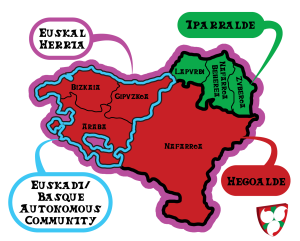

The Olympics are nearly over. As I posted a few weeks ago, the Basque Country – including Euskadi, Iparralde, and Nafarroa – sent 43 athletes to the Olympic Games in Paris. How did they do? Some of the “big” names, like Chourraut and Rahm, didn’t do as well as hoped. However, including individual medals given to players in team sports, this Basque contingent won 8 medals! If we count team wins as only one medal (and to be fair, those would be “shared” with the rest of the teams they played with which included non-Basque athletes), the Basques won 1 individual medal and another 4 team medals. To put that in perspective, that as many as countries like Austria, Czechia, and Mexico won. In any case, all of these athletes gave their all and deserve a round of applause!

Here is a list of all Basque athletes and their achievements at the Paris Olympics.

- Gracia Alonso (3×3 basketball)

- The team won silver (Alonso played for Spain)

- Alex Aranburu (road cycling)

- Finished 18th in the Men’s Road Race

- José ‘Chefo’ Basterra (field hockey)

- The team finished 4th (Basterra played for Spain)

- Esther Briz (rowing)

- Finished 7th in Women’s Pair

- Dario Brizuela (basketball)

- The team finished 10th (Brizuela played for Spain)

- John Cabang (track and field-hurdles)

- Did not start in the Repechage – Heat 2

- Maialen Chourraut (whitewater canoeing)

- Finished 12th in the Women’s Kayak Single

- Finished 12th in the Women’s Kayak Cross

- Carlota Ciganda (golf)

- Finished 49th

- Andy Criere (surfing)

- Finished 17th

- Virginia Diaz (rowing)

- Finished 12th in Women’s Single Sculls

- Joan Duru (surfing)

- Finished 5th

- Tessy Ebosele (track and field-long jump)

- Finished 16th in Qualification – Group A

- Pau Echaniz (whitewater canoeing)

- Won bronze in the Men’s Kayak Single

- Nadia Erostarbe (surfing)

- Finished 5th

- Maitane Etxeberria (handball)

- The team finished 12th (Etxebarria played for Spain)

- Lucía García (soccer)

- The team finished 4th (García played for Spain)

- Imanol Garciandia (handball)

- The team won bronze (Garciandia played for Spain)

- Janire Gonzalez-Etxabarri (surfing)

- Finished 17th

- Oihane Hernández (soccer)

- The team finished 4th (Hernádez played for Spain)

- Sergey Hernandez (reserve) (handball)

- The team won bronze (Hernandez played for Spain, though as a reserve he wasn’t part of the winning team)

- Oier Ibarretxe (boxing)

- Finished 17th

- Alain Kortabitarte (skateboarding)

- Finished 19th

- Naia Laso (skateboarding)

- Finished 7th

- Begoña Lazcano (flatwater canoeing)

- Finished 25th in the Women’s Kayak Single 500m

- Miren Lazkano (slalom canoeing)

- Finished 10th in Women’s Canoe Single

- Finished 17th in Women’s Kayak Cross

- Oier Lazkano (road cycling)

- Finished 35th in the Men’s Road Race

- Finished 26th in the Men’s Individual Time Trial

- Elene Lete (reserve) (soccer)

- Didn’t seem to attend the Games

- Hortense Limouzin (3×3 basketball)

- The team finished 8th (Limouzin played for France)

- Xabier Lopez de Arostegi (basketball)

- The team finished 10th (Lopez de Arostegi played for Spain)

- Majida Maayouf (track and field-marathon)

- Finished 17th

- Asier Martinez (track and field-hurdles)

- Finished 5th in Semi-Final 3 of the Men’s 110m Hurdles

- Alberto Munarriz (water polo)

- The team finished 6th (Munarriz played for Spain)

- Kauldi Odriozola (handball)

- The team won bronze (Ordiozola played for Spain)

- Aimar Oroz (soccer)

- The team won gold (Oroz played for Spain)

- Jon Pacheco (soccer)

- The team won gold (Pacheco played for Spain)

- Irene Paredes (soccer)

- The team finished 4th (Paredes played for Spain)

- Jon Rahm (golf)

- Finished 5th

- Bibiane Schulze (soccer)

- The team won bronze (Schulze played for Germany)

- Salma Solaun (gymnastics)

- Finished 10th in the Group All-Around

- Lysa Tchaptchet (handball)

- The team finished 12th (Tchaptchet played for Spain)

- Ariane Toro (judo)

- Finished 17th in the Women 52 kg

- Finished 9th in the Mixed Team

- Beñat Turrientes (soccer)

- The team won gold (Turrientes played for Spain)

- Rafa Vilallonga (field hockey)

- The team finished 4th (Vilallonga played for Spain)

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Official Site of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games; Comienzan los Juegos de París 2024 con 43 deportistas vascos y vascas, EITB.eus; 43 vascos en los Juegos Olímpicos de París, Deia.com