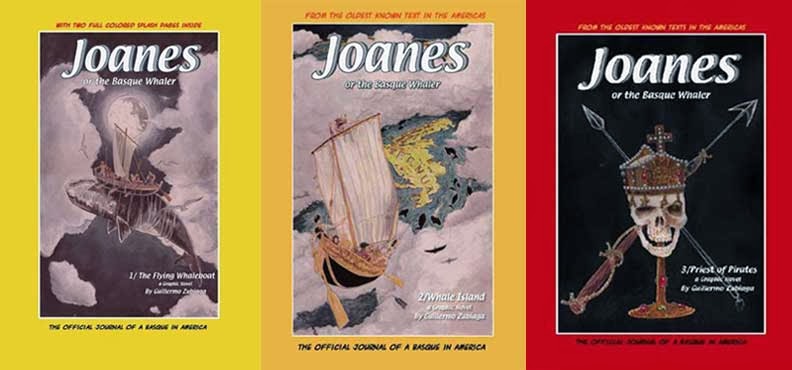

The third and final installment of Guillermo Zubiaga’s epic about Basque whaling, Joanes or the Basque Whaler: Priest of Pirates, follows the final exploits of Guillermo’s hero, Joanes. This graphic novel, based on historical documents of Basque derring-do on the high seas, culminates the grand adventures of Joanes and his crew as they encounter deadly pirates, an even deadlier monster whale, and mythical creatures from Basque myth.

The third and final installment of Guillermo Zubiaga’s epic about Basque whaling, Joanes or the Basque Whaler: Priest of Pirates, follows the final exploits of Guillermo’s hero, Joanes. This graphic novel, based on historical documents of Basque derring-do on the high seas, culminates the grand adventures of Joanes and his crew as they encounter deadly pirates, an even deadlier monster whale, and mythical creatures from Basque myth.

I won’t spoil the story, but suffice it to say it takes Joanes and his crew to the depths of the ocean, to the coasts of New Foundland, and through glacial fields. Along the way, Joanes and the crew encounter a monster killer whale, a lamiak, various Native American tribes, and British and Danish pirates. It is a roller coaster ride that is fast paced and covers a lot of ground and time. Compared to the previous volumes, it felt both grander in scope and thus a bit less action oriented (though there is plenty of action).

As with the previous volumes, there are so many references to history and myth that I really found myself wishing to know more. Guillermo opens the volume with a little bit of background, particularly regarding the skull chalice that graces the cover. I understand that Guillermo is working on collecting the three volumes into one graphic novel (which provides him with an opportunity to correct some mistakes that crept in). I sincerely hope that it is annotated to provide that historical and mythological context the story and art are based upon.

The story is a rowdy jaunt through Basque history that is delightful, both for the art and for the cultural references. I highly recommend it and look forward to the collected volume!

Zorionak Guillermo!