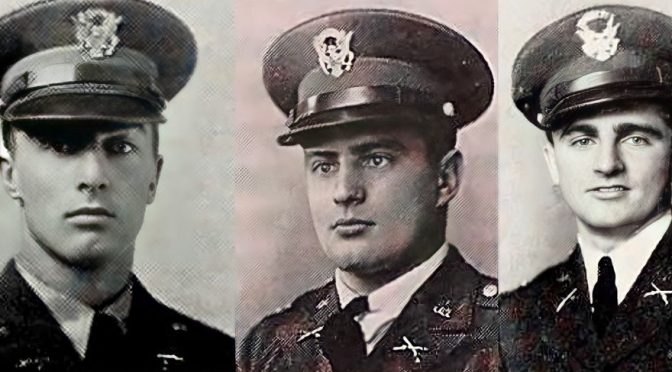

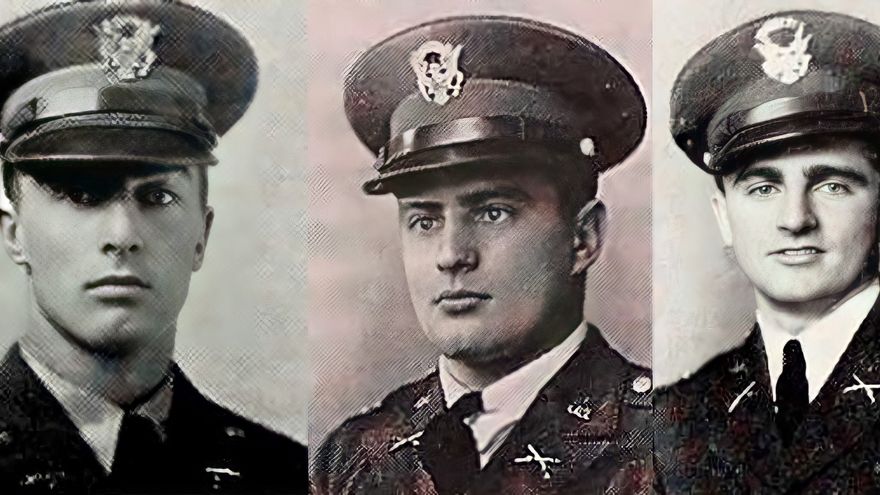

Between them, these three Basque-American brothers had 27 years of military service, a third of them during World War II.

This article originally appeared in its Spanish form in El Diario.

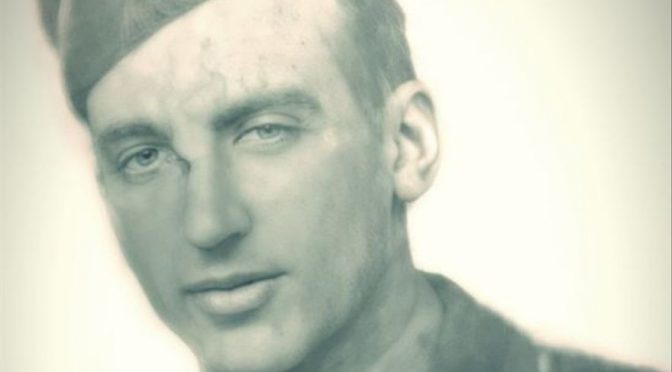

In February 1952, the Reno Gazette-Journal proclaimed the Basque-American brothers John, Leon, and William Etchemendy Trounday as “the most decorated group of brothers in Nevada.” Between the three, they had a combined 27 years of military service – a third of them in combat – having participated in the World War II and the Korean War. In total, they received twelve stars representing each military campaign they participated in – from Normandy to Okinawa, passing the 38th Parallel and the Yalu River – six purple hearts, two presidential commendations, and nine other decorations [1]. They had traveled the world, starting from their hometown of Gardnerville in the State of Nevada. However, the origin of their history dates back a few decades earlier to the small towns of Nafarroa Beherea, Arnegi and Ortzaize [2].

Arnegi, on the road that connects Donibane Garazi and Iruñea, currently has a population of less than 240, half of what it had at the beginning of the 20th century. Similarly, Ortzaize, barely 20 kilometers away from Arnegi, with a population today close to 900 people, had double that in 1900. Both towns became two important centers of Basque emigration to the New World.

Jean Etchemendy Saragueta, born in 1886 in the House of Ixteotenia in Arnegi, arrived in the United States in September, 1907. He was 21 years old. His final destination was Reno, Nevada, where he met his brothers Michel, who had arrived in 1904, and Joanes, who had arrived only months earlier in March, 1907. His sister Marie would also set sail for the United States years later. His father had died in 1900, leaving behind his pregnant wife and his nine children. For four of them, emigration became their only way out.

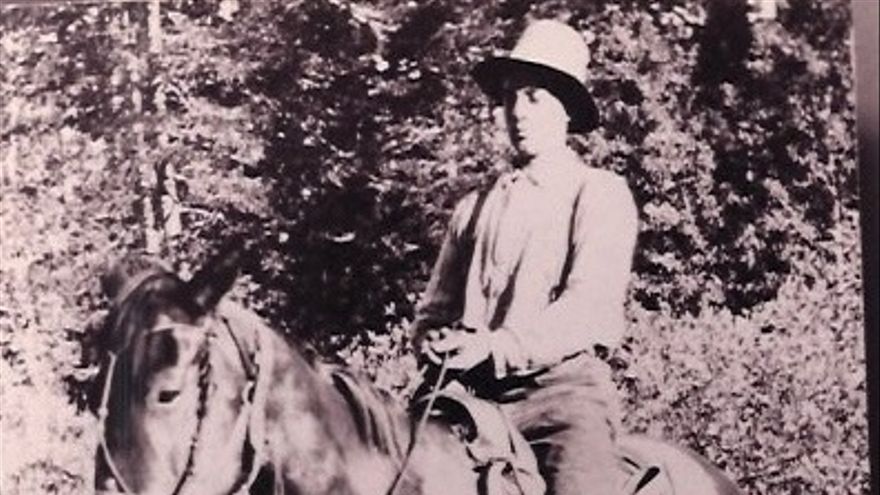

Jean had completed the journey from Arnegi to Reno in 18 days. It would take him 43 years to retrace those same steps. From the time of his arrival until 1912, he did various traveling jobs between Nevada and California. From 1912 to 1917, Jean worked at a wagon loading yard and stagecoach way station in Wellington, Nevada. During his first brief vacation in San Francisco in 1915 he met his future wife Jeanne Trounday Heguy.

Jeanne, born in 1883 in Ortzaize, arrived in New York in 1905 at the age of 22. She was accompanied by her cousin Marie Grace Trounday. Jeanne followed the path taken by her sisters who had emigrated previously, although their destination had been Argentina. She arrived in the small Californian city of Fresno, where she first worked for the Hotel Bascongado, owned, at that time, by the Basque emigrant Jean Bidegaray.

Jean Etchemendy and Jeanne Trounday were married in 1916 in Fresno. In 1917, they moved to Gardnerville, beginning a fruitful career in the hotel business that lasted 55 years. There they ran the East Fork Hotel, between 1917 and 1921, and the Overland Hotel, as owners, from 1921 to 1972. They had six children: John (1917-1995), twins Leon (1918-1988) and Louie (he died at birth, apparently as a result of the so-called Spanish flu), William (1920-2011), Josephine (1923-2006), and Marie (1927-2018). Jean was also involved in sheep farming in the 1920s and was a sheep wool dealer from 1933 until he was almost 100 years old, being the oldest active dealer in the American West.

Just a couple of decades after arriving in the country, Jean and his wife had become respected and successful entrepreneurs, instilling in their children the importance of family, work ethic, and the value of education. In fact, all of them would study at the University of Nevada, Reno.

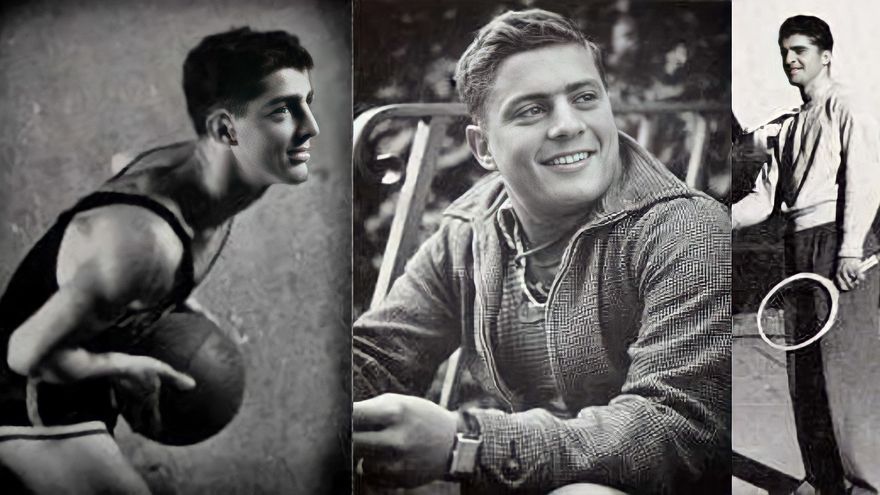

John, Leon, and William all excelled in a variety of sports throughout high school and college, whether it was basketball for John or football for the other two brothers. John had a degree in mining engineering and education, Leon get his in education, and William in Hispanic philology. All three graduated in military science from the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) at the University of Nevada, with a reserve commission as a second lieutenant in the US Army Infantry. As if this weren’t enough, John enrolled in cadet flight school in May 1940 before finishing college, attending among other places the prestigious academy at Randolph Field in San Antonio, Texas, known as the “West Point of the Air.” He graduated in December 1940, receiving the coveted military pilot wings and a second reserve commission as a second lieutenant, this time in the Army Air Corps.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

John Michael Etchemendy Trounday, who had already excelled as a pilot extraordinary, was sent to the Army Air Corps Advanced Flight School as an instructor, serving at air bases in Louisiana and Alabama, where he suffered two plane crashes, though he was unharmed in both. Meanwhile the US entered WWII. Subsequently, John was assigned to the Accelerated Service Test Unit at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, training new pilots first as commander of the 83rd Teaching Squadron and later as group commander until March 1943. In August he was promoted to the rank of major. In January 1944 while he was piloting the P-40 Warhawk fighter plane, he had his last accident, this time at Mitchel Air Force Base in New York. The plane was totally destroyed. After the war ended, in November 1945, John was appointed group commander and flight director at the Central School of Instructors at Randolph Field. In March 1946, John served as deputy director of the Central School of Instructors and as an assistant training and operations officer, flight safety officer, and assistant commander at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. By 1946, John had accumulated more than 2,200 hours of total flight time as a pilot. In June 1946, he was nominated by President Harry S. Truman and consequently named First Lieutenant of the Army, being one of 9,800 chosen from more than 100,000 candidates. Between 1947 and 1949, John assumed command of the 26th Fighter Squadron (one of the first units to fly jet aircraft overseas) of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Group in Okinawa, Japan, with the mission of defending the airspace of the Ryukyu Islands.

After graduating, Leon Etchemendy Trounday was sent directly to the Army base of Fort Ord, in Monterey Bay, California, and from there to the South Pacific, serving in the 7th Infantry Division. He participated in 17 amphibious landings from Attu and Kiska, Alaska, through the Marshall Islands, to the Philippines. On May 11, 1943, they landed at Attu, where the division lost about 600 soldiers. On January 31, 1944, Leon and his comrades-in-arms landed on the islands of Kwajalein Atoll, participating in the capture of Engebi, part of Eniwetok Atoll, on February 18, 1943. Finally, they took part in the invasion of Leyte, where Leon was seriously injured. The Basque-American native of Nevada, Paul Laxalt, of the Army Medical Corps, helped transport him on a stretcher to the hospital, providing care during his recovery. Leon spent the next 14 months in and out of hospitals. He was discharged with honors in January, 1946. He received a Bronze Star, the Purple Heart, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign medal with four battle stars, 17 bronze arrowheads corresponding to as many amphibious landings, the Combat Infantryman Badge, a Presidential Commendation, and two Army Commendations Medals. Leon returned to Nevada where he taught in Reno and Sparks until his mobilization due to the Korean War.

Little brother William Etchemendy Trounday was assigned as Rifle Platoon Leader to L Company, 3rd Brigade, 329th Infantry Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division (the “Thunderbolts”). On June 18, 1944, they landed on Omaha Beach. They fought in Normandy, northern France (capturing the fortress of Saint-Malo, in Brittany), the Ardennes, and in the Rhineland. The division went through France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and Germany. In the Hürtgen Forest, William was wounded in one of the bloodiest battles in US military history with 33,000 casualties, including deaths and injuries. After recovering, he participated in late 1944 in the successful Allied effort that stopped the German counteroffensive in the Battle of the Bulge. In March 1945, the division advanced towards the Rhine river. William was part of the first platoons to reach the river with the aim of crossing the bridge that led to Dusseldorf before it was blown up. However, part of the bridge was dynamited. William fell wounded and was transferred to a hospital in Paris. After a brief convalescence he returned to his unit, which assumed the responsibilities of the occupation and the military government of Austria. He was promoted to captain. For his participation in WWII, he received the Purple Heart with two clusters of oak leaves, a Bronze Star, and four battle stars.

In 1948, the three brothers were able to reunite with the rest of the family in Gardnerville after the end of WWII. In 1949, Jeanne passed away at the age of 66. Accompanied by his little daughter Marie, Jean visited his relatives in Arnegi for the first time. He continued to manage the Overland Hotel until 1953, when he transferred it to another Basque family. In 1958, he married the Nafarroa Beherean Jeanne Lartirigoyen, returning together to the country where they were born. After the death of his second wife, Jean returned to Arnegi for the last time. He passed away in 1990 in Reno at the age of 103 years and seven months. He was the oldest person in Nevada, and was considered one of the most influential people in the history of Douglas County.

After WWII and the Korean War, the brothers remained linked to the armed forces. Leon retired from military service in 1968 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, followed by John in 1971, and William in 1975, both with the rank of Colonel. Between the three they added 84 years of service to their parents’ adopted country, with almost 14 years of combat spanning between the last world war and the Korean War. John, with more than 7,000 flight hours, survived three air accidents and led combat missions in Korea, while Leon fought in WWII where he was seriously wounded, and William fought in both wars, being wounded in battle four times. William is the only one of the brothers who was active during the Vietnam War.

Leon passed away at age 69, John at 78, and William at 90. Both John and William were buried with military honors in Virginia’s Arlington National Cemetery. Marie, the youngest of the family, passed away in 2018, being the last of the first generation of her family born in the United States. Few are the Basque-American families whose children match the spectacular military trajectory of the Etchemendy Trounday. This article serves to honor the memory of all of them.

[1] Reno Gazette-Journal. “Team of Nevada Brothers Compiles Service Records” (February 22, 1952. P. 14).

[2] This article draws on oral history interviews with Jean Etchemendy between 1978 and 1980 by her daughter Josephine and on the stories written by Josephine’s son, Raymond John Uhalde Etchemendy, about his family.

Collaborate with ‘Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945.’

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of two wars” send us an original article on any aspect of WWII or the Civil War and Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Combatientes Vascos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.”