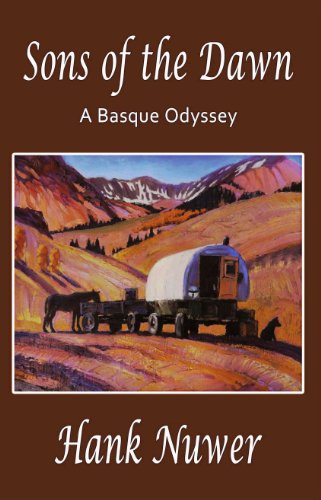

A long while back, I posted an announcement about Hank Nuwer’s novel Sons of the Dawn. He sent me a review of his novel by the writer David Allspaw which, much to my embarrassment, I never got to sharing. My apologies Hank. And I really, really need to read your book!

Sons of the Dawn Review

By David Allspaw

I have never traveled to Idaho. My familiarity of the state extends only to its rolling foothills and famous potatoes, which I hear are delicious. I do not doubt that it is a gem of the American West (as the nickname implies), but I know no more about its defining characteristics than I do about a distant country such as Luxembourg. For Midwestern folks like me, Idaho might as well reside in that Mountie-controlled territory to the North.

Nor am I any more aware of the nuances of Spain and its native language. I learned German in high school, which is about as far apart from Spanish as the entire span of the Pyrenees. The people of Spain were never anything more to me than foreigners residing in an unfamiliar region. The Spaniards’ idea of a national sporting event, I determined, is running from bulls in absurd outfits. They cannot be trusted.

With these thoughts in mind, I began reading Sons of the Dawn with the expectation that it would be a tedious and unsatisfying experience. I would not even want to attempt to herd sheep myself in the rugged terrain and climate of Idaho, and I definitely did not want to read about some fictional character doing it. My embarrassingly-limited knowledge of outdoors survival is a subject of frequent teasing by some of my friends, and it seemed that this story was about as relevant for me as a cookbook. I was clenching my teeth and preparing for the expansive boredom to come.

But it never arrived. In fact, I can honestly say that this book was one of the most rewarding and illuminating reads that I have ever stumbled upon. It was superb.

The novel begins with an origin story that seems to have come straight out of Harry Potter. A Spanish priest and his brother are hiking in the Pyrenees when an avalanche strikes below them, taking down a family caught in its path. When the men arrive, they discover that two young boys, Anton and Nicky Ibarra, have survived in the air pockets created by their mother’s coat. They are now orphans, and the priest assumes his seemingly God-granted duty of serving as the boys’ new guardian. You can probably guess that these brothers are destined for something great, considering that they have only faint memories of their dead parents, inexplicably lived through a deadly event, and were raised by an unassuming, caring elder. The story is not exactly original, but it serves to foreshadow the brothers’ ascent to hero-like status.

Soon enough, Anton and Nicky are shipped off to their uncle’s ranch in Idaho to pursue lives as sheepherders. While they chase the salary promised to them at the end of their herding obligation and the opportunity for owning land, they must contend with the brutal Idaho elements and the rancher thugs that attempt to kick them out of the territory. After all, a war is on with the brothers’ native country of Spain, and these “black Bascos” are viewed as threats to the unbridled power of Uncle Sam.

While Anton and Nicky’s adventures are entertaining, it is the deeply-authentic historical setting in which they take place that makes them believable. The author’s penchant for integrating historical nuggets and events into the storyline is similar to how Spielberg set the Indiana Jones movies amidst the emergence of World War II, but Sons of the Dawn contains more substance and realism than a film ever could. The history lessons here are much more intimate than the ones provided by a generic textbook, and I like them that way. When you read about the Spanish soldiers scouring Guernica for young fighters and capturing two of the brothers’ best friends, you gain a profound perspective of what it was like to fight conscription in a war-consumed country. Nuwer does not simply teach you the history of that time; he lets you live it through these characters. And that approach could only have been so effective through the immense amount of firsthand experience and on-site research that the author brought to the story.

In addition to the appeal to history buffs like me, the trials of sheepherding in a bygone era make this a memorable and absorbing read throughout. Anton and Nicky may only be young boys, but they are tasked with the challenge of herding sheep through the rugged terrain and climate of Idaho without much initial training in the craft. The brothers essentially arrive at the ranch, choose an eager young pup to serve as their aide, and head off into the unknown. They receive food every few weeks from Tubal, the head ranch assistant, and are otherwise solely responsible for their own survival and the health of the sheep. I cannot remember exactly what I was doing as a teenager, but I know that it was not even one-twentieth as arduous as the obstacles that these brothers have to overcome. The boys make some costly mistakes along the way, and it is fascinating to read how Tubal dissects their errors and teaches them the proper techniques of herding. Nicky and Anton’s maturation from young boys in their housekeeper and foster father’s care to seasoned ranchers is a crucial piece of the novel, and we as readers are able to take the journey with them.

Of course, life alone in the Idaho wilderness would be unbearable without some humor mixed in. The teasing and jokes from the brothers and Tubal are to be expected, but I think Nuwer overuses them throughout the book. At some points, it seems as if the characters are rodeo clowns rather than serious sheepherders. The capacity for the brothers to remain jovial after enduring so many hardships seems exaggerated, and it undermines the gritty realism that defines the story throughout.

Sons of the Dawn is precisely the kind of creative, historical fiction that my collection of literature has been lacking. The story serves as a refreshing alternative to the Game of Thrones and Fifty Shades of Grey-inspired novels that litter the shelves of libraries and bookstores, as it is not dumbed-down or profane. This is epic literature at its finest, and Nuwer’s cinematic style of writing brings to mind some of the great Western movies of the past. The book could make a great film, but I am afraid that Hollywood’s commercial-driven mindset would cause it to be less like Shane and more like Blazing Saddles. That kind of treatment would be unjust for a story so masterfully written.

Ultimately, the novel serves as an entertaining insight into the histories of the U.S., Idaho, and Spain. It provides an intimate look into the Basque identity, a group who is proud of its ancient tongue (according to the text, the Basque language is one of the oldest in the world and is thought to have existed since the Stone Age) and who desires independence from its Spanish counterparts. The novel’s depiction of the discrimination faced by Chinese and Basque immigrants is striking, and it teaches us that blacks were not the only group who faced social resistance in the U.S. If anything else, the frequent imagery of Idaho’s gorgeous scenery makes me want to travel there and see it for myself.

And maybe eat a few potatoes too.