As part of the buildup to the Smithsonian Folklife Festival celebrating the Basque culture, Vince Juaristi is writing a series of articles highlighting the connections between the Basques and Americans. He has graciously allowed me to repost those articles as they appear on Buber’s Basque Page.

Sprawled between the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol, the Smithsonian hosts the National Folklife Festival each year. Hundreds of thousands attend from across America and around the world to study and learn about diverse cultures in the United States. From June 29-July 4 and July 7-10, 2016, this year’s festival will showcase the Basque. In the lead up to this important event, we are publishing a series of historical and human interest articles that demonstrate how Americans and the Basque have crossed paths for centuries. An introductory article ran in January. Additional articles will run monthly through June 2016. We call the series, “Intertwined“.

Sprawled between the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol, the Smithsonian hosts the National Folklife Festival each year. Hundreds of thousands attend from across America and around the world to study and learn about diverse cultures in the United States. From June 29-July 4 and July 7-10, 2016, this year’s festival will showcase the Basque. In the lead up to this important event, we are publishing a series of historical and human interest articles that demonstrate how Americans and the Basque have crossed paths for centuries. An introductory article ran in January. Additional articles will run monthly through June 2016. We call the series, “Intertwined“.

A Basque-American Fairytale

By Vince J. Juaristi

During a bedtime story, a godchild of mine interrupted with a question, “Why are Basque people good?”

How fascinating, I thought. Mother Goose quickly went by the wayside.

“It has to do with a frustrated devil,” I told her. “One day, the devil climbed from the fire and smoke of hell to visit the Basque and turn them bad. With his red forked tongue, he whispered evil temptations in their ears. That’s how the devil works, you see, twisting hope and light into despair and darkness. But no matter how hard he tried, or how much he wagged his devilish tongue, he could not speak Euskera, the Basque language, so he had no power or influence over the Basque people. He finally gave up and returned to hell, and that, my dear godchild, is why the Basque are good to this day.”

The tale satisfied her, and I finished reading the three bears or the three pigs or some other less riveting fairytale for her proper education.

Her question had been a good one, even if it had no objective answer. Years later, I pondered it again, though I asked it differently, “Have the Basque thrived in America?”

The question really had two parts – first, the status of Basque in America, and second, their status compared to others in similar circumstances.

When I turned to the U.S. Census for something quantitative, I didn’t know what I might find. If the data showed the Basque lagging others in America, it would be as disappointing for me as it was for Pinocchio learning that he had descended from a piece of plywood and not the warmth of parents. Worse, it would be a far more difficult story to tell a godchild who already believed in Basque goodness.

But what I discovered confirmed a sentiment that was already tucked away in my heart of hearts.

Basque in Pamplona hold up the Basque flag and raise their red scarves as a sign of cohesion and solidarity, a strong sentiment that the Basque carried with them across the ocean to America where it only grew in strength.

More than 75% of Basque age 25 years or older have some level of college education compared to only 58% of Americans overall. The contrast is starker at higher educational levels where Basque are 50% more likely to hold a graduate or professional degree than other Americans.

This propensity for education makes them 10% more likely to be in the American labor force, and 31% more likely to hold jobs in management, business, science or the arts.

Their median household income is $70,159 compared to the U.S. median of $52,176. Their poverty rate is half the national average, and they are more likely to own their own home. When they do, the home is 48% more valuable than the average American home.

Had I not studied the data myself, I might have been skeptical of such a rosy picture. Indeed, skeptical I should have been. To compare a smaller homogenous group to a larger heterogeneous group risks statistical overreach. Yet to ignore the data would be equally egregious. What the data illuminate are the pointers, like Peter Pan’s northern star, showing areas where Basque excel, and confirming what I and others have witnessed anecdotally for generations.

These pointers – more education, higher wages, and better jobs – are good indicators of a thriving ethnic group. The analysis, consequently, begs a natural question – why have the Basque thrived when others have thrived less or not at all? Are the Basque, indeed, untainted by the devil’s poisonous whispers, or is there another plausible explanation?

Ideally, I’d like to point to a single quality or decision that explains Basque performance, but there isn’t one. Much like Little Red Riding Hood who studied eyes, nose, ears, and teeth to expose the wolf in grandma’s nightie, only a combination of cultural factors can explain the success of the Basque in America. There are no doubt many, but four resonate most – Basque cohesion, a strong work ethic, frugality, and an independent spirit.

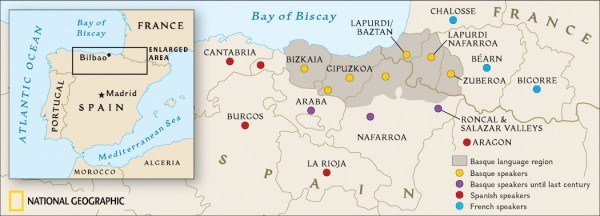

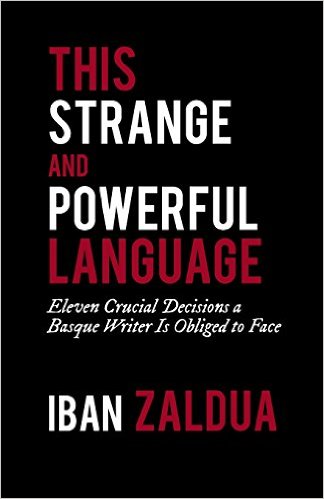

First, the Basque are a cohesive group. They hail from a narrow part of the world, practice Catholicism, revere their own flag, and speak a language that is both ancient and nearly impossible for non-Basque to understand without years of concentrated study. Equally ancient are their special dances, color patterns, costumes, games of strength, and foods that reinforce a bond with each other, their past, and their origins in the Pyrenees.

Basque sheepherders in the United States circa 1970 who toiled daily in the most austere conditions of the American West.

This cohesion does not guarantee Basque success, but it does create a social and economic ecosystem that helps the Basque spin straw into gold. Their bond generates trust, familiarity, cooperation, business associations, and even compeition among members of the group and with others outside the group. The Basque work with and for each other and often look inward for support. If one Basque needs something, another provides it.

The arrangement is common among other ethnic groups that have immigrated to the United States. What makes this tendency so powerful among the Basque is that they started as a cohesive group in Euskadi, their homeland. Amid the isolated peaks of the Pyrenees, they resisted the persistent influences of Spanish and French cultures, laws, and royalty. When they arrived as immigrants in the United States (or elsewhere), their bond only strengthened, which added to their highly productive social and economic relations.

This point recalls the fable of the father who summons his boys to his bedside. He gives them a bundle of sticks and says, “Break these if you can.” Each son strains and strains to do so but fails. Then the father unties the bundle and tells the boys to break each stick and they do so easily. “You see my meaning,” says the father, “there is strength in union.” The Basque know this lesson and stick together.

These shared qualities would advance them little, however, if not for a second characteristic – a driving work ethic.

Measuring work ethic is not easy. Without a record showing the clocked hours of Basque and non-Basque in a day, week, month or year; a productivity curve; or a calculation of watts, it is difficult to quantify or compare the work ethic of groups.

But still valuable evidence abounds. With a relatively small sampling of 57,000 Basque-Americans, anecdotes and personal accounts can offer weighty confirmation of group habits.

During the 1940s and 1950s, the ranchers of the west, for example, petitioned Nevada’s U.S. Senator Patrick McCarran to bring Basque shepherds from Spain for their herding expertise and their remarkable endurance to work from sunup to sundown with little rest and without complaint. At least 1,135 Basque sheepherders came to America and populated the West by this method.

My father and uncle were among them. I’d be negligent if I ignored their work ethic or my mom’s, or the work ethic of so many Basque men and women of their generation whom I watched and admired daily and counted as friends and neighbors for so much of my life. They herded the sheep, tended the bars, made the beds, cooked the meals, and mopped the floors, often seven days a week. A hundred Basque mothers and fathers come to mind still today who have calloused hands, sore backs, and a yearning to get ahead. Their stories cannot be ignored or denied.

As they worked, the Basque earned money, but they were not spendthrifts. On the contrary, their third quality was frugality. When I was a boy, my mother pointed a finger at me and repeated words her mother had taught her. “Spend half,” she said, “and put the other half away.” Her words echo in my head each time I collect a paycheck or balance a budget or launch a foundation, and they always will.

Mom’s advice appears common among the Basque. Annually, the average interest and dividends earned on savings by each American is $1,371. For the Basque, the average is $3,100, over 126% more.

“Oh, ant, why do you work so much?” asked Aesop’s grasshopper. “Come lounge with me.”

“That is not in my nature,” replied the ant. “Better to work and save for the winter.”

“Do what you must,” said the grasshopper.

The Basque are more ant than grasshopper. They work and save; it is simply in their nature.

Tied like a bow around this cultural cohesion, work ethic, and frugality is a fourth characteristic which John Adams, an American founding father, called a “High and independent spirit.” It might be the most important of all Basque qualities.

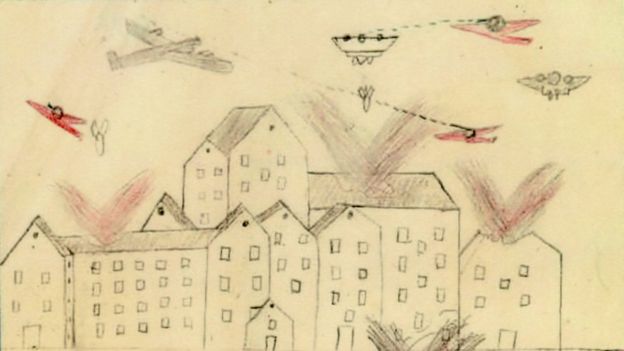

This spirit nests in the heart of every Basque and dates to ancient times. When the Romans invaded, the Basque resisted; when Isabel asked for allegiance, the Basque exacted a price; when a king imposed a tax, the Basque refused to pay and formed a militia; when Franco outlawed Euskera, the Basque defied the order. Despite these confrontations – and perhaps because of them – the Basque persevered, but not without pain or death. Their sacrifices only enriched their pride in language, culture, and an ancient heritage. Loss made what they had more precious.

They brought this independent spirit across the ocean where it blossomed in America’s free soil, a land that Goldilocks herself might have said was “just right.” The Basque shepherds who lived in the hills, fought coyotes and mountain lions, slept under stars, and ate by campfires each epitomized, in their own way, the self reliance that Emerson had spoken of a century earlier. They looked not to old Europe or government to shape their collective future, but to themselves and to each other.

Not surprisingly, this streak of independence makes the Basque 34% more likely than other Americans to earn their daily bread as self-employed entrepreneurs rather than salaried employees working for someone else. In my own family, mom and dad owned and operated two businesses, and two of their children are now CEOs of companies.

When my godchild, who is Danish and raised on a healthy diet of Hans Christian Andersen, asks again about the Basque, I can surely repeat the story of the frustrated devil, but I’ll have another story for her that reads very much like a fairytale. Numbers have confirmed what my heart and experience already knew. I’ll tell her of a people who came with nothing, worked until fingers bled, saved and stuck together, and stood independent and strong on two firmly committed legs. It’s a good story and almost complete except for one ingredient – the ending.

It’s too soon to say that all lived happily ever after. The Basque are still in the throes of the tale, still seeking their fortunes, and occasionally, still fighting big bad wolves. Yet all signs so far point to these Basque-American ducklings slowly emerging as swans.

Share this / Partekatu hau:

Like this:

Like Loading...

Please help. I am trying to assemble Basque recipes for a cookbook. All recipes submitted to me will be credited to the donor. Send any to bacalaoconspiracy@gmail.com and visit my websites at http://chefjohnmaxwell.com/ or http://bacalaoconspiracy.com/ When the cookbook is published every one who’s recipe is included will get a signed copy from me at no charge.

Please help. I am trying to assemble Basque recipes for a cookbook. All recipes submitted to me will be credited to the donor. Send any to bacalaoconspiracy@gmail.com and visit my websites at http://chefjohnmaxwell.com/ or http://bacalaoconspiracy.com/ When the cookbook is published every one who’s recipe is included will get a signed copy from me at no charge.

One minor spoiler: there are some elements of the supernatural in the story. I’m not yet sure how I feel about them. I won’t say much more, and I’ll reserve judgement until I see how they play out in the next two novels that continue Amaia’s adventures in the Basque Country.

One minor spoiler: there are some elements of the supernatural in the story. I’m not yet sure how I feel about them. I won’t say much more, and I’ll reserve judgement until I see how they play out in the next two novels that continue Amaia’s adventures in the Basque Country.

Sprawled between the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol, the Smithsonian hosts the National Folklife Festival each year. Hundreds of thousands attend from across America and around the world to study and learn about diverse cultures in the United States. From June 29-July 4 and July 7-10, 2016, this year’s festival will showcase the Basque. In the lead up to this important event, we are publishing a series of historical and human interest articles that demonstrate how Americans and the Basque have crossed paths for centuries. An introductory article ran in January. Additional articles will run monthly through June 2016. We call the series, “Intertwined“.

Sprawled between the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol, the Smithsonian hosts the National Folklife Festival each year. Hundreds of thousands attend from across America and around the world to study and learn about diverse cultures in the United States. From June 29-July 4 and July 7-10, 2016, this year’s festival will showcase the Basque. In the lead up to this important event, we are publishing a series of historical and human interest articles that demonstrate how Americans and the Basque have crossed paths for centuries. An introductory article ran in January. Additional articles will run monthly through June 2016. We call the series, “Intertwined“.