I’ve often heard that the Basques have never been conquered. However, during the Muslim invasion of what would eventually become Spain, they reached the borders of the Basque region. This led to significant military, political, and even familial interactions between the Muslims and the Basques. In fact, one of the most prominent families of the time, the Iñigo family that effectively founded the Kingdom of Pamplona, were closely related to their neighbors, the Muslim Banu Qasi family.

- The Banu Qasi dynasty is said to have started with the Christian Count Casio, or Cassius, shortly after the arrival of Muslim troops to the Ebro valley in 712 or 713. We know little about Casio himself. He was possibly from the southern Nafarroan town of Tudela. After converting to Islam, he supposedly traveled to Damascus to pledge his loyalty to Al-Walid, the Caliph of the Umayyad.

- His descendants became known as the Banu Qasi, an important dynasty of rulers in the Ebro valley region. Their territory bordered what would become the Kingdom of Pamplona/Nafarroa to the south.

- The Banu Qasi family was intertwined with the Iñigo family who were prominent in the Kingdom of Pamplona. Because of their close connections, a member of the Banu Qasi family, Mutarrif ibn Musa ibn Fortun, was appointed governor of Pamplona in 798 (and murdered the following year). Similarly, Onneca, the mother of the first King of Pamplona Eneko (Iñigo) Arista, after the death of Iñigo’s father, married Musa ibn Fortun. Their son, Musa ibn Musa, became an important leader of the Banu Qasi dynasty. Musa, in turn, married one of Arista’s daughters, becoming both his half-brother and son-in-law.

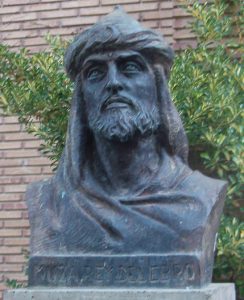

- Under Musa ibn Musa, the family gained new prominence. He allied with his brother-in-law, García Iñiguez, son of Eneko Arista, to ambush and capture the Wali of Zaragoza, Harit. This in turn led Emir Abd al-Rahman II to attack Pamplona. This cycle of antagonism between ibn Musa and the Emir would continue, with ibn Musa on the losing side and the Emir making greater inroads to Pamplona. Despite this, his power and relationship with the Emir grew and he became ruler of the region. His power and influence were so great that he was sometimes called the third king of Hispania (maybe at his own order).

- Under Musa ibn Musa, his troops participated with the Basques in the second Battle of Roncevaux (Orreaga) Pass in 824, in which they defeated the advancing Carolingians. This victory led directly to the establishment of the Kingdom of Pamplona.

- After the death of Eneko Arista in 851, Pamplona aligned itself more with Asturias and less with the Banu Qasi. This rift led ibn Musa, at the behest of the Emir, to plunder Araba, in retaliation for the Basques having helped the Asturians against their interests. ibn Musa’s time ended when he was killed fighting his son-in-law.

- After his death, ibn Musa’s sons led uprisings in the area, taking several prominent towns in 872. However, their victories were short-lived and by 875 all but one was dead. Because King García Íñiguez of Pamplona and other Basque families had supported these uprisings, the Emir initiated new campaigns against them.

- ibn Musa’s grandson, Muhammad ibn Lubb, solidified his control of the family by 885. However, the weakening of the emirate in Cordoba meant that there was less central oversight of his rule. He caused significant conflict in the region until his death by treachery in 898. His son Lubb ibn Muhammad continued hostilities until the Jimena family took over the Kingdom of Pamplona from the Iñigo family. In 907, Lubb ibn Muhammad is killed and the decline of the Banu Qasi dynasty begins.

Primary sources: Etxegarai Garaikoetxea, Mikel. Banu Qasi. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2024. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/banu-qasi/ar-10935/; Banu Qasi, Wikipedia