work had paid off and that our team was actually arriving in Boise, Idaho thousands of miles away from the Basque Country was beyond gratifying.

The most gratifying part of organizing this amazing event has to be seeing how so many people’s dreams came true, not only my own or my Aita’s which was personally motivating all along the way. The overall feeling/vibe on the Basque Block and at the game was pure happiness — it’s so great to know I helped bring that happiness to the community. To point to one specific moment though, it would have to be when I saw an interview my husband, Keegan, did with the local newspaper that was recorded and posted online after Athletic Club’s arrival in Boise. I could not have done any of the work on this without his endless support, he held me up and gave me encouragement every single step of the way. But at that moment, seeing his own personal excitement and satisfaction that all of our hard work had paid off and that our team was actually arriving in Boise, Idaho thousands of miles away from the Basque Country was beyond gratifying.

Of all the challenges that surprised me throughout the process, the most staggering element is just how expensive putting on an event like this really is. Even with Athletic Club waiving their appearance fee, the cost of Tijuana’s appearance fee, flying both teams to Boise, hotels, food, transportation, on top of all of the expenses associated with use of Albertsons Stadium, signage and the major budget needed for the installation of the sod, it all adds up very quickly. That doesn’t even include marketing or merchandise which we had committees of amazing volunteers dedicating hundreds of hours to in-kind. We all knew it was going be expensive and, quite honestly, our budget projections from a year ago are not that far off, but when you step back and look at everything including all of the “in-kind” our sponsors gave us to support the game, it’s truly staggering how much money is needed to pull this thing off.

Buber’s Basque Page: What was the history of this project? When did it first get discussed? Who else had been involved in bringing this event from the concept stage to final fruition?

Argia Beristain: This history of this project starts at Jaialdi 2010 with Mayor Dave Bieter, John Bieter, and representatives from the Province of Bizkaia enjoying a nice dinner and a good amount of wine while dreaming up ways to make Jaialdi “even bigger next time”. Their conversation started focusing in on sports and ultimately it was suggested that a team from the Basque Country should come and play a game in Boise. Then a couple years later, John Bieter pulled together some people on the Boise State campus to see if they agreed it was a good idea in April 2013. That June, I moved to Boise and even before my furniture arrived, I received a call from Dave Lachiondo, Associate Director for Basque Studies at Boise State, asking me if I wanted to be involved since my background was in non-profit fundraising and we’d inevitably need to raise quite a bit of money to make this possible. From that point we formed a small committee and people joined and left the committee at various stages based upon our needs for the next year or so.

Eventually, at the core there was John Bieter (Basque Studies), Bill Taylor (Idaho Youth Soccer Association) and myself as Directors to lead the way. I worked hand-in-hand with Bill Taylor on all things soccer related (teams, FIFA Agents, equipment, field, etc.) then for all things sponsor and donor related, John and I worked together. We were quite the team. All along John was there to ride the up and downs of this event with me every step of the way. It helped that we could also go and meet with Mayor Dave Bieter when we needed some additional help opening doors along the way.

Eventually, at the core there was John Bieter (Basque Studies), Bill Taylor (Idaho Youth Soccer Association) and myself as Directors to lead the way. I worked hand-in-hand with Bill Taylor on all things soccer related (teams, FIFA Agents, equipment, field, etc.) then for all things sponsor and donor related, John and I worked together. We were quite the team. All along John was there to ride the up and downs of this event with me every step of the way. It helped that we could also go and meet with Mayor Dave Bieter when we needed some additional help opening doors along the way.

Along the way we found an amazing designer, Paul Carew, and other marketing professionals like Jason Hamilton who helped steer us in right direction. By January 2015, we formed a volunteer marketing committee that met weekly with Paul (all things brand related, logos, signage, merchandise, etc.), Jason Hamilton (managed our tv commercials and relationship with hispanic tv and our media partner, KTVB), Drew Lorona (social media and email campaigns), Ana Overgaard (production of videos as needed), Keegan Dougherty (website, live stream, online store and retail space manager) and myself. It was a fun but small group of amazing individuals who all wanted to see the game happen and be the best event it could be. I joked at one point that I was going to stop coming to marketing meetings because I always left there with a lot more work to do. But all kidding aside, they were awesome and the event’s success can be attributed directly to them. When you step back and think about how volunteers pulled off this major event, it’s inspiring.

Another major person behind the scenes for the Basque Soccer Friendly was Fred Mack of Holland & Hart, our legal team. An event like this requires very detailed team, vendor and sponsor contracts, as well as an elaborate agreement with Boise State University. Fred joined our team “pro bono” in March 2015 and suddenly everything started moving much more smoothly.

Add to that our Volunteer Director Daniel Brunham and the numerous amazing volunteers that he coordinated to support our events leading up to the game, retail store and install/removal of the field and it’s clear to see it took quite a team.

On the Basque Studies side, we also could not have done it without John Ysursa. He was there to support John Bieter, Keegan and I with anything we needed help with from painting the retail location walls, filling shifts as “Johnny Retail”, installing/removing the sod, storing our merchandise, you name it. Whenever we needed anything, we always knew we could count on Y.

All in all, it was a small group of individuals committed to making this game a success. Some of us have been on the team for 2 years, most 6-9 months but at the end of the day, we all gave endless hours that in my opinion paid off by a successful event.

Buber’s Basque Page: Originally, the Basque Soccer Friendly was going to be during the same week as Jaialdi, but it got moved due to Athletic Bilbao’s making it to the Europa League competition. I heard more than one person say that, in the end, this was a good thing as dealing with the sod during Jaialdi would have been a nightmare. How did you feel about the change in time?

Buber’s Basque Page: Originally, the Basque Soccer Friendly was going to be during the same week as Jaialdi, but it got moved due to Athletic Bilbao’s making it to the Europa League competition. I heard more than one person say that, in the end, this was a good thing as dealing with the sod during Jaialdi would have been a nightmare. How did you feel about the change in time?

Argia Beristain: Moving the date of the game was the last thing we wanted to do but, in the end, we know everything happens for a reason and for this first time event we can honestly say we think it worked out best this way. There are countless stories of friends, family and soccer fans from throughout the United States, Mexico and the Basque Country who had plans to come to the game on the 29th during the week of Jaialdi who were not able to go with the date change to the 18th. We can’t help but think that we would have had a lot more than 22,000 in the Stadium if it had been during Jaialdi; however, from the logistics and event experience for Athletic Club Bilbao’s side of things, it was definitely better off on the 18th.

For example, logistically no one in Boise had ever been through the process of installing the sod over turf and we relied heavily upon our volunteers to help with the plastic event decking and tarp installation and removal portions of that process. That equaled a lot of hours of hard work and it was hard enough to find enough dedicated volunteers who were willing to pitch in. If it had been during Jaialdi when many of the local Basque community is already busy putting on the various Jaialdi events, it would have been even more difficult to accomplish this major volunteer effort that took multiple days of physical labor. Another logistical issue beyond the already full hotels throughout Boise during Jaialdi is the busses that were needed for the teams. With the demand for busses that Jaialdi puts on the local community with shuttles from hotels, performer shuttles, etc., I don’t think there are physically enough busses in the greater Treasure Valley area to meet the needs of Jaialdi and the soccer teams at the same time.

Then, as for Athletic Club’s experience and our community’s access to the team, I don’t think they would have been able to have the freedom to visit the Basque Block, the Basque Museum and the Basque Center, Basque Soccer Friendly store and have autograph signings as they were able to if it had been during Jaialdi. With the game on the 18th, they were able to spend the entire afternoon on the 17th playing Pala in the Fronton, checking out the museum and boarding house, enjoying a meal at the Basque Center, playing FIFA at the Basque Soccer Friendly store and visiting the Ikastola. The team gave the Boise community unprecedented access by making all players available for autographs so we split them into groups at the Basque Center, the Basque Soccer Friendly store and the Ikastola. Each location had lines around the block with Basques and non-Basques alike eager to meet them and get their autographs. They were so gracious and stayed until they signed for everyone which gave them a real opportunity to meet the Basque diaspora and greater Boise community which resulted in so many dreams made true. Now, if it had been during Jaialdi, they would have seen even larger crowds on the Block and a lot more in the Stadium I’m sure, however they would have been mobbed and we would not have been able to have the autograph signings and they would not have had the freedom to explore the Basque Block or visit with distant family like they did.

Buber’s Basque Page: You’ve now been part of Basque communities in Seattle, Washington DC, and Boise, and grew up in the Las Vegas Basque community. What do you see as the big differences in these different clubs/communities and the commonalities?

Argia Beristain: Wow, that’s a good question. My experiences working in support of the Basque Communities in Las Vegas, Seattle, Washington, DC and now Boise have all been very different and are dependent upon the demographics of the communities, yet it always comes down to a few dedicated volunteers who are willing to give so much of themselves to keep the clubs or projects going.

In Las Vegas, our biggest challenge is that the original Basque immigrants who started the Lagun Onak Las Vegas Basque Club are getting older and unable to sustain the club forever. The heart of the club at the beginning and today are the pelotaris or Jai Alai players who used to play professionally on the Las Vegas Strip until 1980 when the casinos closed the frontons. At that time many of the players stayed to become card dealers for the casinos and what was originally a group of Jai Alai friends became an organized Basque Club in 1980. This however was the last major immigration of Basques to the Las Vegas valley and many of the children of these pelotaris and dedicated Basques are either not interested in maintaining or preserving their Basque Culture or they have moved away. As a result, as the founders of the Basque Club enter their 70s it’s difficult for them that all of the activities of the club and organization of the events fall solely upon their shoulders.

In Seattle, as you know, there isn’t quite that distinct time that you can point to when most of the Basque immigrants came to the area. Instead, the major hurdle that I see for the Seattle Basque Community is just how vast the area is and how spread out all of the Basques are. In this continuously evolving cultural society there are many demands on us as individuals and families from social engagements to soccer practice, dance classes, etc. — it’s helpful if the Basque component is convenient too, which isn’t always possible for all of the Basques throughout Washington.

Now Washington, DC is completely different as the majority of our members are in their 30s and 40s yet were born in the Basque Country and are in DC working for maybe only a few years. A few of the Basque Americans who have grown up in Boise, Elko, Chicago, etc. have moved there too and are members of the club however the biggest hurdle is conveying the need or necessity to preserve or celebrate our Basque Culture to those who “being Basque” is compulsory because they grew up in the Basque Country and thats just how they lived. It’s interesting to note that of the 5 current Board of Directors for the Washington, DC Euskal Etxea, 4 of us are Basque Americans and there is just 1 who was born in the Basque Country yet our membership base is heavily Basque Country born. Now, at different times we have had other Basque Country born Board members but as the club gets older and faces more challenges, it appears the Basque Americans who have grown up in other Basque Diaspora communities are the ones pushing the hardest to keep it going in DC.

Then there’s Boise. I think the best thing going for the Boise Basque Community is it’s numbers and the sheer volume of Basques that have immigrated to Idaho throughout the years. With there being so many generations of Basques and Basque Americans who have grown up celebrating Basque culture and having Basque culture celebrated by the greater Boise community it makes it, in my opinion, easier to perpetuate. It’s cool to be Basque in Boise. At the end of the day, the work and responsibility still only falls on a few dedicated volunteers no matter where you live; however, with such a large population to pull from in Boise/Treasure Valley, you’re more likely to find those people willing to help. Furthermore, the burden placed upon one person is less when there are more people willing to teach euskal dantza, euskera, mus, briska, movie night, etc. and one when one person gets tired, overwhelmed or needs to handle the soccer practice car pool instead, there is more of a chance to find someone else in the Basque community to pick up where they left off rather than the effort halting completely.

Then there’s Boise. I think the best thing going for the Boise Basque Community is it’s numbers and the sheer volume of Basques that have immigrated to Idaho throughout the years. With there being so many generations of Basques and Basque Americans who have grown up celebrating Basque culture and having Basque culture celebrated by the greater Boise community it makes it, in my opinion, easier to perpetuate. It’s cool to be Basque in Boise. At the end of the day, the work and responsibility still only falls on a few dedicated volunteers no matter where you live; however, with such a large population to pull from in Boise/Treasure Valley, you’re more likely to find those people willing to help. Furthermore, the burden placed upon one person is less when there are more people willing to teach euskal dantza, euskera, mus, briska, movie night, etc. and one when one person gets tired, overwhelmed or needs to handle the soccer practice car pool instead, there is more of a chance to find someone else in the Basque community to pick up where they left off rather than the effort halting completely.

I wouldn’t trade my experiences in any of the communities for anything and I think that what it means to me to be “Basque” and the type of volunteer that I am today is a result of all of the experiences I’ve had in these various Basque communities.

Buber’s Basque Page: The next big event in Basque cultural space in the US looks to be the 2016 Folklife Festival, put on by the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. I understand you were involved in making this event happen. What can you tell us about the event?

Argia Beristain: Yes, I’m very excited about the Smithsonian Folklife Festival that will present Basque Culture on the National Mall in DC in June/July 2016. Mark Bieter and I have been meeting with the folks from the Smithsonian since 2006 to make this dream come true. With the help of the Basque Government’s Aitor Sotes and more recently Ander Caballero and the recent addition of the representatives from the Province of Bizkaia, it’s finally happening!

Every summer the Smithsonian presents a living museum featuring cultures from around the world and 2016 is the 50th Anniversary of the festival. The Washington, DC Euskal Etxea is helping connect the Smithsonian with local vendors and contacts to have authentic Basque food, cider, wine and more. Most of the performers will probably come from the Basque Country but it’s expected that a number of them will be from the Basque American Diaspora as well. The Smithsonian team is working directly with NABO on that selection process as we speak. It’s exciting stuff! I hope Basque Americans make an effort to get to DC this summer to see it, it’s sure to be a once in a lifetime moment for our culture and language.

Buber’s Basque Page: Now, a few questions about the Basque Country itself. What is your favorite spot in the Basque Country?

Argia Beristain: My favorite place in the Basque Country is Ondarru (Ondarroa). Specifically the port and beach area. I have fond memories of waking up early as little kid and sitting on my Amama’s patio to watch the fishing boats come in during the early morning. As I got older, I’ve enjoyed sitting at Moby Dick enjoying a txikito with my kuadrilla along the beach. Ondarru is so beautiful and the people are uniquely Ondarrutarra. I love that.

Buber’s Basque Page: What is your favorite Basque food?

Argia Beristain: My favorite Basque food would be comfort food my family makes. Like my Itxiko Miren’s zapu (fish) or her soup. My aita’s paella or when he makes tongue (only ever in a red sauce). Once while I was living in DC and pregnant and unable to travel to visit family, I asked my aita to ship me some of his paella (frozen of course) and his tortilla patata. I’ve never received a gift that made me feel so comforted and close to family even though I was 2,500 miles away from all of them in Las Vegas and 3,800 miles away from Ondarru.

Buber’s Basque Page: What is your favorite Basque fiesta?

Argia Beristain: My favorite fiesta is Ondarruko Jaixak in August celebrating Andra Mari but a close second would be Madalenas in Elantxobe, Bermeo…..

Buber’s Basque Page: Finally, is there anything else you would like to add?

Argia Beristain: As it’s been a few months now since the game in July, I’ve had some time to reflect on just how amazing it is that it all came together and we actually brought Athletic Club Bilbao to Boise, Idaho! On top of that, we covered the iconic blue turf at Boise State University and introduced high level professional soccer/futbol to a traditionally American Football community. Lastly, even though we had to move the game away from Jaialdi and lost a lot of the Basque community’s ability to attend, we still had 22,000 people fill the stadium. It’s amazing to me when I stop and reflect on all of that. I’m proud of the fact that we pulled it off and it was a great success.

Argia Beristain: As it’s been a few months now since the game in July, I’ve had some time to reflect on just how amazing it is that it all came together and we actually brought Athletic Club Bilbao to Boise, Idaho! On top of that, we covered the iconic blue turf at Boise State University and introduced high level professional soccer/futbol to a traditionally American Football community. Lastly, even though we had to move the game away from Jaialdi and lost a lot of the Basque community’s ability to attend, we still had 22,000 people fill the stadium. It’s amazing to me when I stop and reflect on all of that. I’m proud of the fact that we pulled it off and it was a great success.

The Basque Soccer Friendly is truly a testament to remaining positive, not giving up and doing whatever it takes to reach a dream/goal. I hope to have more opportunities to pour myself into a project like this in the future.

Buber’s Basque Page: Eskerrik asko Argia!

Share this / Partekatu hau:

Like this:

Like Loading...

Vince Juaristi, a native of Elko, Nevada and author of Back to Bizkaia, was asked by the Smithsonian to write a series of articles that highlight how the Basques have crossed paths with the United States throughout the years.

Vince Juaristi, a native of Elko, Nevada and author of Back to Bizkaia, was asked by the Smithsonian to write a series of articles that highlight how the Basques have crossed paths with the United States throughout the years. I’ve touched on the connection between the Basques and John Adams, the 2nd president of the United States. In his second article, Intertwined: John Adams encounters the Basques, Vince delves deeper, describing the arduous journey Adams made across Spain, on his way to Paris, and his surprising and revealing encounter with the Basque Country, an experience he would recall with admiration when he was researching governments as the US Constitution was being developed.

I’ve touched on the connection between the Basques and John Adams, the 2nd president of the United States. In his second article, Intertwined: John Adams encounters the Basques, Vince delves deeper, describing the arduous journey Adams made across Spain, on his way to Paris, and his surprising and revealing encounter with the Basque Country, an experience he would recall with admiration when he was researching governments as the US Constitution was being developed.

Anyone who has visited the Basque Country knows how important cheese is to the cuisine of the Basques. Idiazabal might be the most famous, but cheese is everywhere in Euskadi. Meals often end with a plate of cheese and membrillo.

Anyone who has visited the Basque Country knows how important cheese is to the cuisine of the Basques. Idiazabal might be the most famous, but cheese is everywhere in Euskadi. Meals often end with a plate of cheese and membrillo.

Pete – dad – was my inspiration. Like many of you here today, or your parents or grandparents, he gave up everything he knew, everything he grew up with, to build a better life. He came to what must have seemed the most desolate place on earth, especially compared to the vibrant green mountains and fiestas of the Basque Country. He left all of that behind to start a new life, a life that left him the hills around Silver City with nothing more than one fellow sheepherder and a dog to keep him company for months at a time. From this new beginning, he found a new life.

Pete – dad – was my inspiration. Like many of you here today, or your parents or grandparents, he gave up everything he knew, everything he grew up with, to build a better life. He came to what must have seemed the most desolate place on earth, especially compared to the vibrant green mountains and fiestas of the Basque Country. He left all of that behind to start a new life, a life that left him the hills around Silver City with nothing more than one fellow sheepherder and a dog to keep him company for months at a time. From this new beginning, he found a new life.

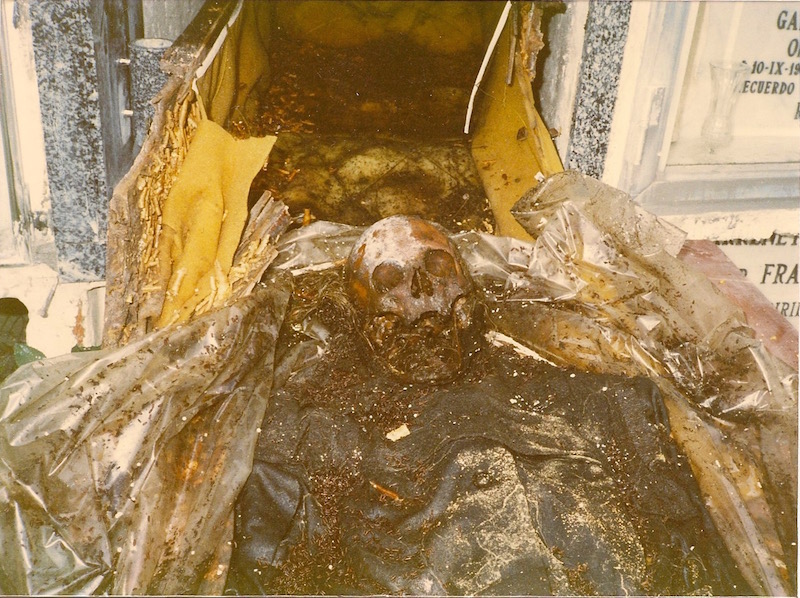

One of the most interesting and surreal experiences I had when I lived in the Basque Country during 1991-92 was when I went with my great uncle to the Gerrikaitz-Arbatzegi emetery. Cemeteries in the Basque Country are not as expansive as they are in the United States.

One of the most interesting and surreal experiences I had when I lived in the Basque Country during 1991-92 was when I went with my great uncle to the Gerrikaitz-Arbatzegi emetery. Cemeteries in the Basque Country are not as expansive as they are in the United States.