One of the great pleasures of running this site is the opportunity it affords me to meet new people. And such was the case with Jesus Lizaso, a sculptor from Basauri, who was coming to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to discuss showing his work in a local gallery. Jesus doesn’t speak much English and, travelling to a far-off land, was hoping to find someone to connect to locally, someone who might serve as a touchstone to something familiar. Having found on the Internet that there is a Basque Club in Santa Fe, he contacted me about visiting our Etxea. Well, we don’t have an actual building, but I arranged to meet Jesus for dinner. And it was a great evening.

One of the great pleasures of running this site is the opportunity it affords me to meet new people. And such was the case with Jesus Lizaso, a sculptor from Basauri, who was coming to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to discuss showing his work in a local gallery. Jesus doesn’t speak much English and, travelling to a far-off land, was hoping to find someone to connect to locally, someone who might serve as a touchstone to something familiar. Having found on the Internet that there is a Basque Club in Santa Fe, he contacted me about visiting our Etxea. Well, we don’t have an actual building, but I arranged to meet Jesus for dinner. And it was a great evening.

Jesus’ livelihood is art and it is a livelihood fraught with uncertainty. Each piece takes him hours and hours to fabricate, and he is good at his craft, having won prestigious prizes. Even so, he only sells a handful of pieces a year, so each sale is crucial and precious. Jesus was visiting the US to broker an arrangement with a local gallery in Santa Fe to show his work and act as his agent in the US.

Probably the most fascinating aspect of the evening was just learning more about how the art world works, including the role that galleries play in the process of selling and distributing art, and how difficult it is even for an artist who has been by all accounts very successful to still make a living at making art. We had dinner at a local tapas restaurant and it was also entertaining to hear the reaction of a Basque to the food being served. One comment that stuck with me was how Americans always need to make their food so spicy. Which was a bit funny, since at least one of the dishes involved chorizo from Spain that was probably the spiciest item we had that evening.

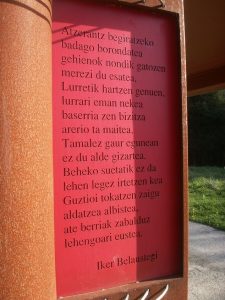

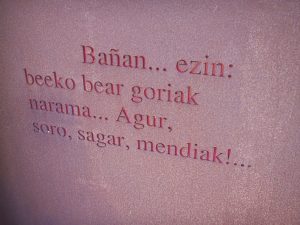

Jesus calls his work “solid poems”. And, judging by the photos on his website, they are indeed poetic. Typically of stone or wood, and often of very large size (he described to me the difficulty of moving his work internationally; the cost alone is significant), his works are often inspired by industry, involving gears, nails and screws. This type of sculpture really appeals to me, with the angular design and the abstract forms. Some day…

Jesus calls his work “solid poems”. And, judging by the photos on his website, they are indeed poetic. Typically of stone or wood, and often of very large size (he described to me the difficulty of moving his work internationally; the cost alone is significant), his works are often inspired by industry, involving gears, nails and screws. This type of sculpture really appeals to me, with the angular design and the abstract forms. Some day…

For those that speak Spanish, this video offers a bit of Jesus’ perspective on the creative process.