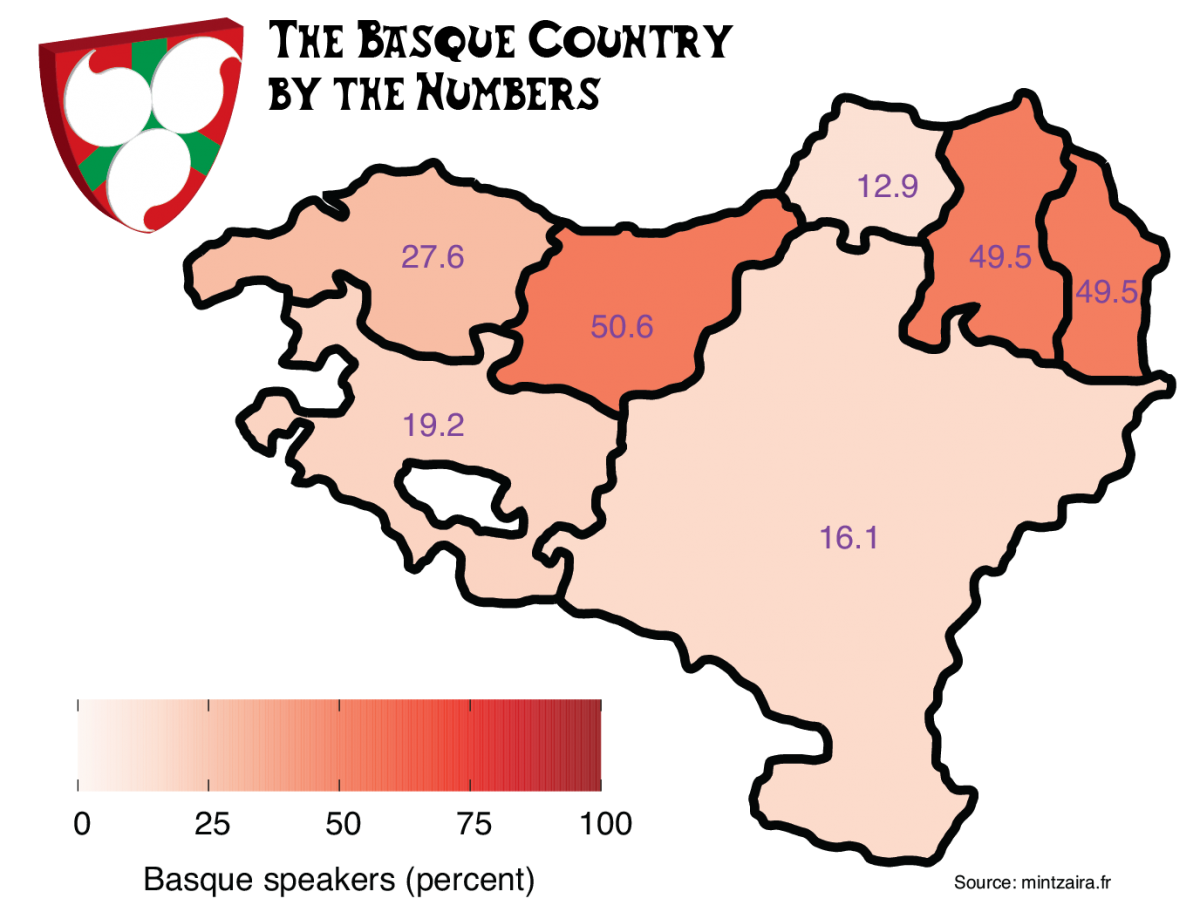

The percent of people who can speak Euskara. The numbers for Zuberoa and Nafarroa Beherea are shared. Source: https://www.mintzaira.fr/fileadmin/documents/Aktualitateak/015_VI_ENQUETE_PB__Fr.pdf

The percent of people who can speak Euskara. The numbers for Zuberoa and Nafarroa Beherea are shared. Source: https://www.mintzaira.fr/fileadmin/documents/Aktualitateak/015_VI_ENQUETE_PB__Fr.pdf

My friend Benoit Etcheverry Macazaga posted on his Facebook page a link to Mintza Lasai, a citizen effort that started in November 2011 with the goal of revitalizing Basque in BAB: Bayonne-Anglet-Biarritz. In particular, they have a few resources on Euskara including a practical dictionary in Euskara, French, Spanish, and English as well as a chart of some important words and concepts. These are only a few of the items they have. They also have guides for specific topics, including family, food, school, and music. The best thing? They are all free to download as PDFs that you can then print! These are mostly aimed at French speakers, but they may still prove valuable to others who are trying to learn a bit more Euskara.

If you know of other similar resources, please share!

It was late when Maite finally boarded the train from Bilbao to Gernika. Her research project was starting to take more and more time, time that she couldn’t then spend with her ailing parents. Every extra hour she spent in the lab led to a ton of extra guilt she carried on her shoulders. During moments like these, she was almost certain that she would turn down the offer to go to the United States.

At the same time, her project was actually getting exciting. It had taken her a long time to master the basics, particularly since she couldn’t stay as long as some of the other students who lived closer. And there was the constant frustration of trying something that didn’t work or making seemingly stupid mistakes that caused her to have to start some task over. Her advisor was patient with her, and had never berated her for her slow progress (unlike some of the other professors she had heard about) but she couldn’t help feeling that she was constantly letting her advisor down. She sighed. She felt like she was letting pretty much everyone in her life down.

Buber’s Basque Story is a weekly serial. While it is a work of fiction, it has elements from both my own experiences and stories I’ve heard from various people. The characters, while in some cases inspired by real people, aren’t directly modeled on anyone in particular. I expect there will be inconsistencies and factual errors. I don’t know where it is going, and I’ll probably forget where it’s been. Why am I doing this? To give me an excuse and a deadline for some creative writing and because I thought people might enjoy it. Gozatu!

Her thoughts drifted to Kepa and she let a small smile cross her lips. She had known Kepa for so long and, ever since they were teenagers, there had been some amount of mutual attraction, but the poor boy had never acted on it, had never even expressed any interest in her beyond a platonic friendship. She wondered if he even admitted to himself that he was interested in her. “At least,” she thought to herself, “I made my feelings clear.”

The train rumbled down the ancient track, taking so much longer than it had any reason to. She often thought about driving to school, but then parking was always such a pain in Bilbao. Anyways, there was always more work to do, and she pulled a couple of papers out of her backpack to read for the duration.

She shoved the papers back in her backpack as the train ambled up to the train station. She departed and started walking home. Her path took her down by the market and the bars were still open. Crowds of people were sitting in the open-air patios, cañas and glasses of kalimotxo in hand. She saw a group she remembered from her one year in high school in Gernika, but they didn’t seem to see her so she kept walking. While some part of her yearned to bump into a friend and have a drink, she also knew she needed to get to bed as she had an early start in the morning. Her advisor had asked for a report on her progress that she hadn’t even started yet.

She got to the apartment building that housed the apartment she shared with her parents. Letting herself in, she climbed the dark stairs and quietly opened the door to apartment 3D. As she expected, her parents were already in bed. She tiptoed to the kitchen to make herself a snack before bed. On the table, she found a freshly made tortilla — with chorizo, her favorite! — a bottle of wine, and a small glass. She smiled as she sat down to eat.

This article originally appeared in Spanish at El Diario.

At 36 years old, the Zuberoan Jean Pierre Laxalt Etchart found himself in Ardentes, in central France — about 650 kilometers from his hometown of Aloze — immersed in the Great War of 1914 that would devastate part of the country. The difference from his peers regarding his participation in the conflict was that Jean Pierre was recruited by the United States Army, a country in which he had lived since 1902. He returned to defend France in March 1918, for the first time (and last) time since his departure, 16 years earlier. He was one of the “Fighting Foresters” of the Engineer Regiment — the largest regiment that ever existed in the US Army. During the same period of time, in one of those fearsome trench on the fronts, was the French Army soldier Jean Michel (Alpetche) Bassus, born in 1894 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, of parents from Nafarroa Beherea, and whose life would intertwine unpredictably with those of the Laxalts in the not too distant future.

“Echoes of two wars, 1936-1945” aims to disseminate the stories of those Basques and Navarrese who participated in two of the warfare events that defined the future of much of the 20th century. With this blog, the intention of the Sancho de Beurko Association is to rescue from anonymity the thousands of people who constitute the backbone of the historical memory of the Basque and Navarre communities, on both sides of the Pyrenees, and their diasporas of emigrants and descendants, with a primary emphasis on the United States, during the period from 1936 to 1945.

THE AUTHORS

Guillermo Tabernilla is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association, a non-profit organization that studies the history of the Basques and Navarrese from both sides of the Pyrenees in the Spanish Civil War and in World War II. He is currently their secretary and community manager. He is also editor of the digital magazine Saibigain. Between 2008 and 2016 he directed the catalog of the “Iron Belt” for the Heritage Directorate of the Basque Government and is, together with Pedro J. Oiarzabal, principal investigator of the Fighting Basques Project, a memory project on the Basques and Navarrese in the Second World War in collaboration with the federation of Basque Organizations of North America.

Pedro J. Oiarzabal is a Doctor in Political Science-Basque Studies, granted by the University of Nevada, Reno (USA). For two decades, his work has focused on research and consulting on public policies (citizenship abroad and return), diasporas and new technologies, and social and historical memory (oral history, migration and exile), with special emphasis on the Basque case. He is the author of more than twenty publications. He has authored the blog “Basque Identity 2.0” by EITB and “Diaspora Bizia” by EuskalKultura.eus. On Twitter @Oiarzabal.

Josu M. Aguirregabiria is a researcher and founder of the Sancho de Beurko Association and is currently its president. A specialist in the Civil War in Álava, he is the author of several publications related to this topic, among which “La batalla de Villarreal de Álava” (2015) y “Seis días de guerra en el frente de Álava. Comienza la ofensiva de Mola” (2018) stand out.

After his demobilization, Jean Pierre resumed his life as a sheep herder in Nevada. His brothers, Pierre and Dominique Laxalt Etchart, who came to the United States in 1904 and 1906, respectively, had previously and successfully accompanied him in his work for a few years starting in 1910. Both had been born in Liginaga; Pierre, in 1878, and Dominique in 1886. In 1914, Pierre “Pete” Laxalt Etchart married Marie “Mary” Ucarriet, born in 1892 in Aldude, Nafarroa Beherea, and arrived in the United States with her parents in 1912. They had four children: Gabriel “Gabe” Peter (1915-1979), Adelle Marie (1917-2003), Robert John (1920-1972) and Lucille Catherine (1921-1980). Three of them, Gabriel, Robert and Lucille took an active part in World War II (WWII).

Gabriel and Robert enlisted in the Air Force in 1941. Gabriel Laxalt Ucarriet did so eight months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, while Robert Laxalt Ucarriet volunteered two days after the Japanese attack. Gabriel was assigned to the maintenance personnel of the air fleet, and served at the end of the war in the 534th Air Service Group, being licensed with the rank of sergeant in 1945. Robert was assigned to the Icelandic Base Command, established by the US Army on July 7, 1941 for the defense of the island and as a strategic point between Europe and North America. There he remained throughout the conflict.

In August 1941, Lucille Laxalt Ucarriet enrolled at the Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, California, to train as a nurse. While in nursing school, Lucille was admitted to the US Cadet Nurse Corps on July 1, 1943, the date of its creation by the US Congress. They aimed to train nurses for the armed forces and government and civilian hospitals. More than 124,000 nurses who enrolled in this federal program graduated during the course of the war to fill the severe shortage of nurses, both at home and abroad. The government again required the active participation of women, but not on the same terms of equality as men. As of today, the women of the Cadet Nurse Corps are the only ones of all the uniformed service men and women that served in WWII that have yet to be recognized as war veterans by the US government.

In December 1920, a young woman of 29 years old from Nafarroa Beherea, Therèse Alpetche Bassus, arrived at the Port of New York from Bordeaux, France, where her family managed the Hotel Amerika and one of the first travel agencies between Europe and the Americas. Therèse “Theresa,” born in 1891 in Baigorri, Nafarroa Beherea, was destined for San Francisco. It was in this city, at the Hotel España, owned by a Basque family, where her brother Jean Michel resided, who, after the end of the Great War, had arrived in October 1919, following in the footsteps of his brother Maurice, a resident of USA since 1914. Jean Michel was dying from the effects of a poison gas attack used during the war. Therèse’s goal was to return to France with her brother. Unfortunately, Jean Michel died in 1921 and was buried in Reno, Nevada, where his sister erected a monolith in his memory. Therèse decided to stay in the country, marrying Dominique Laxalt Etchart shortly after. They had six children: Paul Dominique (1922-2018), Robert Peter “Bob” (1923-2001), Suzanne Marie (Sister Mary Robert of the Order of the Holy Family; 1925-2019), John Maurice (1926-2011), Marie Aurelie (1928-2019) and Peter Dominique “Mick” (1931-2010).

Like their cousins, three of the Laxalt-Alpetche brothers also contributed to the war effort. Paul Dominique Laxalt Alpetche was drafted in 1942 and, for three long years — 18 months these abroad — he served in the Army Medical Corps (a non-combatant unit), until his discharge with the rank of sergeant. It was during the Battle of Leyte, in the Philippines, where he took care of a young Basque-Nevadan officer, Leon Etchemendy Trounday (a hero of the Aleutians), who was seriously wounded. “Too much blood, too many wounded, and soldiers dying,” Paul would write, decades later, in his memoirs (1). Paul was later elected Lieutenant Governor of Nevada (1962-1964), Governor of Nevada (1967-1971), and finally US Senator for the State of Nevada (1974-1987). Paul became the first Basque senator in American history. He was the right hand and close friend of President Ronald Reagan. Paul was buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia.

His brother Robert Laxalt Alpetche interrupted his studies to enlist in the army. However, he was not accepted due to a slight heart murmur. Through family political connections, Robert finally landed a job with the State Department Diplomatic Service in Washington DC. He was assigned as a code officer to the Diplomatic Legation and sent to the Belgian Congo in 1944. He served in a jungle outpost in the context of a secret spy war between the Allies (the Office of Strategic Services, the current CIA) and the Germans for control of a mine in Katanga province that produced a little-known (at the time) mineral called uranium — the essential ingredient of the atomic bomb (2). Robert fell ill with malaria and was sent home in March 1945. He was 21 years old. In 1951, Robert accompanied his father to his birthplace for the first time after 47 years as a sheep herder in Nevada and Northern California. Based on his father’s story, he wrote Sweet Promised Land (1957), his second novel, and one of his best-known books. Robert founded the University of Nevada Press in 1961 and was its director until 1983. Together with William A. Douglass and Jon Bilbao they founded the Basque Studies Program at the University of Nevada in 1967. Robert was a prolific writer of fiction and nonfiction. He became the “voice of the Basques” in the American West (3).

Near the end of the war, John Maurice Laxalt Alpetche was drafted by the Navy, serving on board the munitions ship USS Mount Katmai in the Western Pacific. He graduated with a second-class administrative degree in July 1946. He left his law firm to participate in his brother Paul’s election campaigns, later settling in Washington DC.

Paul’s death in 2018 at the age of 96, and that of Suzanne Marie (Sister Mary Robert), in October of the next year at the age of 94, marked the end of the first Basque generation of the Laxalts born in the USA. The Laxalt-Ucarriets, although they died relatively young, left behind a legacy of overcoming and defending freedoms that today we try to preserve at all costs. The Laxalt-Alpetches, perhaps the most visible face of this extraordinary Basque-American family, are possibly the paradigm of a history of successful emigration, of struggle for survival, and of the social, economic and political conquest of a family in one generation. They made the American Wild West, and especially Nevada, their home, a value that the Laxalts continue to treasure to this day with great zeal.

If you want to collaborate with “Echoes of Two Wars,” send us an original article on any aspect of the WWII or the Spanish Civil War and the Basque or Navarre participation to the following email: sanchobeurko@gmail.com

Articles selected for publication will receive a signed copy of “Basque Combatants in World War II”.

(1) Laxalt, Paul. (2000). Nevada’s Paul Laxalt. To Memoir. Reno, Nevada: Jack Bacon & Co.

(2) Robert Laxalt wrote in 1998 about his adventures in the Belgian Congo during the WWII, under the title, A Private War: An American Code Officer in the Belgian Congo. (Reno: University of Nevada Press).

(3) Rio, David. (2007). Robert Laxalt: The voice of the Basques in American literature. Reno: Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, Reno.

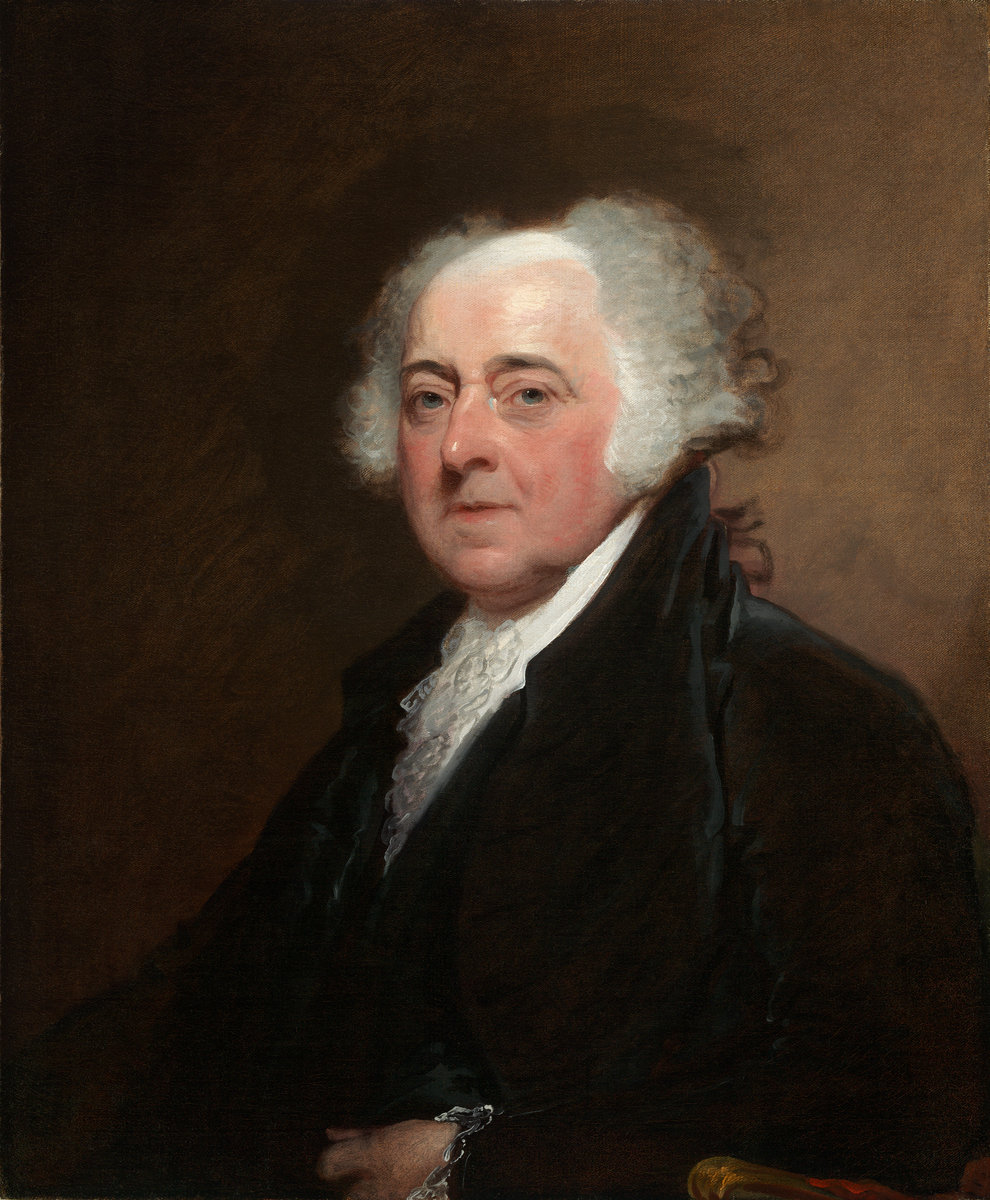

It was 1779 and John Adams and his sons were on their way to Paris with the goal of establishing a commercial treaty with Great Britain and ending the Revolutionary War. On the way, however, their ship was battered by storms and they limped their way into Spain. After some debate and discussion, Adams and his retinue decided to take the land route to Paris, which took them through Bilbao and the heart of the Basque Country. What he learned about the Basque people and their government found its way into his A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. In turn, Bilbao has commemorated his visit with a bust in the city.

Primary source: The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Vol IV by Charles Francis Adams.

A few days later, Maite found herself sitting in her thermodynamics class. She hated the idea of taking summer classes. Since moving to Gernika with her parents, she had already missed out on so many things with her friends, and commuting to Bilbao to take classes certainly didn’t help her social life, but she wanted to finish her degree as fast as possible. She already felt guilty about continuing with school instead of finding a “real” job to help support her parents; she didn’t want to drag it out longer than necessary.

Buber’s Basque Story is a weekly serial. While it is a work of fiction, it has elements from both my own experiences and stories I’ve heard from various people. The characters, while in some cases inspired by real people, aren’t directly modeled on anyone in particular. I expect there will be inconsistencies and factual errors. I don’t know where it is going, and I’ll probably forget where it’s been. Why am I doing this? To give me an excuse and a deadline for some creative writing and because I thought people might enjoy it. Gozatu!

Her parents had run the local Herriko Taberna for as long as she could remember and had almost literally worked themselves to death. Her ama would wake up at some ungodly hour to clean the bar and restaurant and begin cooking the day’s meals. Maite could remember the smells of the warm bread and the hot coffee as she got up, usually several hours after her ama. Once in a while, the less pleasant smells of cooking octopus made it to her pillow in the apartment adjacent the restaurant, which usually caused her to bury her head under the blankets.

Her aita also typically slept in, but only because he had been up so late the night before, serving drinks until the last of the bar’s patrons left in the wee hours of the night. She always had fallen asleep to the sounds of pilota blaring from the bar’s television, the patrons — including her aita — yelling as their favored player missed a point or cheering as the match ended with their man winning. Once a week, it was her aita’s job to head to Gernika to buy supplies for the restaurant and, during the summers when there was no school, Maite would join him. She had always been in awe of how everyone knew her aita and how he seemed to know everyone. As they walked the streets going from one shop to another, it seemed like hundreds of people would yell out a “kaixo!” or “eup!” She always thought that her aita must have been the most important man in the world. Or at least the Basque Country.

However, the restaurant business slowly took its toll on their health, and her parents had to retire. Seeing as how the medical services where they lived weren’t great, they decided to move to Gernika. They had saved enough over the many years of running the Herriko Taberna that they could afford an apartment not far from the plaza. Her parents would often wander down to the plaza where they could bump into all of her aita’s old acquaintances.

Maite was seventeen when they moved, nearing the end of high school, and it was a hard transition for her. She had to leave her cuadrilla, the friends she had known since childhood, behind, and there wasn’t time to make new friends as she figured out her plans for the uni. Once she started her university studies, there was even less time for her old friends. She tried to make it back as often as she could, to see the old cuadrilla and do a night or two of gau pasa, but it was becoming more and more difficult. As she neared her university graduation, while excited by the prospects for her career, she lamented the longer distance that had grown between her and her friends. She feared the same might happen with her parents, especially if she decided to accept the offer to go to graduate school in the United States.

I’ve delved into my genealogy a bit, scouring the priests’ books that document births, deaths, and marriages in each little town. Going back centuries, the names are all too familiar: Pedro, Jose, Domingo, Juan for the men; Josefa, Maria, Manuela, Magdalena for the women. Once in a while, there will be a Bartolome, or an Agustina, but what they all have in common is their Spanish origin. However, if you go to the Basque Country today, you’ll find a much wider variety of names with a much more exotic sound, names like Aritz, Endika, Iratxe, Eneritz, Egoitz. The history of simply naming people in Basque has a long and complicated history.

This Basque Fact of the Week inspired by a question from Ray Baehr. Thanks Ray!

Primary sources: Auñamendi Entziklopedia. Nombre. Available at: http://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/nombre/ar-98475/; Auñamendi Entziklopedia. Antroponimia. Available at: http://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/es/antroponimia/ar-1301/

My dad was from Munitibar-Arbatzegi-Gerrikaitz. My friend — and distant cousin — Jon Zuazo sent me this video, made by Karmelo Goikoetxea. It is simply spectacular. It must have been hard for the men and women who, like my dad, had to leave this behind…

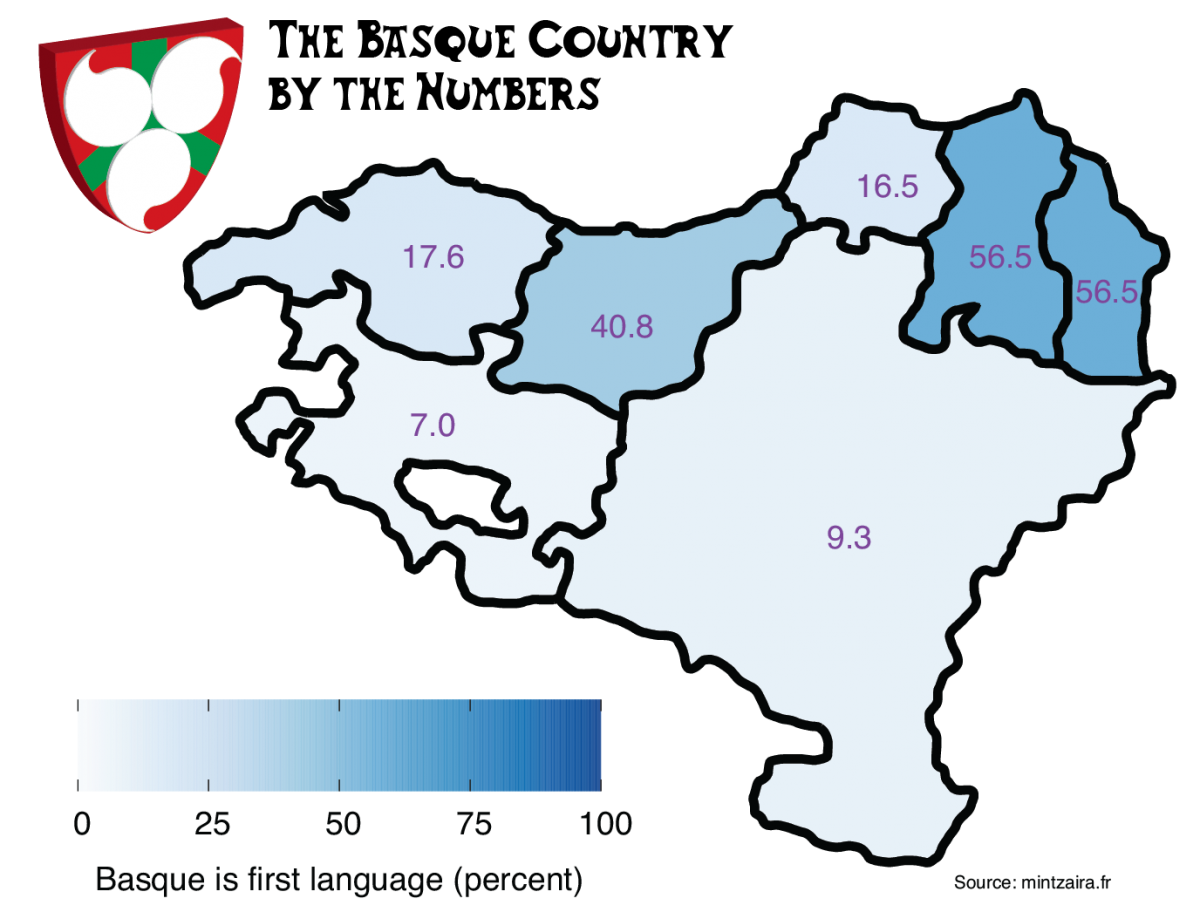

The percent of people who have Euskara as their first language. The numbers for Zuberoa and Nafarroa Beherea are shared. Source: https://www.mintzaira.fr/fileadmin/documents/Aktualitateak/015_VI_ENQUETE_PB__Fr.pdf

It was about nine thirty in the morning when Maite’s little Fiat pulled up again outside of Goikoetxebarri, the baserri where Kepa lived with his mom.

“Mil esker for the ride,” said Kepa over a repressed yawn as he opened the door. “Are you sure you don’t want to crash here for a while, before driving home? If you are as tired as I am…”

“And sleep in that creepy room with those pictures of your uncle?” Maite replied, shaking her head. “No thanks.”

Buber’s Basque Story is a weekly serial. While it is a work of fiction, it has elements from both my own experiences and stories I’ve heard from various people. The characters, while in some cases inspired by real people, aren’t directly modeled on anyone in particular. I expect there will be inconsistencies and factual errors. I don’t know where it is going, and I’ll probably forget where it’s been. Why am I doing this? To give me an excuse and a deadline for some creative writing and because I thought people might enjoy it. Gozatu!

Kepa did have to admit that the middle room was a little creepy. His ama insisted that they keep the photos of his aita’s uncle, Domingo, up on the wall. Domingo had died fighting for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War as Franco’s forces had sieged Bilbao, and the family had always honored his sacrifice by having many photos of the then-young man around the house. They had all gotten consolidated in the middle bedroom upstairs and now the shrine to his great uncle gave the room a very disturbing atmosphere.

“Fair enough,” Kepa said. “But, at least come in for a coffee. I’m sure ama saw us drive up and already has a glass ready for you.”

Maite smiled in defeat. “Ados,” she said as she turned off the engine and got out of the car.

The smell of coffee filled their senses as they passed the foyer into the small kitchen.

“Egun on!” said Kepa’s ama as the two entered the kitchen. She placed two glasses of coffee on the small table, beckoning them to sit. The table was already filled with cookies and biscuits.

“How are the fish, Mari Carmen?” asked Maite as she took a seat at the table.

Ever since they were children, Maite had always asked Kepa’s ama, Mari Carmen, about her fish. She and her parents had come to dinner at the baserri one night and Mari Carmen had served the best fish Maite had ever tasted. She had assumed that Mari Carmen must have a personal pond full of the best and freshest fish in the Basque Country and ever since she had asked Mari Carmen about her wonderful fish. Even when she grew older, she kept the conceit going as an inside joke.

Mari Carmen smiled. “The fish are wonderful, as always. How was the fiesta?”

“It was great,” said Kepa as he shoved a few of the cookies into his mouth and took a sip of his coffee. “Koldo’s new band is really good. They have some excellent songs and all of them are great musicians. I think they could do really well.”

Maite nodded enthusiastically. “I agree. They’re better than all of the other new bands I’ve heard and better than most of the ones that are on the radio. They are really talented.”

“Pozik nago,” replied Mari Carmen. “I’m glad Koldo has finally found his place.”

Kepa knew what she meant. Koldo had struggled to really find his footing as an adult. He had tried various jobs, working at one of the factories, taking classes to be a mechanic, tending bar, but nothing had stuck. He seemed to only be happy when making music.

Maite finished her coffee and stood up. “Well, I better go. Thanks for the coffee Mari Carmen.”

“Ez horregatik, neska. Ondo ibili,” replied Mari Carmen.

Kepa walked Maite out to her car. “Thanks again for the ride. I really appreciate it. And sorry for being so grumpy at the beginning.”

Maite laughed. “If you weren’t grumpy, you wouldn’t be Kepa.”

Kepa leaned in to give Maite a kiss on each cheek, but Maite grabbed his head and planted a kiss on his lips. “Ikusi arte,” she said with a devious smile.

Kepa just stood there, befuddled, as Maite drove off.