Basques looking for opportunity traveled throughout the world. Many landed in the Americas but more than a few made their way to Australia, encourage by informal government initiatives between Spain and Australia to work in the sugarcane fields. But these lonely men desired companionship, so a second plan was hatched to bring “young, attractive, and single” women to the continent. Though it was a hard and lonely life, many of these Basques established a new community in this far-away land.

- Basques, typically from Hegoalde rather than Iparralde, first arrived in Australia in maybe the 1910s. There is a story that some merchants from Lekeitio abandoned their ship in Sydney to work in the lucrative sugarcane industry. However they first got there, some Basques saved and bought their own sugarcane properties. These Basques would sponsor family members to come to Australia and this was the nucleus of the Basque-Australian community.

- However, after the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II, Basque immigration to Australia essentially stopped. The sugarcane industry took a hit as there was no new labor force arriving for the hard work of working in the fields. To help recruit new Basques to the area, people like Alberto Urberuaga were sent back to their native lands to find more Basques to come to Australia.

- In informal agreements with the Spanish government (at the time, Australia and Spain didn’t have formal diplomatic ties), Basques and other Spanish citizens were recruited to Australia. The first group that came as part of Operation Kangaroo arrived in Brisbane, Queensland, aboard the SS Toscana, on August 9, 1958. In total, these “operations” – Emu, Eucalyptus, and Kangaroo – brought some 700 men from northern Spain to northern Queensland as sugarcane cutters.

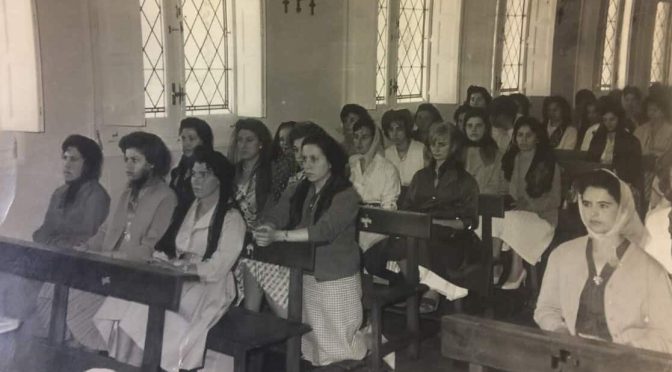

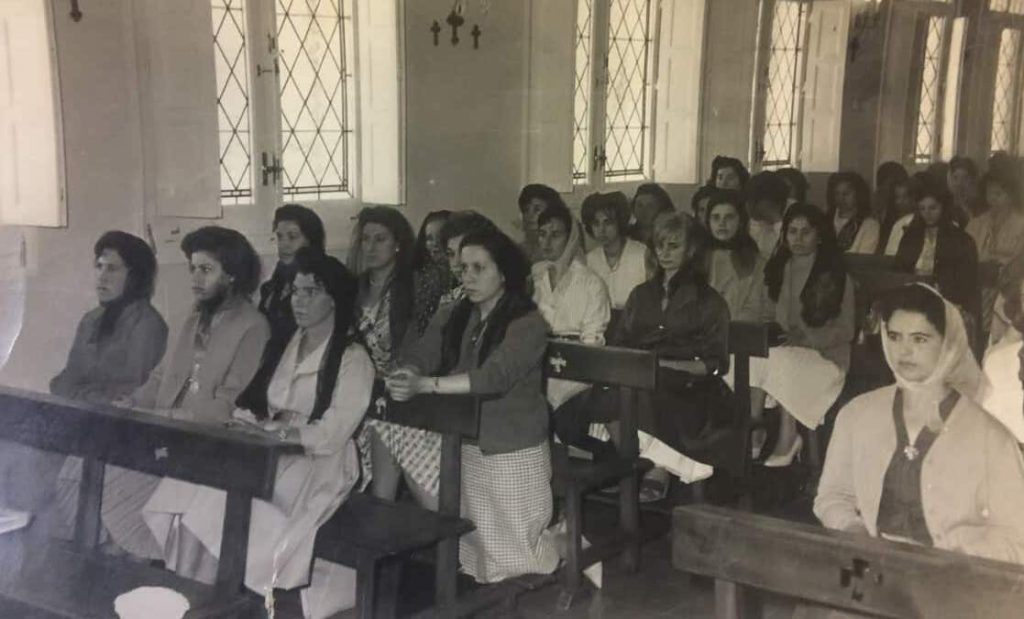

- There was then a concern that these men, mostly single, were lonely and even suicidal. Thus, a second agreement was arranged between Australia and Spain to bring single women. Plan Martha, or Operation Martha, brought 7 groups of women to Australia. The first contingent of 18 women arrived on March 10, 1960, on what became known as the “brides’ plane.” Between 1960 and 1963, about 300 (one source says 700) young women immigrated to Australia through Plan Martha. While told they were coming to work as domestic servants, the real goal was to balance the genders in the Basque/Spanish population – they were selected on the criteria of being “young, attractive and single.” The women were met by crowds of young Basque and Spanish men looking for a bride. Many felt they had been deceived, promised a land of opportunity but finding a backwards place where they couldn’t even go out for a coffee.

- These women were at the heart of a local scandal. There were news reports that some of the women were working at a vineyard, picking grapes in the nude to escape the heat. While the story was debunked, it rose to enough of a story that the Consul-General for Spain in Australia was brought in to investigate.

- From these beginnings in the sugarcane fields, Basques spread to other parts of Australia and other parts of the Australian economy. They formed clubs in both Melbourne and Sydney.

Primary sources: Douglass, William Anthony. Vascos en Australia. Auñamendi Encyclopedia. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/vascos-en-australia/ar-150184/; Plan Martha, Wikipedia; Operation Kangaroo, Wikipedia; ‘The flight of the brides’: 60 years on from the one-way ticket from Spain that changed Australian migration, SBS