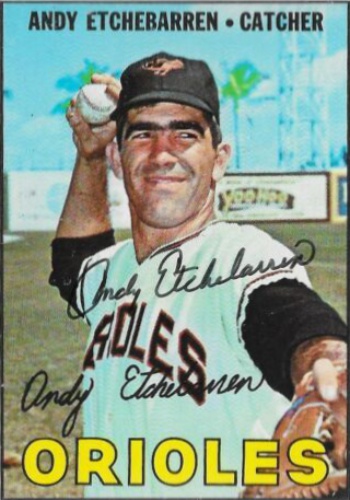

Andy Etchebarren was an All-Star catcher for the Baltimore Orioles, a fixture in their line-up from 1965-1975. While his offensive stats were not overly impressive, he was known for his toughness and his defensive skills. He appeared in four World Series, with his team winning twice. Etchebarren had the distinction of being the last player ever to face Sandy Koufax in a game, in Game Two of the 1966 World Series, in his rookie year. Etchebarren died on October 5, 2019.

- Etchebarren, the son of a French mother and a Basque-American father, was an All-Star twice, in his first two seasons in the major leagues. His career was plagued with injuries that constantly nagged at him and, after a few years, meant he was sharing catching duties with other players. Eventually, his diminished role led him to demand a trade and he was sent, in 1975, to the then California Angels.

- Etchebarren was a contender for Rookie of the Year during his 1965-1966 campaign. However, injuries side-lined him and he fell out of contention. He was also, at one time, a contender for MVP, in the end landing in 17th place in the voting. That year’s winner, Frank Robinson, also an Oriole, had fallen into a swimming pool at a party earlier that season. Robinson, not knowing how to swim, started sinking to the bottom. It was Etchebarren who dove in and saved his teammate.

- Regarding injuries, one story describes how, during a game, a foul tip hit his hand. The first baseman came to see if he was ok. Etchebarren brushed him off, saying he was fine, though a bone was visibly sticking out of his hand. He shoved it back in and continued playing.

- Of course, Etchebarren isn’t the only MLB player with Basque roots. Perhaps the most famous was Ted Williams, though his Basque roots were never very conspicuous.

- After his playing career was over, Etchebarren became a baseball manager, coaching at various levels. I guess he was known for his antics. In this clip, he is seen taking away a base after being ejected from the game.

Primary sources: Society for American Baseball Research; Wikipedia. Inspired by a post on Facebook by Xabier Berrueta.