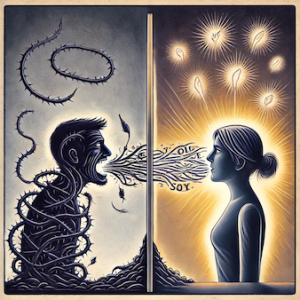

Agindua zorra, esan ohi da.

A promise is a debt, it’s always been said.

.

These proverbs were collected by Jon Aske. For the full list, along with the origin and interpretation of each proverb, click this link.

Agindua zorra, esan ohi da.

A promise is a debt, it’s always been said.

.

Music and singing is such an important part of Basque culture. No Basque festival or party is complete without an accordion or a txistu. And, like all cultures, the Basques have created some of their own unique musical instruments while incorporating others like the accordion that has since become a staple of Basque folk music. And others, like the txalaparta, almost disappeared only to see a revival in recent years. Yet others have been lost to time.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Please see the links in the main text.

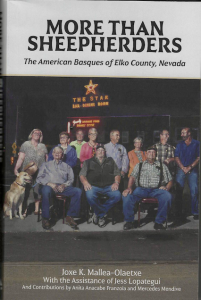

I recently interviewed Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe about his research studying the Basques of the American West, particularly the arboglyphs herders left on the aspens in the mountains. He is out with a new book focusing on the Basques of Nevada, specifically Elko. With assistance from Jess Lopategui, this book explores the role Basque immigrants had in the area, from the first to arrive in the 1870s to those that continue to define the region.

More Than Sheepherders: The American Basques of Elko County, Nevada

Joxe K. Mallea-Olaetxe with the assistance of Jess Lopategui

(from the University of Nevada Press)

In the remote community of Elko, Nevada, the Altube brothers and the Garats started fabled ranches in the early 1870s. These hardy citizens created the foundation of a community that still exists today, rooted in the traditions and cultures of American Basque families. Joxe K. Mallea-Olaetxe presents a modern study focused on the post-1970s, when the retired Basque sheepherders and their families became the dominant Americanized minority in the area. During this time, the Fourth of July National Basque Festival began to attract thousands of visitors from as far away as Europe to the small Nevada community and brought to light the vibrant customs of these Nevadans.

This book explores the American Basques’ present-day place in the West, bolstered by the collaborative efforts of four contributors, including two women—all who have been residents of Elko. The writers offer firsthand knowledge of their heritage through numerous vignettes, and these deeply personal perspectives will entice readers into Mallea-Olaetxe’s singular and entertaining historical account.

“Many Basque American communities are in need of a local history. For Elko, Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe fills this gap. He provides an in-depth history that focuses on early Basque immigrants in the sheep industry, while also highlighting their later work in restaurants, mining, and construction. The personal vignettes he includes allow the reader to meet the locals. Mallea-Olaetxe’s account details the experience of the Elko Basque community and provides a case study for deeper understanding of the Basque American Diaspora.”

—John Bieter, professor of history, Boise State University,

author of An Enduring Legacy: The Story of Basques in Idaho

AUTHOR/EDITOR BIOGRAPHY

Joxe K. Mallea-Olaetxe arrived in the United States from the Basque Country in the mid-1960s. He earned his PhD from the University of Nevada, Reno, in 1988. Mallea-Olaetxe is the author of Speaking Through the Aspens: Basque Tree Carvings in California and Nevada. He taught history and language classes at both UNR and Truckee Meadows Community College.

Jess Lopategui immigrated to Elko in 1957 and herded sheep from 1958 to 1965. He served as president of the Basque Club and, with his wife Denise and father-in-law Frank Arregui, was co-owner of the Elko Blacksmith Shop. After his retirement in 2006, he became more involved in researching the history of the Basques in Elko County.

Aditzaile onari, hitz gutxi.

A good listener needs few words.

.

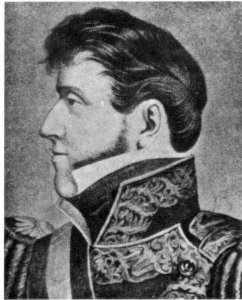

Growing up in Idaho, I of course learned about the Basque presence in the western United States and their role as sheepherders. But I didn’t realize the impact that Basques had had across other parts of the Americas. This is particularly true in Mexico, where as I’ve written Basques founded important cities. Basques continued to play an important part of the history of Mexico, and a prime example is the first Emperor of Mexico.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Agustín de Iturbide, Wikipedia; Asarta Epenza, Urbano. Iturbide Aramburu, Agustín. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/iturbide-aramburu-agustin/ar-71008/

Aditu nahi ez duenak, ez du esan behar.

He who doesn’t want to hear unpleasant things shouldn’t say unpleasant things.

.

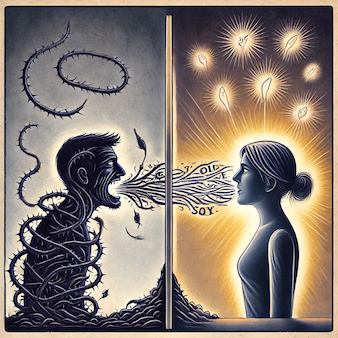

It seems like a simple question: what is the Basque word for God? But, like almost everything Basque, there is a lot of nuance in this simple question. The modern words for god and God in Basque are not typical Basque words. Does that mean they were borrowed? Or created by a priest only semi-literate in Basque? Or do they come from a more ancient source, the pre-Christian religion of the Basques? We’ll likely never know for sure, but this “simple” word carries a lot of history with it.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Some Important Basque Words (And a Bit of Culture) by Larry Trask, Buber’s Basque Page

Did you know that there are multiple ways you can follow Buber’s Basque Page?

Never miss a post!

Would you like your Basque club or town to be the “home” of the National (U.S.) Basque WWII Veterans Memorial?

The North American Basque Organizations’ (N.A.B.O.) Basques in World War II Special Committee has opened a call for proposals among its member clubs to host the future memorial intended to permanently remember and honor our Basque WWII veterans. The submission deadline is May 30, 2025.

Our mission is to honor the valor, sacrifice, and enduring legacy of Basque WWII veterans recognizing their profound contributions to freedom and democracy. Through commemorations, education, and advocacy, we pledge to ensure their stories are remembered, their sacrifices acknowledged, and their courage celebrated for generations to come.

As of today, the not-for profit historical association Sancho de Beurko Association has been able to identify over 1,900 WWII veterans of Basque origin (spanning three generations) in the U.S. Armed Forces, compiling research in 46 States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico, and the completion of 1,200 biographies. The identified 1,900 veterans resided in 30 States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico at the time of their enlistment.

As soon as the research is completed, the Sancho de Beurko Association would be pleased to donate and hand over the names of all identified Basque WWII veterans to N.A.B.O. as the main institutional representative of the Basque American community with the goal of creating a memorial. Consequently, no family will have to pay to have the names of their veterans engraved on the memorial.

The above image is just a simulation of a possible memorial plaza for our veterans. The memorial would consist of a physical site, displaying the names of all identified veterans of Basque ancestry who have served in every branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, including the Merchant Marines. (Needless to say, like any other memorial, ours will also have space for additional names as they are identified.) It would also be a place of public reflection and remembrance. The memorial would attempt to bring awareness and public recognition of the historical contribution made by a small immigrant community such as the Basques during WWII.

The memorial roster is Not Just a list of Names! It will be a permanent testament to their lives, families’ histories, sacrifices, and contributions to the U.S. The memorial would provide an opportunity to bring together all Basques from different communities across the country in the endeavor of commemorating the ‘greatest generation’ of Basque origin. In other words, it would promote social cohesion with a strong intergenerational component. In addition, the physical site would be complemented with a digital memorial site to access the veterans’ personal and military biographies.

The memorial is intended to preserve the memory of all veterans of Basque origin who served in the U.S. military in WWII and to serve as an educational tool for all who visit to learn of their sacrifices and unselfish contributions to this country.

Considering the size and the migration pattern of the Basques, this could be one of the first war memorial sites of its kind in the country. We believe that the National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial would become a national symbol of public recognition and pride comparable to the Basque Sheepherder Monument at Rancho San Rafael, in Reno, Nevada.

In summary, the memorial is the vehicle that embodies our mission. We have the duty to tell the story of these soldiers and preserve their memory. We must ensure the history of our veterans is never forgotten. For that we need your help. Would you like your club or town to be the “home” of the National Basque WWII Veterans Memorial?

As we are approaching the end of the research phase, we have started working on a set of criteria to select the best “home” for the physical memorial. Our idea is to inaugurate the memorial by the end of 2026, which marks the 85th anniversary of the United States entering WWII and the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States. A great context for the American society at large to learn about the contributions made by the Basques during the times of war and peace.

SELECTION PROCESS

All candidates wishing to bid for the memorial should present a brief plan, addressing the following criteria, in time and form.

What’s in it for the potential bidders?

Criteria

The criteria items are ranked as “Required” (meaning essential criteria) and “Desired” (meaning an extra bonus criteria):

SELECTION COMMITTEE

N.A.B.O.’s Basques in World War II Special Committee.

TIMELINE

Please do not hesitate to contact Marie Berterretche Petracek, Chair of the N.A.B.O.’s Basques in World War II Special Committee, at treasurer@nabasque.eus, if you have any questions.

“Let no veteran be forgotten—Ez ditzagun beteranoak ahaztu.”

Adiskidegabeko bizitza, auzogabeko heriotza.

A life without friends, means death without company.