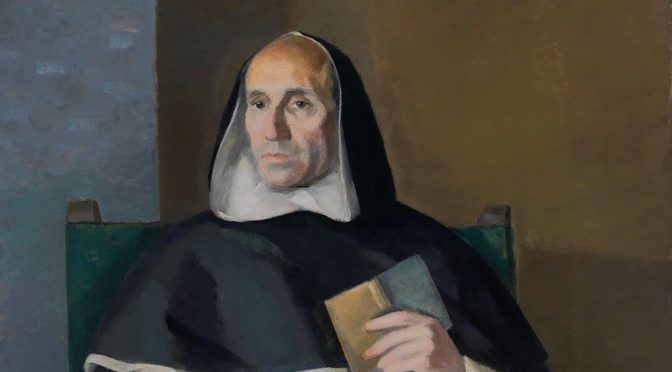

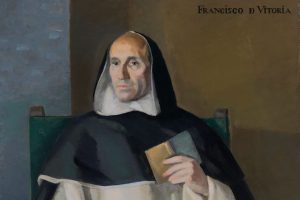

It’s somewhat amazing to realize that we can get a reasonable forecast of the weather by simply looking at our phones. Granted, they aren’t perfect – forecasting the weather is extremely hard – but overall, when meteorologists say there is a 50% chance of snow, half the time it snows on those days. It wasn’t that long ago however where we were at the mercy of the weather, hoping that wizards and witches could prevent storms from destroying crops. One of the first to apply a scientific approach to the weather was Juan Migel Okrolaga, a priest from Gipuzkoa.

- Juan Migel Orkolaga Legarra was born in Hernani, Gipuzkoa on October 1, 1863. He was a sickly child who was rather introverted compared to his peers. Instead of playing with toys and the like, he would watch and record the world around him, foreshadowing his future career path. In a futile effort to improve his health, he moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina as a young man, but returned to the Basque Country in the 1880s.

- It was in Buenos Aires where he began his studies for the priesthood, to become a Jesuit, which he continued in the Seminary of Vitoria upon his return. Once he completed his vows in 1888, he was first assigned to the parish of Beizama before going to Zarautz.

- In Zarautz, he began his rigorous observations of the weather. He built his first observatory and made predictions about the coming weather. He predicted the gale of November 15, 1900, giving authorities enough advanced notice that many lives were saved.

- His successes led him to propose to the province the creation of a meteorological observatory. Built in Igeldo, Orkolaga was taking measurements by 1905. He predicted the storm of August 14, 1912, which again helped save the lives of many fishermen in the province. In contrast, in Bizkaia where his predictions were not available (Bizkaia had pulled out of helping fund the observatory due to a disagreement on its location), 143 fishermen died.

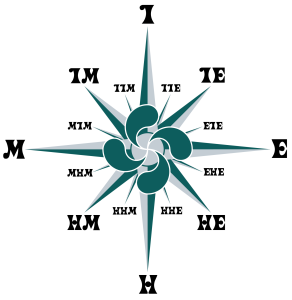

- Orkolaga was self taught, and his lack of a scientific background caused some conflict with the scientific community. However, he had the knowledge and skills to construct a wide range of devices he used in his studies of the weather, including an anemo-cinemograph, a device used to measure wind speeds; an anemo-copograph, a device that indicates the direction of the wind by the hour; a rain gauge for fallen rain; another rain gauge which indicated the amount of water fallen and the direction of the wind; two hygrometers for relative humidity (one functioning as a heliograph, for the alternatives of sun and shade, and the other always remaining in the shade); and an anemoscope, which indicates the value of the periods of the prevailing winds for 12 or 24 hours.

- With these instruments he created what he called a scientific-intuitive approach to weather monitoring and forecasting, as opposed to the use of mathematical models. By knowing the state of the various parameters he measured, he could intuit the coming of storms. He also asserted that he only really needed the barometer, that things like temperature and humidity were “distractions” that really didn’t help with forecasting. However his biases would also lead him to ignore advances in dynamic meteorology and technology that further advanced the science of meteorology.

A full list of all of Buber’s Basque Facts of the Week can be found in the Archive.

Primary sources: Juan Migel Orkolaga, Wikipedia; Anduaga Egaña, Aitor. Orcolaga Legarra, Juan Miguel. Auñamendi Encyclopedia, 2023. Available at: https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/en/orcolaga-legarra-juan-miguel/ar-111214/